In 1838, American militia members evacuate Simu-quah, a young Potawatomi girl, and the rest of her family from their village at Twin Lakes in Indiana and force them to begin a long march to Kansas. Seeing her father, a local headman (or chief), chained in the back of a prison wagon, Simu-quah resolved to help him and her people escape their bonds and return to their ancestral home. Yet the challenges they face prove too much to overcome. The mandatory expedition eventually begins, and the young Potawatomi girl packs 13 ears of corn in her beaded birch bark-carrying pouch for the journey ahead.

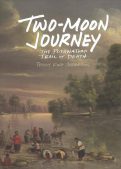

Author Peggy King Anderson chronicled the story of Simu-quah and their migration in her book Two-Moon Journey: The Potawatomi Trail of Death. By bringing to life a more personal account of what the first removal was like, Anderson aimed to change the lack of clear human connection with the Potawatomi marched at gunpoint from their homeland in this fictional account.

She used historical sources to give a first-person perspective of the Potawatomi removal amidst one of the worst droughts in the 1830s. The two-month trek – which lasted approximately two lunar cycles – crossed 660 miles spanning four present-day U.S. states and ended in Sugar Creek, Kansas.

Anderson’s husband, Ken, was a Citizen Potawatomi Nation tribal member. Shortly after they married, she and Ken regularly attended regional Tribal council meetings in Washington State for CPN members who lived in the area. Through these and other interactions, Anderson learned more about Potawatomi history and culture.

“Because I was encouraged over the years to do this book by Potawatomi members, and because my husband and children are all Potawatomi members, I didn’t feel the apprehension I would have otherwise,” Anderson said.

Anderson shaped the tale of what would become Two-Moon Journey in an earlier work for Highlights children’s magazine in 2002. In that non-fiction piece, Anderson described details of the removal using primary resources from the 19th century. Her familiarity with the subject, coupled with an encounter with CPN member Sister Virginia Pearl, helped put Two-Moon Journey on the path to creation.

Pearl’s great-grandmother, Equa-Ke-Sec, marched on the Trail of Death.

“Simu-quah is modeled after Equa-Ke-Sec, both in her courage and determination, as well as her experiences on the forced march, especially the ending scene when they arrive at Sugar Creek and find none of the promised homes, and have to hang animal skins from the stone banks of the creek for shelter from the cold,” Anderson said. “That one particular detail shared by Sister Virginia Pearl created an emotional image for me that catapulted me into writing this book.”

While chronicling the everyday events of the journey, Anderson’s work sought to address a question she often received when she read of the events surrounding the Trail of Death; how could it be possible to forgive such a horrible injustice?

Readers will have to do their own introspections after finishing Two-Moon Journey, though Anderson hopes Simu-quah’s story forges a connection with the Removal Era Potawatomi and their descendants today.

“This, more than anything, is what I wanted to convey in Two-Moon Journey: the courage not just of one girl, but of an entire people … so many years after their forced removal, (who) have regained their strength and now bring the lessons of that historical event to others, through the sharing of Potawatomi spiritual values and cultural traditions,” Anderson said.

Since the book’s release in spring 2018, Anderson has heard from Tribal members who have read it and received positive responses thus far.

Two-Moon Journey is appropriate for young adult readers but is enjoyable for readers of all ages. The book is available online at shop.indianahistory.org, Amazon and in person at the Citizen Potawatomi Gift Shop inside the CPN Cultural Heritage Center.