Approximately a mile southeast of Maple Hill, Kansas, along Mill Creek sits the remnants of influential Potawatomi Jude Bourassa’s gristmills.

Jude’s father, Daniel Bourassa II, was the first to sign the Muster Roll, which began the Potawatomi people’s forced removal from Indiana to present-day Kansas on the Trail of Death. However, Jude did not leave Indiana during the removal, writing to then President Martin Van Buren in an attempt to stay in the state. President Van Buren never replied, and Jude made his way to the new Potawatomi reserve west of the Missouri state line in 1840.

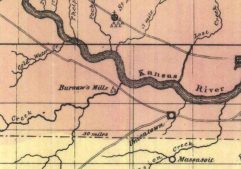

Three years following the Tribe’s relocation to the Pottawatomie Reserve on the Kansas River, the federal government helped Jude establish successful gristmills in 1850 on Mill Creek, a Kansas River tributary, near Uniontown and Plowboy settlements.

Before electricity, water sources often provided energy to power machines. A gristmill like Jude’s used the river’s energy to rotate large stones which processed grains like corn, wheat and rye.

“It’s how they got their ground corn, our flour — anything that went through a gristmill, primarily came from Jude’s mills,” said Jon Boursaw, Citizen Potawatomi Nation District 4 legislator and Daniel Bourassa II descendant.

Mysterious treasure

Jude’s enterprise also included a boarding house. Kansas’ first Territorial Governor William H. Hutter wrote a letter about an intriguing item during his stay at Jude’s in 1854, which may link the Potawatomi to the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.

“He has four slips of parchment covered with Hebrew manuscript, which he has sent to Washington and had translated and which prove to be extracts from the 13th chapter of Exodus and 6th chapter of Deuteronomy, and relate principally to the Passover,” Hutter said in his letter.

Jude procured the artifacts from a chief whose family secretly kept them for generations.

“Mr. B. says there is very good evidence of the tribe having had them for 200 or 250 years, and the tradition accompanying them is that the Red men brought them along with them into this Island, as they call the Continent, and that some day they were to be called for,” Hutter wrote.

“They are rolled in small flat rolls, and inserted in a stiff, hard box about 2 inches each way, the outsides of which are made of repeated thicknesses of parchment, closely and solidly compressed together and blacked outside with considerable polish. On each end is an ornament consisting of three or four long stalks, each having a bulb at the end, which may represent fruit or flower. — This box has four compartments one for each of the rolls. Around the open top of the box a square rim projects of about half-inch, and the same piece of parchment (double) which makes this rim, folds over and makes a cover, and this was closely and solidly sewed down, and the outside finished like the body of the box — so that it was impervious to air or water,” he said.

Oral tradition indicates the Potawatomi once had two of these boxes, but during a migration, a box went missing after a canoe tipped.

“All recollection of the time and place is lost. It is impossible they could have got these things from the Missionaries, for at 200 or 250 years ago none were among them, and if they were they would have no reason for giving these remembrances of the Passover to the Indians,” Hutter said. “Besides the earliest Missionaries they did meet were Catholics, and it is a well known fact that all their amulets are in Latin, and of a different character from that of these extracts. Again Mr. B. tells me that this particular kind of box for the preservation of texts of Scripture, has been, and is in use among the Jews, and that a Jew who saw it in his possession recognized it at once as a Jewish box.”

Jon’s brother Lyman Boursaw said, “It’s possible that the Knights Templar brought artifacts over in an attempt to provide protection from outside invasions. Some believe the Knights Templar buried the artifacts on Oak Island,” which is in present-day Nova Scotia, Canada.

Bourassa family rumor has it Jude sent the artifacts to Washington D.C. for authentication. What happened to the scrolls since is unknown, Lyman said.

Time in Kansas

Before moving to present-day Kansas, Jude received his education from the Carey Mission near Niles, Michigan, and the Baptist Theological Institute at Hamilton, New York, now Colgate University.

Once arriving at the reservation, Jude initially settled near Sugar Creek. After a disagreement with the Jesuits there, he relocated to Pottawatomie Creek to live near the Baptists, including Robert Simerwell and Johnston Lykins.

He made a comfortable house near Uniontown, and a newspaper correspondent Charles B. Lines recorded on April 26, 1856, that Jude’s quarters were some of the best in the territory. Lines also highlighted, “While Mr. Bourassa is very attentive to his guests and liberal in his charges, he will furnish no whiskey under any circumstances.”

Jude continued milling and serving as an innkeeper before he passed away from smallpox in the mid to late 1850s. Following his death, the gristmills became inoperable after a flood. This prompted another Potawatomi named Louis Vieux to open a gristmill in 1858 near Louisville, Kansas. Very little remains today of what was once a busy enterprise. Jude’s children eventually took allotments in Oklahoma, and his land in Kansas is now under private ownership.