March 26, 2022, is Epilepsy Awareness Day, and more than 51,000 Indigenous people live with the disorder in the United States, according to the Epilepsy Foundation of America. Epilepsy affects more than 3.4 million Americans, as reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, making it the fourth most common neurological disorder.

Citizen Potawatomi Nation Health Services Primary Care Physician Dr. Patrick Kennedye treats and guides patients as part of their team of doctors. He also assists the inpatient psychiatric hospital at INTEGRIS Mental Health Spencer in Spencer, Oklahoma.

“A lot of these patients have ADHD and autism, and they have associated increased rates of seizures, so I am frequently consulted to figure out if we need to send patients to the pediatric neurologist,” Dr. Kennedye said.

Much of the care surrounding seizures focuses on education, prevention and safety.

CPN tribal member and Nadeau family descendant Pam Vrooman experienced her first seizure at 24 years old. In her 60s, her routines and proactive measures help her lead the life she wants.

“I meditate, I work out, I garden. I take baths, and I hot tub. I have these little rituals around drinking tea. Those are really critical for me. They keep me on a fairly even keel,” Vrooman said.

Diagnosis

Epilepsy is a neurological condition characterized by abnormal brain activity resulting in recurring seizures. The World Health Organization calls it “one of the world’s oldest recognized conditions, with written records dating back to 4,000 BC.” The broad definition of epilepsy encompasses many types of seizures and responses of each patient.

Dr. Kennedye explained in a recent Hownikan interview how a change in blood flow to the brain affects the body’s ability to regulate itself, especially with age.

“Epilepsy is oftentimes triggered in these states where you have low energy because the parts that are restricting and inhibiting those problems are no longer working, which then allows unregulated electrical activity through the brain,” he said.

The American Association of Neurological Surgeons classifies seizures into two broad types — generalized onset or focal onset, meaning abnormal activity is either widespread across the brain or in one limited area. Each individual’s episodes look different physically, some resulting in convulsions and spasms, and others in blank stares and lip smacking.

“People typically think of seizures as the generalized tonic-clonic seizures that you see in movies, which don’t even look like real seizures. The depictions in movies often look like psychogenic, non-epileptic seizures. Because … it’s hard to fake,” Dr. Kennedye said.

Vrooman mostly experiences tonic-clonic seizures, although they present themselves differently from what others imagine.

“Sometimes, I will seize up and be stiff as a board, and people can’t even bend my limbs. And … I have to take people’s word on it since I’m not really around (mentally). But I have them enough that they scare people for sure,” she said.

While the condition occurs at any age, epilepsy most affects children and those over 65.

Safety

When talking with or referring a patient to a neurologist for further care, Dr. Kennedye focuses on safety during seizures. Some of his tips include not bathing or swimming without supervision for the risk of drowning, and laying someone on their side to avoid aspirating after vomiting. He advises patients’ friends and family members against sticking anything in the mouth during a seizure. For patients 16 and older, restricted driving also presents issues.

“That’s a huge one. And oftentimes if I suspect an epilepsy disorder, and I think that there might be recurrent seizures, then I have to restrict their driving until they are cleared by the neurologist. … A typical requirement is to be seizure-free for six months before people can start driving again, which can be very disruptive to people’s schedules,” Dr. Kennedye said; however, state laws differ.

Vrooman lays on the floor if she feels one coming on and alerts anyone around her.

“If I think I’m going to have one in my office, I have a whistle that I keep around me that’s loud enough that anyone, any of my coworkers, could hear me to just come check,” she said.

Dr. Kennedye also discusses with his patients what constitutes an epileptic emergency. While calling an ambulance during every seizure seems intuitive, often they end before EMTs arrive.

“Typically, if you’re having seizures lasting over five minutes, that’s a big one, or ones that are unresponsive to antiepileptic drugs in the moment, like benzodiazepines. … Knowing when to call 911 and when not to call 911. There’s a lot of education that goes (into it). When someone gets diagnosed with epilepsy, they have to figure that out,” he said.

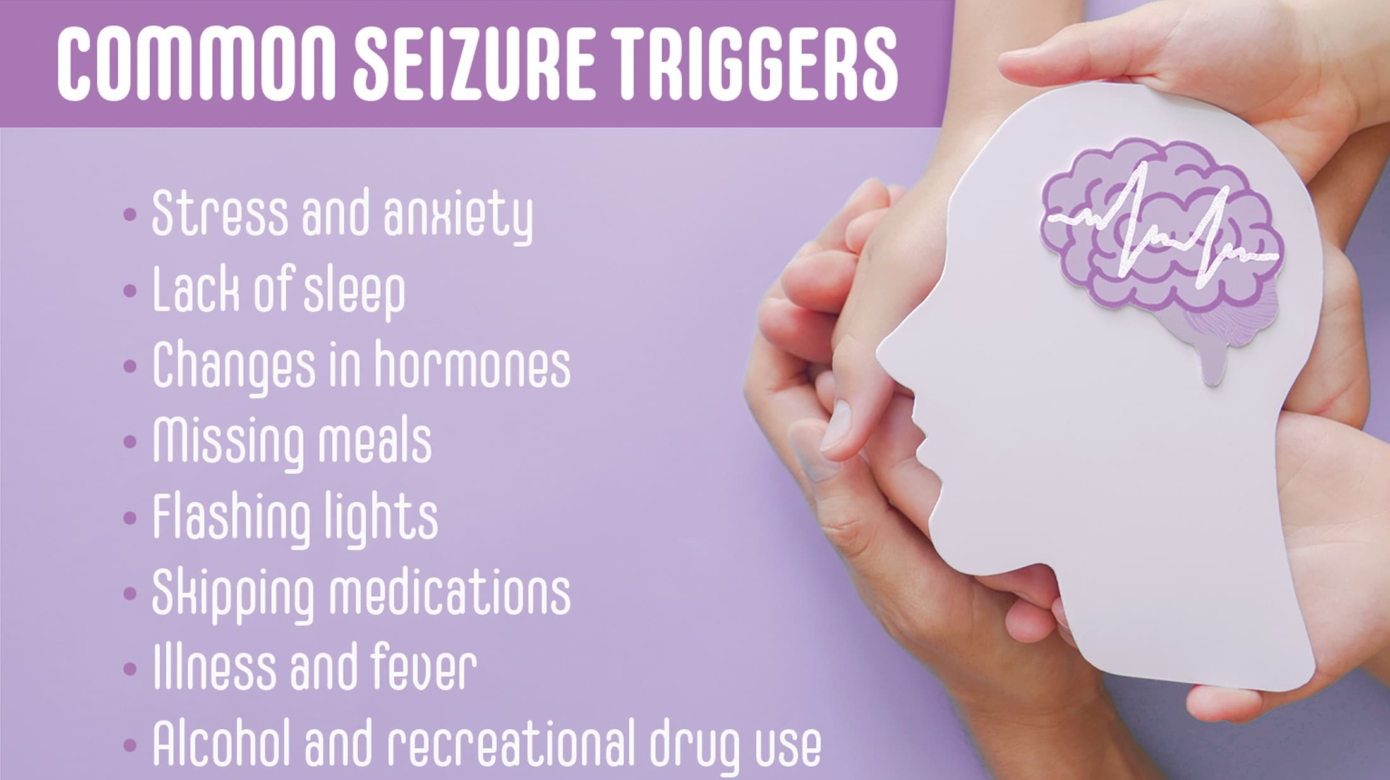

Common triggers include lack of sleep, stress and anxiety, hormonal changes, flashing lights, skipping medications, and changes in blood sugar.

“I don’t really eat a lot of fast food or processed foods anymore, so I drink a lot more water. I just really looked at general health stuff, and I’m trying to take that a lot more seriously. But sleep was the main (trigger) for me,” Vrooman said.

Treatment

Maintaining a medication schedule often makes a difference in preventing breakthrough seizures. Dr. Kennedye talks to his patients about the importance of keeping in touch with their neurologist to adjust or change medications.

Logging seizures and their frequency, length and possible triggers provide more information to help health care providers better determine treatment and track progress.

“Charting exactly when do they happen? Are there certain times of day that they happen? Are there triggers that you might associate with epilepsy? Are there certain foods that make it worse? Some people have issues with flashing lights that can trigger epileptic seizures, and nutrition is another really big one that can play a big role as well,” Dr. Kennedye said.

He often presents maintaining a ketogenic diet as a treatment possibility, consisting of animal-based, high-fat, low-carbohydrate foods. It was initially created in the 1920s prior to the availability of antiepileptic medications.

“That was before we had really fairly effective medications, and with certain types of epilepsy (the keto diet) can be pretty effective,” said Dr. Kennedye. “And I think there’s lots of other benefits besides that. And so that’s something I’ve been recommending for my patients.”

Besides diets and medicines, neurologists sometimes recommend implants for their patients to help regulate their brain activity, including the vagus nerve stimulator. As one of the primary nerves through the body, the vagus nerve assists in the control of the heart, lungs and digestive tract.

With advancements in treatment and the understanding of the brain, doctors have more resources at their disposal than ever before to help epileptic patients live full, unrestricted lives.

Learn more about epilepsy from The Epilepsy Foundation at epilepsy.com. Check out Citizen Potawatomi Nation Health Services at cpn.news/health.