Those who have been convicted of felony offenses often face challenges in moving on with their lives after they have served their time. Many ex-felons face systemic obstacles to housing, transportation and employment after their convictions, resulting in a recidivism rate that stretches criminal justice budgets at the state and local levels.

Those who have been convicted of felony offenses often face challenges in moving on with their lives after they have served their time. Many ex-felons face systemic obstacles to housing, transportation and employment after their convictions, resulting in a recidivism rate that stretches criminal justice budgets at the state and local levels.

Burdened by a ballooning prisoner population and budget shortfalls resulting in widespread understaffing of the Oklahoma Department of Corrections, recent sessions of the Oklahoma Legislature have studied how to alleviate these issues. Thus far, impactful legislative action has not emerged from the statehouse despite the prison population being at 104 percent capacity. The closest the state has come to true reform was the 2011 House Bill 2131 by then-Shawnee, Oklahoma Speaker of the House Kris Steele. The legislation aimed to cut the incarceration rate by implementing concurrent sentencing and GPS monitoring while expanding eligibility for community sentencing.

However, after parts of the bill concerning the state pardon and parole board were deemed unconstitutional by Attorney General Scott Pruitt, a reform bill in the 2012 session called the Judicial Reinvestment Initiative was signed into law by Governor Mary Fallin.

Yet hopes for improvements were dashed as the governor’s office appeared to withdraw support for the law, with her office’s budget not including funding for the reforms.

The governor also rescinded federal grant funds to be used as part of the reforms, saying that the state would fund initiatives to raise awareness of new laws for attorneys, law enforcement and judges. That state funding never materialized though, as Speaker Steele told the Tulsa World in 2014, “They said we didn’t need it, we had enough money…Oklahoma could pay for its own program. Well, that’s never happened.”

Small steps

Former Speaker Steele, who has led renewed efforts to put criminal justice reform measures to a direct vote of the people since the JRI’s failure, told Oklahoma Watch that he believed the governor’s office balked in order to appear tough on crime and due to pressure from private prison groups.

The decisions that undermined the reforms also took place before the global oil price collapse of the past two years, and a once-booming Oklahoma economy has sputtered as of late. According to the state treasurer’s office, Oklahoma entered a recession sometime in mid-2015. Unemployment has crept up, while the past two legislative sessions have faced $611 million and $1.3 billion budget shortfalls, causing cuts to a wide range of state agencies and services. Though large scale solutions appear impossible despite the Republican Party controlling supermajorities in both chambers of the legislature as well as the governor’s office, incremental progress has been forthcoming.

In February 2016, Governor Fallin signed an executive order altering job applications for state agencies. The order removed questions asking about criminal history on the applications, known as “banning the box.” The order does not halt background checks or questions about past convictions asked during the interview process.

Tribes search for solutions

Like many issues impacting rural Oklahoma that can’t or won’t be met by the state, tribal nations have stepped up to find ways for Native American ex-felons to succeed once out of prison. The Oklahoma Inter-Tribal Reentry Alliance is one such entity, offering support, instruction, and education training to ex-offenders. Citizen Potawatomi Nation is one of the group’s founding members.

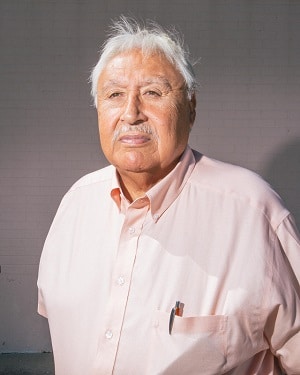

At CPN, one of the tribal reintegration program’s most visible and ardent advocates is Burt Patadal. A member of the Kiowa Nation, Patadal is a familiar face in Pottawatomie County, having been raised in Shawnee. He is Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s Tribal-Reentry Program coordinator for ex-felons in CPN’s Employment and Training Program.

He describes the contrasts he’s seen in convictions between the states, noting that some offenses in South Dakota will only result in a misdemeanor charge whereas in Oklahoma, the offender would be charged with a felony.

Patadal, who insists that those he works with attend some form of counseling, explained the circumstances facing ex-felons once they leave prison. Like everyone else, they have to pay rent, go to work, get a driver’s license and an automobile as well as repay court ordered fines and fees.

Yet even getting to where they can do those things is troublesome in Oklahoma. State law requires felons who lose their driver’s licenses because of their convictions to pay off their fines before it is reinstated, typically at a cost of around $3,500. Oklahoma’s public transportation infrastructure essentially serves the large metropolitan areas of Tulsa and Oklahoma City, leaving many rural dwelling ex-felons unable to get to their place of employment if it is a few miles from their home.

In Pottawatomie County, this situation is especially stark, with few public ride programs operating. Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s own transit program is free to the public, but is typically booked up weeks in advance since it operates by appointments only. Though case managers like Patadal try to secure bicycles for ex-felons they’re assisting, others may choose to either drive illegally or return to more illicit money making ventures to help pay the bills. Even those with valid transportation confront another set of trying circumstances.

“If they don’t have an education or any skills, they have to go get a job at a fast food restaurant, but then they’re only making $7.50 an hour,” explained Patadal. “How are you going to pay your rent, your utilities and then your restitution?”

Should they meet those challenges, Patadal noted that something as simple as a traffic violation can send an ex-offender back into the prison system.

“The thing is, you can have a person get out of prison that gets themselves a job, a wife, a house and is on the right path, and then they get pulled over for something as small as a speeding ticket. When that police officer runs the name, they just show an outstanding fine and have to lock the person up. If they can’t make bail, they stay in and then can lose their job.”

“It just seems like Oklahoma keeps kicking them, and kicking them and kicking them. You know, get over it man, they’ve done their five years, let them get along with their life,” he said.

Though there is no fix-all solution to these issues, the hope is that eventually, smarter sentencing and post-conviction restrictions will emerge. In a local example, one has.

The City of Shawnee Municipal Court has become a key partner in Patadal’s work through the CPN Tribal Reintegration Program. With four tribal nations in the city’s immediate vicinity and 14 percent of its population being Native American, Judge Randall Wiley has sought solutions to lower recidivism rates. “Elder Burt,” as Judge Wiley refers to him, has been so successful in helping Native Americans who’ve appeared before him that he appointed Patadal to a position in his Recovery Court.

“Elder Burt’s energy and experience has made him an invaluable member of my court team,” said Judge Wiley.

Progress made when it’s truly wanted

Brandon White had been fighting alcoholism for years, attending rehabilitation and detox programs while attempting to get sober. Each time he found his way back to his old habits, ending up at the bottom of a glass of 100 proof vodka. Even after an 11-month stint in prison where despite drying up, he felt he needed to be in some sort of a structured environment to help deal with his alcoholism. Speaking from his personal experience, simply being behind bars wasn’t a solution for someone struggling with addiction.

“All it did was make me angry because I felt like I needed to be in a place where they were going to help me better myself,” he explained. “When I got out, they threw me a $200 food stamp card and whatever I had saved in there. Then I came out, and I was already drinking my first day after being sober the whole time I was away.”

Patadal said that many just need to know someone is there for them.

“I always tell them, ‘If you want to do it, I’ll help you do it.’ If we want them (felons) off the streets, you’ve got to help them,” he said.

To White, he felt he’d been cast about with no support structure and little direction.

“I had no foundation, nothing to keep me going really,” said White. “When you’re a grown man, you think you can go out and walk the face of this world. But when you’re an alcoholic or you’re a druggie, you’ve got a whole different outlook on what you’re facing out there. It’ll tear you down, and it did me, several times.”

Falling under its jurisdiction due to his tribal heritage from the Kickapoo and Shawnee tribes, White was ordered by the CPN Tribal Court to take part in counseling sessions with Patadal. They were different from the Alcoholics Anonymous and alcohol rehabilitation classes he’d been a part of before. Patadal, a tribal elder and former member of the American Indian Movement, is an advocate of traditional Native American ceremonies like talking circles and sweat lodges. He hosts weekly versions of the former for Native ex-felons as they transition back to civilian life after prison. White soon became a regular at these gatherings, which he credits for his ongoing sobriety. Through an agreement with the courts, Patadal can count meeting attendance at these ceremonies that will deduct small court costs from their outstanding fines.

“I was tired of drinking and wanted to live a better life, I just didn’t know how to go about doing it,” White said. “I can talk all day about getting sober and how I’m going to do it while I’m in rehab getting three meals, but once I come out in the real world you know, it’s a different story. I needed someone to lean on. I needed a hand and Burt was the one who stepped up.”

In Oklahoma, there are two lists of professions that are either barred from hiring felons, or can fire those already working due to a past felony. Advocates for reform largely do not support opening all jobs to ex-felons. However, bans remain in effect for licenses in professions such as interior designers, embalmers and landscape architects. Those who do get hired for jobs like drug and alcohol counselors, clinical social workers or real estate sales can be fired simply for having a felony on their record, no matter how much time has passed since the crime was committed.

White’s previous experience working in the oil fields provided him a skill set that has allowed him to find work at a local tire shop whose owner knows Patadal and trusts his recommendations on potential employees.

Yet White explained that his previous convictions remain a blemish on his record that hampers his prospects, especially if non-felons apply for the same job.

“Automatically I’m branded ‘bad.’ It doesn’t even matter what that felony is for…you’re branded and they’re not going to look into what you did, unless they need help really bad.”

In order to be up front about his felony record, White would note on applications that asked that it was for a DUI.

“But DUI automatically meant, ‘hey he’s a drunk,’” said White.

While practical challenges like these perceptions remain, advocates like Patadal will continue to work towards solutions. He points to White as one of the success stories, an example he can cite to employers who trust his recommendation when considering hiring an ex-felon.

To learn more about the Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s Tribal Re-Integration Program, call 405-598-0797.