Amidst the economic and agricultural slump that hit the Great Plains in the 1920s – long preceding the Great Depression to follow the 1929 stock market crash – a new school of art was forming at the Bacone College in Muskogee, Oklahoma. The institution, formed to educate Native Americans from across the country

in the place once known as Indian Territory, became world famous for its Bacone School of Art.

Bacone was Oklahoma’s first college. In what was then-called the Indian College, classes began in Feb. 1880 in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. In 1910, the college received its contemporary name in honor of Almon C. Bacone, its first president and a longtime, vocal opponent of the U.S. government’s Indian Removal policies.

Its current location in Muskogee, Oklahoma sits on land donated by the Muscogee-Creek Nation. In the interest of increasing enrollment in the years after WWI, university President B.D. Weeks promoted Bacone as a learning institution exclusively aimed at Native American students. Weeks recruited Native American faculty, one of which was world-renowned Potawatomi artist Woody Crumbo, who led the Bacone School of Art from 1938-1941.

Its current location in Muskogee, Oklahoma sits on land donated by the Muscogee-Creek Nation. In the interest of increasing enrollment in the years after WWI, university President B.D. Weeks promoted Bacone as a learning institution exclusively aimed at Native American students. Weeks recruited Native American faculty, one of which was world-renowned Potawatomi artist Woody Crumbo, who led the Bacone School of Art from 1938-1941.

Upon his return to Norman, Oklahoma for his senior year at the University of Oklahoma in 1938, Crumbo received an invitation to interview for a teaching position at Bacone. Crumbo was recommended for the position by the equally famous Acee Blue Eagle, the department’s first director and the man who is widely credited with helping shape what became known as the Bacone Style.

In Robert Perry’s biography of Crumbo, “Uprising!: Woody Crumbo’s Indian Art,” the Potawatomi artist described how he instilled a disciplined approach to the school of art’s training by demanding that attendees be full time students. He also broke a previous precedent of retaining the right to purchase his best student’s paintings, instead choosing to instruct them on how to market their art to potential customers.

In addition to the school’s focus on painting, Crumbo also formatted a curriculum that expanded artistic endeavors to sectors that would produce an income, like silver work, jewelry making and weaving.

As noted in Lisa K. Neuman’s “Indian Play: Indigenous Identities at Bacone College”, Crumbo explained that “what we want to do at Bacone eventually is to establish an art department that will be a cultural center for Indian arts and crafts.”

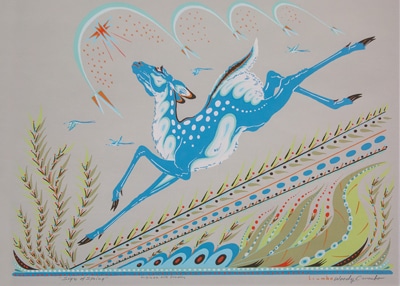

Though tied to the University of Oklahoma through Crumbo’s relationship with its prestigious art department which produced the wellknown Kiowa Five artists, the Bacone Style became known for bold colors and figures in motion. According to a 2014 James McGirk article on the school’s influence in This Land Press, the early products, especially pieces produced by those taught under Crumbo and Blue Eagle, had Art Deco influences. Also known as the “traditional Oklahoma style”, the artistry portrays an idealized version of Indian life with stylized use of form, color and outline. Though the style is now known as traditional Native American art, and went out of style for a time, its influence is prominent.

Crumbo left Bacone as the American entrance into WWII approached, but not because of the war. His longtime supporter and friend, President B.D. Weeks, had been accused of slander and resigned from the college he had helped grow. Crumbo and several staff members who had come into the college under his tenure resigned as well.

Though the Bacone School continued to produce artists in the years following the war, the impact of the first two department heads in Blue Eagle and Crumbo was a defining point in its development. In addition to his own legacy, Crumbo’s impact on the art scene continued on through his daughter, Minisa Crumbo Halsey, and son, Woody Max Crumbo. Halsey is a talented artist whose work has been shown throughout Europe and the Russian Federation while Woody Max Crumbo is a gifted silversmith. The elder Crumbo’s career spanned nearly 60 years and included major advancements in oil, silkscreen, tempera, pencil and watercolor. His work is in numerous museums and private collections around the world, including that of the Queen of England.