Contributed by Lenzy Krehbiel-Burton

Contributed by Lenzy Krehbiel-Burton

Come Oct. 1, be prepared for the pink-out. For more than 30 years, October has been observed as Breast Cancer Awareness Month.

About 40,000 women and 2,000 men annually are diagnosed with the disease, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show. Those figures do not include recently published American Cancer Society study results projecting a six-fold increase in cancer mortality rates in the next two decades.

The projected spike is credited in large part to the increase in obesity, with two-thirds of adults now considered obese or overweight. Obesity contributes to increased rates of 13 different cancers, including several found either exclusively or predominantly among women, such as breast, ovarian and cervical.

The increased risk associated with obesity comes on multiple fronts. In addition to upping the risk for diabetes and heart disease, extra fat cells increase the amount of estrogen circulating throughout the body, which has been linked to increased breast cancer rates in both pre- and postmenopausal women.

Nationally, American Indian and Alaska Native women have lower rates of breast cancer than their non-Native neighbors, with one in eight indigenous women diagnosed. However, it is less likely to be diagnosed before the disease reaches an advanced stage, thus increasing the mortality rate.

Kris Rhodes is the executive director of the American Indian Cancer Foundation, a national nonprofit that works to lower cancer rates in Indian Country through culturally appropriate programming, increasing the availability of reliable data that includes indigenous communities and capacity building through training and providing technical assistance.

Kris Rhodes is the executive director of the American Indian Cancer Foundation, a national nonprofit that works to lower cancer rates in Indian Country through culturally appropriate programming, increasing the availability of reliable data that includes indigenous communities and capacity building through training and providing technical assistance.

Among the breast cancer outreach programs hosted by the foundation is an annual Indigenous Pink Day each October. Scheduled Oct. 19, participants are encouraged to wear pink in support of breast cancer awareness and post a selfie tagged #IndigenousPink to social media.

For Rhodes, the higher breast cancer mortality rates, while disappointing, are not entirely surprising. In addition to the large swaths of Indian Country that do not have regular access to mammograms or other forms of preventative care, fear and modesty often keep many women from getting checked.

Despite that hesitation, the need for routine screening is still there.

“Cancer is showing in American Indian and Alaska Native women in younger ages,” she said. “We encourage women to start screening as early as their doctors will let them — 40 and up.

“Women have to be an advocate for themselves — it can make a huge difference.”

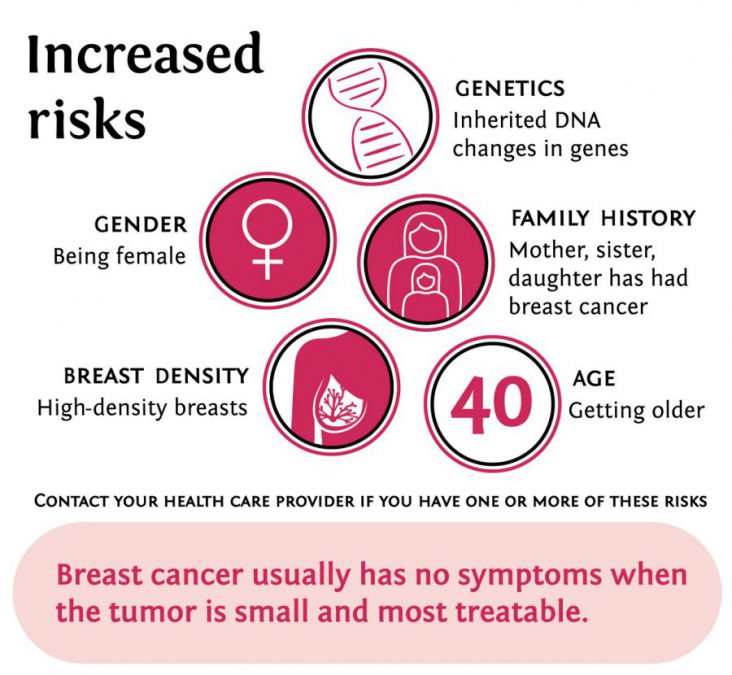

Some of the risk factors for the disease are preventable, such as binge drinking and not regularly exercising. However, others are unavoidable, including age, having a personal or family history of breast cancer, mutations to the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, starting menstruation before age 12 or having dense breasts, which have more tumor-masking connective tissue.

“It’s a common misconception that breast cancer is always genetic or that you only have to worry about it if someone in your family has had it,” Rhodes said. “However, the truth is that anyone can get breast cancer. In America today, though, if it’s caught early enough, it’s treatable.”

Early warning signs of breast cancer:

• New lumps in the breast or armpit

• Thickening or swelling of parts of the breast

• Irritation or dimpling of breast skin

• Redness or flaky skin around the nipple

• Nipple discharge other than breast milk or colostrum

• Any change in the size or shape of the breast

• Breast pain

For more information, visit americanindiancancer.org.