The Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center’s treaty gallery features several documents that defined Tribal relationships with the government, including peace, reservation and removal treaties. The Potawatomi signed 44 treaties with the federal government, more than any other tribe.

“The treaties help illustrate that Potawatomi groups were autonomous in the Great Lakes region, but that many came together when negotiating and signing compacts. Historical documents and transcribed speeches from this period indicate that tribal diplomats wanted entire communities to be present at treaty delegations. ,” said Blake Norton, curator.

The headmen “wanted everybody present and accountable to hear the terms of the treaty, because it affected whole communities and regions,” he said.

Treaty negotiations often took place within a council. When reputable Tribal members stepped up, people often followed behind, Norton said.

“Traditionally, councils were ruled by consensus. This same principle can be seen in the initial treaties between the Potawatomi and United States. Everyone had a role. Everyone had a voice,” he said.

Defining era

“For this section, we chose federal blue and confederate gray,” said CHC Director Kelli Mosteller. “Blue and gray, especially this blue, has a very institutional feel,” which offsets the colors featured in the sections on either side of this one.

“It plays to the messages that we want to convey,” Norton said.

The colors also encourage visitors to stop and take in this specific time period before continuing the tour.

“There’s also a lot of script in here, and it’s hard to read handwritten script from the 19th century,” Mosteller said. “You have to focus and try to interpret. With all the imagery around, we needed to strip it down so people can really focus in on the text.”

Peace Medals

During President Thomas Jefferson’s administration, the government began minting three sizes of silver medals to gift influential tribal leaders. The size given depended upon the receiver’s tribal standing. The left hand on the coin’s image represents Native Americans and the cuffed-sleeved hand with military details signifies the U.S. government. A tobacco pipe and tomahawk overlay each other indicating peace and friendship.

Those receiving coins would often fashion them into a necklace. Native leaders wanted others to see their coin, as many believed it represented a spiritual connection to powerful U.S. leaders.

The practice continued for several decades, and this section features examples from the administrations of presidents Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy Adams, James Madison and James Monroe.

The display case also features a pipe the CHC acquired in the 1970s.

“It definitely has its purpose in this space so visitors can understand that pipes were used during treaty negotiations,”

Norton said.

Peace Treaties

After the Revolutionary War, early treaties between the U.S. government and tribes served as peace contracts. These documents often called for prisoner release, defined tribal borders and included promises not to raid into agreed-upon territories. From 1789 to 1825, the Potawatomi entered into at least seven peace treaties, Norton said.

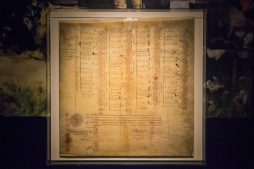

“This treaty ended the Northwest War, sometimes called Little Turtle’s War, that was fought between the tribes in primarily Indiana and Ohio to push back and defend against expansion into the Great Lakes,” Norton said, then pointed at the Treaty of Greenville hanging near the section’s entrance. “It’s a peace treaty.”

The Treaty of Greenville included terms of how to quell retribution and calm tensions.

When Native leaders entered treaty agreements, a scribe would write their name out phonetically and each leader would sign with a symbol representing both themselves and their villages, Norton said.

“As treaty making developed, tribal leaders began signing with a thumbprint and later an X. Signatures were often authenticated with a wax seal,” Norton said.

In 2006, the CHC partnered with the National Archives to obtain copies of these significant records.

The federal government rarely sent prints to the Native group(s) involved with the agreements, which is why the CHC had to partner with the National Archives.

“We were very specific in the way that we wanted each treaty to look. Our printing company hand cut each degraded piece and angle,” Norton said, while pointing at the Treaty of Greenville. “This is actually how the treaty looks.”

Divide and conquer

The government realized, with tribes spread throughout the Great Lakes, it was more advantageous to make treaties with smaller, individual groups rather than with huge congregations.

“U.S. leaders exploited tribal autonomy by making treaties with individual villages, rather than large regional bands. This tactic helped divide communities, as gifts and annuities were leveraged against those unwilling to sign,” Norton said.

Reservation Treaties

The continuous influx of white settlers to the Great Lakes region created tension, leading governmental officials to take a new approach. Unlike peace treaties, reservation treaties looked to separate the Natives from the non-Natives. By the early 19th century, treaties included terms setting reservation boundaries.

Through the Treaty of Mississinewa in 1826, Potawatomi ceded lands in northern Indiana. The government used the lands to build one of the earliest highways in the state, the Michigan Road, which connects Indianapolis to Lake Michigan.

In 1829, the Treaty of Prairie du Chien established reservations for some Potawatomi, Ojibwe and Ottawa headmen. In return, they ceded land in southwest Wisconsin and northern Illinois.

War of 1812 veteran and Potawatomi Chief Wabaunsee (He Walks at Dawn), became the third signer on the Treaty of Prairie du Chien. Due to his significant regional reputation, the document granted him the largest tract of land for his people.

Chief Metea

At this time, many Native leaders addressed governmental officials on behalf of their people including renowned Potawatomi Chief and warrior Metea.

“Chief Metea was a triple threat — a warrior, spiritualist and orator,” Norton said. “He helped defend Prophetstown at the onset of the War of 1812 and was wounded in battle. He was attacking American supply lines as they prepared for an attack and provided communication to leaders at Prophetstown.”

Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa, the Prophet, called Prophetstown home after moving their people from present-day Ohio to present-day Indiana.

Chief Metea’s arm became lame from the gun-shot wound. He hid his condition by covering up with a blanket.

“Due to his reputation as a warrior and leader, he could still rally troops,” Norton said. “He became a really well-known orator and spokesman for the Tribe, and he made his most popular speeches at the Treaty of Chicago.”

The following excerpt is from Metea’s Treaty of Chicago address.

“Our country was given to us by the Great Spirit, who gave it to us to hunt upon, to make our cornfields upon, to live upon, and to make down our beds upon when we die. And he would never forgive us, should we bargain it away. When you first spoke to us for lands at St. Mary’s, we said we had a little, and agreed to sell you a piece of it; but we told you we could spare no more. Now you ask us again. You are never satisfied! We have sold you a great tract of land already; but it is not enough! We sold it to you for the benefit of your children, to farm and to live upon. We have now but little left. We shall want it all for ourselves. We know not how long we may live, and we wish to have some lands for our children to hunt upon. You are gradually taking away our hunting-grounds. Your children are driving us before them. We are growing uneasy. What lands you have, you may retain forever; but we shall sell no more,” Chief Metea said.

Marshall Trilogy

Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall helped shape the current relationship between the federal government and tribes through three specific Supreme Court decisions now known as the Marshall Trilogy.

The Marshall Trilogy clearly defined tribal sovereignty and gave the federal government sole authority over Natives by making them wards of the government. The cases also determined that Indians could not sell the lands they claimed to any entity except the U.S. government.

“The three cases helped define U.S./tribal policies we see today and the authority tribes have to own, sell and defend their lands,” Norton said.

After the Supreme Court decisions on the cases, the executive branch retained authority to oversee and enforce the rulings. Under the authority of President Andrew Jackson, the official era of Indian removal began.

Visitors to the CHC can use the interactives within this section to learn more about these Supreme Court decisions and their impact on the Tribe.

Removal Treaties

“From the first treaty signed in 1789, all are focused on the exchange of land and the removal of tribes for settlement,” Norton said.

The Treaty of Chicago became one of the largest land secessions that the Potawatomi experienced, forcing the Potawatomi to cede approximately 5 million acres. The treaty required the Potawatomi move to a reservation near Council Bluffs, Iowa.

“By the 1830s, people had to begin focusing on the welfare of their immediate groups rather than regional bands,” Norton said. “For many, this did not extend past their family units.”

In August 1835, 800 Potawatomi began making their way to Iowa, but not before dancing through the streets of Chicago to grieve and conduct their last ceremony on ancestral lands. By 1837, most Potawatomi had made the migration west except for a few groups including Chief Menominee’s people, many of which eventually became Citizen Potawatomi.

Whiskey Treaties

Chief Menominee and his followers refused to leave their ancestral lands because federal Indian agent Abel C. Pepper gave whiskey to young leaders to secure numerous treaties from 1834-1837.

“Alcohol was a common complaint among leaders during this time. Most felt it was a way to divide villages and make them weak. As old leaders refused to negotiate, young men were appointed chiefs by the U.S. government,” Norton said.

“People began to figure out that the government wasn’t upholding the terms of the treaty, and it became more and more difficult for people to sign onto it,” Norton said.

Menominee wrote agent Pepper in 1838 saying, “The President does not know the truth. He, like me, has been imposed upon. He does not know that you made my young chiefs drunk and got their consent and pretended to get mine. He would not drive me from my home and the graves of my tribe, and my children, who have gone to the Great Spirit, nor allow you to tell me that your braves will take me, tied like a dog.”

U.S. leaders’ solution to the “Indian Problem” included removing Natives to Indian Territory where each tribe could be a sovereign nation away from non-Indians. These policies created lasting challenges across Indian Country and led to the Tribe’s forced removal from the Great Lakes region to present-day Kansas.