Throughout Potawatomi history, women have contributed to Nishnabé communities in innumerable ways. Some prominent female leaders since the 1800s include Massaw, Watseka, Mary Ann Benache, Joyce Abel, Beverly Hughes and more.

“Women have always had a central role in our life. … Our societies are structured differently than most Euro-American cultures historically were. Our society did not have the same Western understanding that men are at the top. While women may have different roles, it doesn’t mean they had to be subservient,” said Dr. Kelli Mosteller, Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s Cultural Heritage Center director.

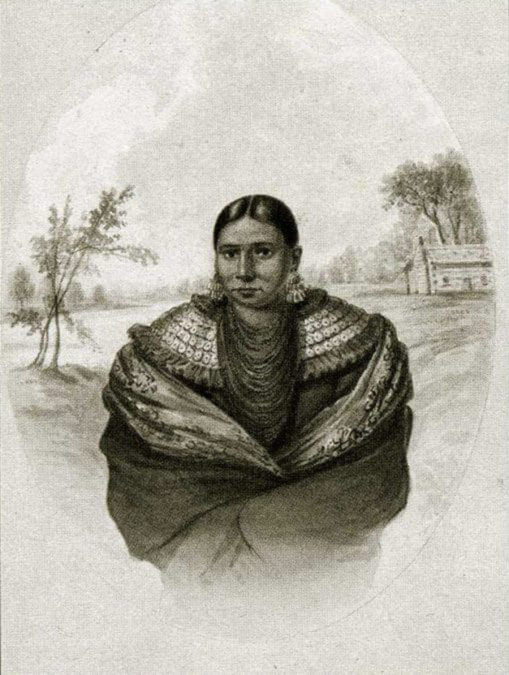

Massaw

As the daughter of Potawatomi Chief Wassato and wife of a French fur trader, Massaw was a respected individual within Potawatomi communities.

“She may have been from an esteemed family, but she was the one who secured her place within powerful circles,” said Blake Norton, Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s Cultural Heritage Center’s curator.

She had a reputation as Tribal ogema (headman or headwoman) and prominent entrepreneur near Lake Keewawnay in Indiana.

“She was a woman of her time,” Dr. Mosteller said. “She absolutely saw the world around her and understood the kind of business that would make her successful. … She understood what the people and the circumstances of her time and place needed, and she made the most of that.”

Before the Potawatomi forced removal on the Trail of Death, Massaw ran a successful business out of her two-story home and had the same ranking as men during numerous treaty negotiations and signings.

“Massaw could read a room,” Dr. Mosteller explained. “She could read the writing on the wall, and she was going to do what she needed to help herself, her family and her Tribe.”

While women have always held equal importance in Potawatomi society, the cultural customs did not always translate to political and legal dealings with other countries and entities. But, her cunningness and economic approaches opened the door for her to receive political standings other women at the time could not achieve.

“It’s just speculation, but this may be why she was noted as a man on the first two treaties she signed,” Norton said. “Women did sign treaties, but this would come a couple of years later as more land was being sold and reserved.”

Massaw presented herself in fine clothing. In English artist George Winter’s diaries, he noted her dark, smooth hair and bright-colored clothes adorned with ribbon applique and silver brooches and stately earrings.

“The appointment of her dress were expensive, including her moccasins, which were neatly made and handsomely checkered,” Winter wrote.

She also enjoyed playing card games, and many knew of her expertise.

“She understood the person who she was doing business with, whether that was at the card table, doing a transaction for goods or getting somebody to pay up. She was not a shrinking violet, ” Dr. Mosteller said.

Fight for representation

Massaw’s keen mind and understanding of Tribal affairs made her an important signatory during the Treaty of 1861 and its 1866 amendments. Although she had signed treaties in the past, four other women also had a role, including Totoquah, Otter Woman, Mary Jutions and Pnah-zuea.

“For the 1861 treaty, I think it’s critical that women were signatories because it was such a shift with land ownership becoming the new basis for authority and power,” Dr. Mosteller said.

The Treaty of 1861 laid the groundwork for Potawatomi to receive allotments and the opportunity to become U.S. citizens or remain living communally on 11-square-miles. It separated the 2,170 Kansas Potawatomi into two distinct groups, with 1,400 choosing allotments. Each Tribal member received parcels of land based upon their community and family standings.

During this time, Potawatomi women, represented by Massaw, Totoquah, Otter Woman, Mary Jutions and Pnah-zuea, petitioned for the ability to receive head of household recognition.

“Because these Potawatomi women were the ones who were eligible for land allotments, not their white husbands, they understood that they needed to have a seat at the table,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Although their requests did not make it into the 1861 treaty, they continued pushing for their rights.

Because of these efforts, “we had the amendment of 1866 that came back in and changed the treaty to say that Potawatomi women could be the head of the household and that she should be able to get a full allotment — not the 80 acres or 40 acres, whatever it may be, as a dependent,” she said. “She is not dependent of anybody. She is the head of her household, and her relationship to her white husband had nothing to do with it.”

Although not all of the five women had officially signed treaties in the past, they had experience with prior negotiations.

“They understood what this process was about, and they understood that making this decision to change their Tribe’s relationship with the federal government was one that was going to impact them just as much as it was the men,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Because of their standings and Potawatomi cultural traditions, men across the community supported the women and their requests. The five female signatories’ tenacity forever impacted Potawatomi women’s ability to receive the same recognition and power as men through the federal government.

Watseka

Watseka — Watchekee — (Overseer) was a prominent Potawatomi woman during the 19th century. She was the daughter of Monashki and Potawatomi/Odawa Chief Shabonna. During the War of 1812, Shabonna (Built Like a Bear) was an ally of Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa. He joined Potawatomi leaders Waubansee, Winamac, Main Poc and others.

Watchekee was born around 1810. Records indicate her birth happened during a bright star. Chief Shabonna raised her in a Potawatomi village, and she held a reputation for both her brains and looks. After the Potawatomi signed the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, she removed to Council Bluffs, Iowa, in 1837.

Once she moved west of the Mississippi, Watchekee continued yearning for her homelands, and she often traveled by foot back and forth to the Great Lakes region. Some estimate she walked more than 6,000 miles during this time.

Watchekee was one of the very few to live in the Great Lakes, experience removal and eventually settle on the reservation in Indian Territory. Her influence in the Great Lakes region remains today with the city of Watseka, Illinois, near the Indiana border derived from her name. According to Daily Journal, community leaders renamed the city in 1865 from Middleport to Watseka to honor her kindness toward settlers. Today, a large mural in town features Watchekee, serving as a visual reminder of the community’s past.

Mary Ann Benache

Mary Ann (Anne) was the daughter of the fierce warrior and leader Segnak or Benache. Segnak held a high standing in the Milwaukee Potawatomi villages as a headman, and he was invited to discuss tribal affairs with President Thomas Jefferson.

He fought alongside Potawatomi and other Native Americans during the War of 1812 and signed eight treaties. He assisted fellow Potawatomi with receiving claim to land and developed real estate businesses through partnerships with important traders like Alexis Coquillard, who became the founder of South Bend, Indiana. Segnak’s daughter Mary Ann wed Coquillard’s business partner Edward McCartney.

Due to these connections, Segnak and his family avoided removal. Mary Ann divorced McCartney and eventually married a Potawatomi warrior named Peashwah. After Segnak passed away, Mary Ann inherited his land and became one of the most prominent landowners in Kosciusko County, Indiana.

“She inherited a lot of her gumption from her dad, who was a fierce warrior and brilliantly negotiated the politics of his time,” Dr. Mosteller said. “Often women, if they inherited land and they married, then the ownership transferred into their husband’s name. That did not happen in this case.”

Mary Ann employed numerous efforts to ensure her family’s land remained under her domain.

“I think she adopted a lot of things from her father, including his warrior spirit,” she said. “He was feared on the battlefield, and I think she is an example of how you can be absolutely a woman of your time but also refuse to let those things that have been handed down to you pass into other hands.”

Mary Anderson Bourbonnais

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Citizen Potawatomi overcame many obstacles, including relocating to Indian Territory and maneuvering the ever-changing relations with the federal government. One of the leaders who rose to the challenge at this time was Mary Anderson Bourbonnais.

Bourbonnais understood the Potawatomi battles were no longer in the hills, forests and fields surrounding the Great Lakes but rather in the halls of government. She began letter-writing campaign efforts that formed a foundation for how the Citizen Potawatomi Nation continues operating today.

“She worked the system,” Dr. Mosteller said. “First, she went to the Indian agent, and if he didn’t give her the answer she wanted, she would go to the commissioner of Indian affairs. And if he didn’t give her the answer she wanted, she brought it to the president.”

Bourbonnais and her husband Antoine were among one of the first Potawatomi families to make the trek from Kansas to the Pleasant Prairie community in present-day southern Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma. After arriving, she became involved in the Quaker church and eventually served as the first Sunday school superintendent. Most knew her as “Aunt Mary,” and she also helped others in the territory as a midwife and doctor.

Although Bourbonnais had a caring touch, this did not undermine her tenaciousness. Instead of backing down in the face of adversity, Bourbonnais and other leaders during this time pressed forward.

“She is a good example of this unwillingness to take the answers they don’t want to hear at face value,” she said. “And her descendants — you had other Andersons — who would eventually hire attorneys and go to Washington and argue on behalf of the Tribe.”

The Bourbonnais family eventually moved further north, and their cabin remains standing today next to the Cultural Heritage Center. It serves as a reminder of the lasting impact she had on the Nation, which continues to uphold her legacy by petitioning for sovereignty and Tribal rights through Congress, courtrooms and more.

“We don’t sue because we love to sue,” Dr. Mosteller explained. “We are litigious, and we file lawsuits and participate in lawsuits because we have learned that if you don’t fight for every bit of sovereignty you are due, it will be seized. And, they will keep coming.”

Joyce Abel

Bourbonnais descendant Joyce Abel was born on Nov. 1, 1936, and passed away Sept. 5, 2011, but her mark on CPN continues.

She had a profound impact on Citizen Potawatomi Nation Health Services. Abel’s CPN career spanned more than 30 years, during which she designed and directed the first health clinic and FireLake Wellness Center. She also established the Health Aids Program.

“I look at our health clinics and the advancements that have come from those endeavors — the Wellness Center and the Health Aids program — and see lasting programs that do exactly what she wanted them to do in helping people,” said CPN Information Technology Director and Joyce’s grandson Chris Abel.

“I cannot help but smile when I use the services that I am allowed that she had a hand in creating or improving.”

Many remember her contagious energy and ability to make work enjoyable, no matter the task.

“She made me believe that as a Tribal member, I could come back and do something positive for my community,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Abel understood in the importance of service to community as well as encouraging future generations of Potawatomi to find their role in the Nation.

“She had that sort of healing spirit, and I think for those of us wondering if all the years of school and efforts to become a professional can be used to help my community, she is a shining example of that absolutely, yes I can,” Dr. Mosteller added.

Beverly Hughes

At one point in the Nation’s not so distant history, the Tribe operated out of a small trailer, and volunteers oversaw daily operations, including Bruno-Rhodd-Bourbonnais descendant Beverly Hughes.

Hughes served as the Secretary-Treasurer on the Nation’s Business Council in 1970. During this time, tribal self-governance provided Native nations greater independence. As part of this, Hughes received the duty of designing a Tribal seal and had a role in selecting an official name.

“They said they were going to spell it the same as the county, but I told them that we were separate from the county. We were an entity unto ourselves, so we made it Potawatomi,” Hughes said in a 2013 Hownikan article.

“That was absolutely Beverly, as she would look at the circumstances and say, ‘We need this.’ And she would just do it. Did she always have the training? No, but she would get it done,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Seeing the need to inform CPN tribal members about federal funds, Beverly Hughes created the Hownikan.

“All I was trying to do was give people an update on what we were doing and what services we provided,” Hughes explained. “It seemed pretty popular, so from then on we tried to produce it every quarter to keep our members informed.”

The Hownikan remains today and reaches thousands of Tribal members every month.

“As I go through the archives, her signatures are all over everything. She was where we needed her to be. She took on things that the community needed, and when a call was put out for help, she was always there,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Hughes had a resilient spirit, like so many Potawatomi women who came before, but she also approached life filled with love and hope.

“I don’t think I would have felt confident making a lot of the decisions and feeling like I deserved the position I’m in without (Beverly) and women like her,” Dr. Mosteller explained. “She loved her Tribe deeply, but she was not hesitant to be critical when she felt criticism would make us better.”

While each of the women mentioned left lasting marks on the Citizen Potawatomi people, throughout time, countless Potawatomi women have risen to the challenges and kept the Nation strong and prosperous. Learn more about these leaders as well as others by visiting the Cultural Heritage Center or researching online records, including the archives and encyclopedia featured on the CHC’s website, at potawatomiheritage.com.