During the 1800s, Tribal contracts with the federal government in the form of treaties continued to cede more Indigenous land for the benefit of white settlers. A cultural renaissance quickly spread across the United States that encouraged citizens to move westward, justifying property theft in the name of Manifest Destiny. Potawatomi headmen like Chief Ashkum (More and More) addressed crowds on behalf of the Potawatomi at this time, bringing to light the long-term, negative implications of losing the land and connection to the Great Lakes region.

“He was a powerful speaker for the Tribe’s rights, recounting their history as a people and relationship with the U.S. each time he spoke,” said Blake Norton, Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center curator. “He acknowledged and was a part of early land negotiations and cessions. However, he refused further deals and rallied others when he understood that the U.S. wanted all of the land and that the Tribe was at the precipice of cultural loss.”

Treaties

Ashkum’s village was located in north-central Indiana along the Eel River, a Wabash River tributary. He signed the 1821 Treaty of Chicago, which involved the Odawa, Ojibwe and Potawatomi. This treaty ceded nearly all Potawatomi acreage in the southwestern quarter of Michigan.

Five years later, Ashkum’s signature appears on the Treaty of Mississinewa, which provided the acreage needed to build one of Indiana’s earliest highways, the Michigan Road. The Potawatomi forced on the Trail of Death used the road on the initial leg of the 660-mile forced removal in 1838.

Tribal leaders Weesiones and Ashkum established a reservation for their bands through the Treaty of Tippecanoe in 1832. Within a few years, Ashkum’s name appeared without his knowledge on the Treaty of Potawatomi Mills, and this allowed a transferal of the reservations’ ownership without either of the chiefs’ approval.

“Revealed later, many of the known conspirers to this fraudulent sale are listed directly below Ashkum on the treaty. His name again is curiously buried among conspirators on the Treaty of Yellow River, signed on Aug. 5, 1836, that ceded the reservations established for other Indiana headmen just the day before his and Weesiones’ reserve was established,” Norton said. “This is strange because Ashkum would have known that his land was in jeopardy and confronted the issue, but there is no account of this recorded.”

His signature appears once more on the Treaty of Chippewanaung, which wrongfully authorized the sale of both Weesiones and Ashkum’s earlier reservations.

“Everything comes to the surface when Ashkum, Weesiones and other headmen gathered to collect their annuities and learned that many of their lands had been illegally ceded,” Norton said. “They rejected the sales and threatened those involved with death. A large riot broke out between Tribal leaders, assisted by local businessmen for and against the claims.”

Stolen lands

Ashkum, Weesiones and other Tribal leaders vowed the property cessions were illegal and pleaded with federal agents that the president of the United States was unaware of these treaties and would not approve.

“They were dismissed and ultimately overruled by agents, citing a majority vote per the treaty signatures and understood support from community factions that were now deemed in control,” Norton said.

Sadly, federal agents saw the potential impact of Ashkum and leaders like him within the Potawatomi and other Native groups in the area. Because of this, U.S. agents replaced Ashkum with government-approved Tribal leaders and orators.

“These guys are labeled ‘government chiefs,’ but all were respected in the community and covered a generational gap that helped gain numbers,” Norton explained. “Some were respected veterans of past wars, others were closely associated with local businessmen, and others were young up-and-comers on the path to leadership. Many of the younger faction were heavily indebted to local traders, while others vied for personal gain and power.”

Historical records note Ashkum’s age as at least 50 in 1837, which could indicate he contributed in the Northwest Wars and the War of 1812.

“There is no record of him participating in war, but it would be unusual for him to not have, given the time frame, his status and that of other headmen in the region that we know were highly active,” he explained. “As a nod to his status and recollection of Tribal history, he was the original speaker for the Potawatomi of that region of Indiana during the 1830s.”

Recollections

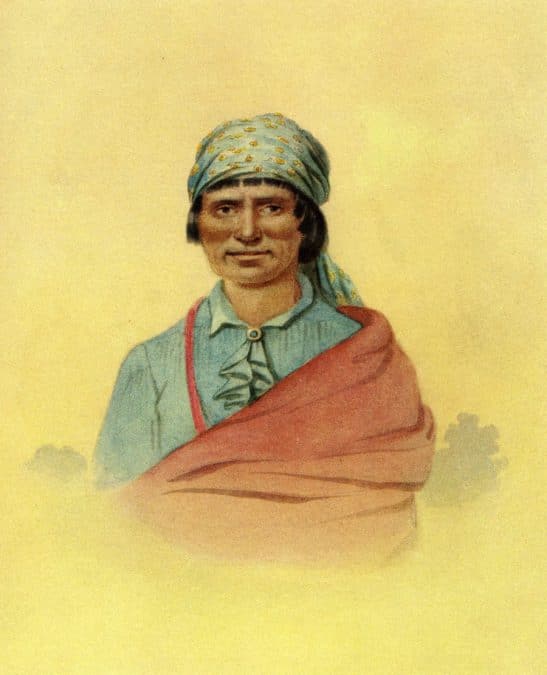

English artist George Winter captured sketches and paintings of the Native Americans living in the area and wrote about Ashkum in his diary.

“Ash-kum was among those old chiefs who retained their prejudices against having themselves portrayed — or from the secret contempt for being remembered among white men through the medium of the pencil. Yet he was amused at others whom I painted, and was ever ready with his spicy joke upon his likenesses,” Winter wrote.

In 1838, federal agents and volunteer militia forcibly removed the Potawatomi, including Ashkum, on the Trail of Death.

“Ashkum was strongly attached to his native forests and lakes — and left Indiana with a deep feeling of regret,” Winter said.

Like numerous tribal leaders at this time, once Ashkum headed west, he no longer appeared on any historical records. However, recounting his life builds a greater understanding of the true nature of U.S. Indian policy. During Ashkum’s lifetime, the government justified its negative actions toward Native Americans on behalf of Manifest Destiny. Federal policy forcibly removed Native Americans, like the Potawatomi, and created a culture to exploit Indigenous groups by any means necessary.

“The story is also powerful because it’s not unique. Too many faced the same odds during this period,” Norton said. “It was an era of betrayal, opportunity and ultimate loss that is the poster child for U.S. and Native American relations.”

Learn more about Ashkum and this period of Potawatomi history within the Cultural Heritage Center’s Treaties, Words & Leaders That Shaped our Nation gallery.