Joshua Nelson remembers visiting his uncle’s home as a kid and seeing American Indians on TV. Sometimes they were the real deal — actual Native American actors. Other times they were white faces hiding behind red paint. Either way, they would catch a bullet courtesy of John Wayne more often than not.

Still, the OU interim director of film and media studies wonders what it could have meant to see a Native American man like his uncle or a Cherokee boy like himself on the screen. He wanted to see something more than the silent sidekick or the dozens of whooping extras destined for the wrong side of some handsome cowboy’s rifle. Always missing was a depth of character, a reason to invest, to feel and to believe.

“But I think what a difference it would have made if every time I went over there as a young person, loving movies the way I do … if we’d have had stories where the Indians were the heroes. The Indians didn’t die. The Indians were smart, were funny, were compassionate,” Nelson said. “Who knows, maybe I would’ve been smarter, funnier and more compassionate or, more simply, felt like there was a place for me to tell stories like that.”

Nelson said he believes the film industry has come a long way since those days, but misrepresentation and underrepresentation are both still very current problems. Native American perspectives and experiences are not being captured or shared. Nelson intends to combat this problem directly in the way educators so often do, by teaching.

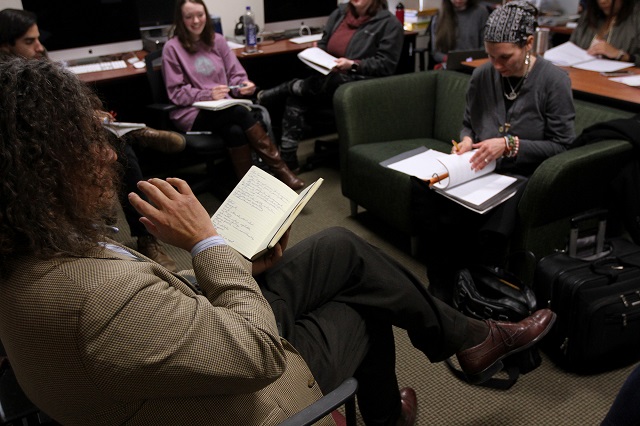

This semester is the first to offer Nelson’s new class, Telling Native Stories. His creation aims to put more Native Americans behind the camera, a position that many from Native American communities feel is not for them, Nelson said. He is putting thousands of dollars worth of gear in the hands of his students and is working to show them otherwise.

From screenwriting, to camerawork, lighting, audio, editing and eventually distribution, Nelson plans to arm his students with everything they need to express themselves through film.

The class’s focus on Native-centric stories does not mean only Native American students should enroll — the class is inclusive, with a dozen members of both Native and non-Native heritage. Nelson only asks that the work come from a place of authenticity and respect for Native American culture.

“The problem that I have seen is that in this state, with nearly the highest Native American population, we have practically zero media representation,” Nelson said. “We have no room for those people to tell their stories, and so I want to carve out that room and I want to prepare people to tell those stories.”

Brittany McKane, Native American studies and anthropology junior of Muscogee and Seminole descent, said she is not the Native American typically seen on TV — the living relic left over from a mythical past.

Most Native American depictions today may as well be props hauled in from a Hollywood warehouse — dusted off and decorated, camera ready, but with little substance, McKane said. When they speak, the thoughts of non-Natives Americans come out, she said.

“White characters have a backstory. They are seen as modern, complex human beings, but that same kind of personality isn’t afforded to Native American characters,” McKane said. “I think somebody who is Native, who has lived that and seen that kind of complexity within other Native people could be able to depict that better than somebody who hasn’t.”

McKane said she cannot see any piece of herself in these characters or find a place to stand in these stories.

“You don’t ever see Indians with law degrees. You don’t ever see Indians going to med school. Indians who are out there making a difference, you don’t see it. That absolutely shapes the way the public sees us,” McKane said. “We are such a small portion of the population that people don’t really come into contact with us and all they see are those representations and those stereotypes.”

Telling Native American stories has a broad goal, and to achieve it Nelson is looking outside of campus as well as toward the next generation of filmmakers.

“I’m old and past my prime,” Nelson said. “I will never make the great American Indian movie, but maybe my students who are working on these kinds of stories will.”

Thanks to a partnership between OU and the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Nelson will reach more than his own college-aged students with the class.

Throughout the semester, Nelson’s students will take several field trips to Potawatomi tribal lands to pair up one-on-one with high school students picked for their abilities or interests in film. Nelson wants to further encourage the passions of all involved, to exchange techniques and knowledge, and to impart whatever wisdom they may have gained along the way, he said.

Tesia Zientek, director of the Department of Education for the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, is the other side of the partnership. Zientek provides the high schoolers, and Nelson provides the gear and his own recently trained students to mentor them, hoping they will continue to learn through the process of teaching.

Though Zientek received her diplomas and bona fides from Notre Dame and Stanford and could have put down roots anywhere, she felt a debt was owed. A duty and a love for her tribe brought her back home, back to Oklahoma.

She accredits her tribe and her upbringing for who she is and what she has achieved and said it simply would not feel right to take all the knowledge, skills and experience she has acquired elsewhere, like she has seen many others do.

“As far as tribes go, you see a lot of brain-drain happening, and I didn’t want to be a part of that,” Zientek said.

Zientek’s help was needed to get Nelson’s project up and running and to help coordinate things from the other side going forward. She did not need much convincing, she said.

Like McKane and Nelson, Zientek said she finds media depictions of Native Americans lacking and, at times, outright harmful. Not only does it inform the way non-Natives see American Indians, she said, it affects the way Natives see who they are, what they are capable of and what is expected from them.

“If you are a white male in America and you turn on the TV, you’re going to see a lot of different ways to be

white and male,” Zientek said. “You can see different versions, different possible selves. For Native Americans that’s not the case.”

The chance to help cultivate a culture and community of Native American filmmakers and visual storytellers is not an offer Zientek ever expected. There is a huge emphasis among Native Americans to give back to the tribe, she said, to contribute, to help it to grow and thrive. Media, film and the arts in general are not often thought of as being the most practical ways to do this, she said.

Zientek said she hopes Nelson’s class is a success and highlights the benefits of artistic pursuits in the ways they can benefit a people that may not be immediately seen or felt.

This is uncharted territory for both OU and the Potawatomi. More than a class, Nelson wants to breathe new life into the longstanding tradition of Native American storytelling, and he thinks he’s picked the right place and just the right people to do so.

“I have never in my decade of teaching felt a more palpable energy from a class than this one,” Nelson said. “Every student in there is buzzing with readiness to get out there and start doing this kind of work.”

This article originally ran in OU Daily and has been reproduced here with its author’s permission.