The personalities of Native American leaders of the pre-removal era are less widely covered than their American counterparts. For every dozen chronicles of American statesmen or military leaders from the early 1800s, there are significantly fewer documented accounts relating the lives of tribal leaders of the same era. Though resources are few and far between, one account offers insight into the thoughts and experiences of an early 19th-century tribal leader.

The personalities of Native American leaders of the pre-removal era are less widely covered than their American counterparts. For every dozen chronicles of American statesmen or military leaders from the early 1800s, there are significantly fewer documented accounts relating the lives of tribal leaders of the same era. Though resources are few and far between, one account offers insight into the thoughts and experiences of an early 19th-century tribal leader.

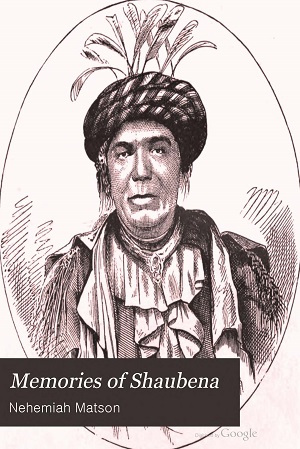

Written in 1880, author Nehemiah Matson chronicled the incredible life in “Memories of Shaubena.” Like many contemporaries in his time, Matson, a prodigious chronicler of Great Lakes-area tribes, sought to capture the fading American West in print. As with any account more than 130 years old, the language and terminology used by Matson appears out of place or even offensive in the present era. Yet his chronology of Shaubena’s experiences is infused with admiration.

As Matson notes in the book’s prologue, “The memory of Shaubena should be preserved, and a record of his beneficent deeds go down to posterity, so that coming generations may learn to honor the name of this noble red man.”

Born sometime between 1775 and 1776 in a village along the Kankakee River in what is today’s Will County, Illinois, Shaubena was the son of an Odawa (Ottawa) chief. His father and family had fled their traditional homelands in Michigan after allying with the defeated Odawa leader Pontiac against the British in the French and Indian War. As a child, Shaubena and his family traveled from Illinois and resided in Canada for a time before returning to the village in which he was born. This journey proved to be the first of many in Shaubena’s life, as he would travel throughout what was then the farthest reaches of the American frontier.

His ties to the Potawatomi came as a young man, when he married the daughter of the Potawatomi Chief Spotka. Upon Spotka’s death, Shaubena became the tribe’s leader and later facilitated its move to a different village in modern-day De Kalb County. It was during his youth that Shaubena also travelled with what Matson describes as two “Ottawa priests, or prophets,” who instructed Native Americans on a new system of religion. As a result of this affiliation, Shaubena travelled the region and grew familiar with a number of different tribes and their leaders, including with the legendary Shawnee leader Tecumseh. A friendship ensued and the Potawatomi leader journeyed extensively in the western lands bordering the nascent United States to gain Indian allies against further American encroachment.

From stops with the Winnebagoes and Menomonees in modern-day Wisconsin to a months’ long journey south to live amongst the Creeks, Cherokees and Choctaws, Shaubena and Tecumseh steadily sought to build an alliance that could halt the westward American expansion.

The effort though, was doomed to failure. Years later, Shaubena explained to Matson that he was next to Tecumseh when the great Shawnee warrior was felled at the Battle of the Thames.

In 1816, he was amongst the signees of the Treaty of Saint Louis, which ceded many of the Indian lands between the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers from Wisconsin, Illinois and St. Louis. This signing proved to be the first step in a long, sad journey for the Potawatomi leader and his people. Its end result would be his tribe’s banishment from their traditional homelands to a reservation in Kanas. Matson chronicles the circumstances of the situation facing the Potawatomi in 1836 when the federal government initiated what would become known as the Trail of Death.

“Their wigwams have disappeared from the groves, the smoke of their camp fires no longer ascends above the trees, the crack of their rifles and bay of their dogs are no more heard, their canoes are not seen on the rivers and lakes, and their once familiar war whoops have ceased to echo through the timber. The sacred places of the red man have been desecrated by the whites, and by them the graves of their fathers have been plowed over, and the guardian spirits watching over them driven away.”

The old chief’s connection to today’s Citizen Potawatomi Nation lives on through his daughter Mahnawbunokwe, who married the French trader Jean Baptiste Beubien.

The book, available online for free through Google’s Books platform, is as close to a primary account that one will find with a Potawatomi leader from the pre-removal era. While “Memories of Shaubena” may not be up to par with contemporary scholastic rigors, it provides a fascinating Native-centric perspective often lost in Western histories.