Haskell Indian Nations University held Keeping Legends Alive in September 2018 to celebrate two big occasions in the school’s history. The first was to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I, and Haskell’s 1926 Indian Celebration commemorated the dedication of the university’s football stadium and archway. Organizers asked Citizen Potawatomi Nation Director of Housing Scott George and his mother Dolores Scott to attend. The Georges’ were invited on behalf of Scott’s great-grandfather, Daniel Scott, who was a member of the Osage Nation and World War I Army veteran.

Daniel Scott’s endeavors left a lasting mark on the university and Indian Country.

“It meant a lot to us to have the family present as we honored their relative for both his contribution to the Haskell celebration but also his service as a tribal WWI soldier,” said Haskell Cultural Center and Museum Director Jancita Warrington.

Haskell’s stadium and arch memorialize the 415 students who fought in what was known at the time as “The Great War.” Native American soldiers served in large numbers, even though most were not considered U.S. citizens until 1924 when Congress passed the Snyder Act. This piece of legislation granted U.S. citizenship to all Native Americans across the country.

Records indicate Daniel Scott told the Haskell football coach and stadium fund campaign chair the university would have “the biggest powwow of all time” in conjunction with the unveiling. However, incorporating Native traditions into the event proved problematic.

“At that time, there was a ban on Native Americans having any dances, religious ceremonies or feasts,” George said. “It’s our understanding that my ancestor wrote a letter to Congress asking permission to have this celebration.”

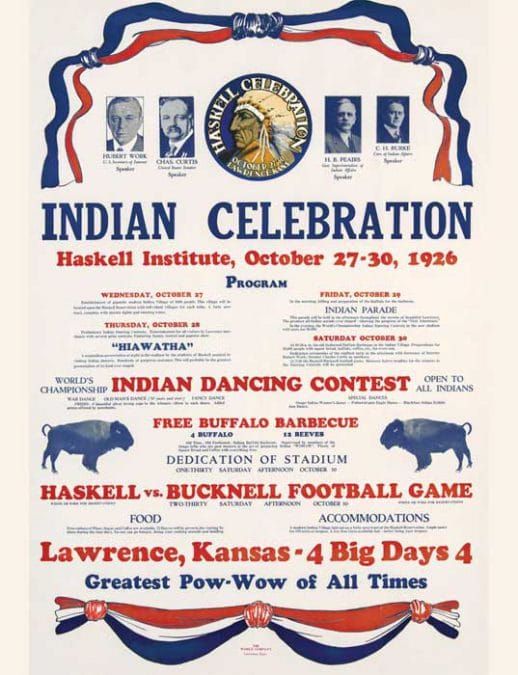

Approximately 250,000 people attended the Indian Celebration held Oct. 27-30, 1926. Because of Daniel Scott, the event included traditional dancing and other Indigenous-centered programming, bringing together Natives and non-Natives alike.

“At this time, the general American public did not have too many open encounters with tribal peoples, especially not in their own lands or places,” Warrington said. “The only kind of information extended to the public was the information produced in government reports, the caricatures provided by the local newspapers or the shows that romanticized the Indian/non-Indian relationships like Buffalo Bill.”

U.S. Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work also addressed Indian Celebration attendees.

“The speech was read on behalf of his boss — the President of the United States Calvin Coolidge — who could not attend the event because he was scheduled to dedicate the Liberty Memorial in Kansas City as a WWI memorial 12 days later, on Armistice Day Nov. 11, 1926,” she said.

Daniel Scott’s letter writing efforts not only helped Native Americans lawfully incorporate their traditions into the Haskell Indian Celebration in 1926, but it also helped pave the way for the American Indian Religious Freedom Act that Congress passed in 1978.

“All he did was write a letter,” George said. “I could do that. You could do that.”

Without Daniel Scott’s vision, the display of Native American culture at the powwow may not have been possible.

“To have the powwow as a part of the event, it really launched this intertribal powwow culture we all participate in today,” Warrington said. “This particular impact extended into Indian Country and began a cultural resurgence and unified pride amongst Indian people.”

Because of Daniel Scott’s service to the U.S. and Indian Country, a group of Osage singers continues to sing his song annually at the Grayhorse War Mothers celebration in remembrance of his impact to this day.

“One of the highest honors one can receive in a tribal society (is) to have a song composed for them in recognition of something they did in or for their community,” Warrington said.

Acknowledging the strides of those Native Americans who came before ensures the well-being and future of Indian Country.

“Tribal peoples’ recognition and understanding of our history is vital to serving our communities,” Warrington said. “If we don’t understand our history, it makes it more challenging to understand who we are today and where we want to take our communities in the future.”

Read more about the Haskell 1926 Indian Celebration and Daniel Scott’s influence here: cpn.news/haskellmilitary.