For those who have been at the tribe’s annual Family Reunion Festival the last three years, the tradition of honoring the general council meeting’s eldest attendee has been reserved for one tribal member in particular. At the time of writing, 99-year-old George Hamilton had just received his third straight honor from Tribal Chairman John “Rocky” Barrett for his attendance at the 2016 general counsel. While many may know Hamilton from these brief instances, the story of this Citizen Potawatomi’s long life provides a fascinating window into the 20th century.

On July 15, 1916, Hamilton was born on a farm west of the Oklahoma City Stockyards, in an area that today is part of the city’s suburban sprawl.

“It was in the country at the time, I guess it’d be on the east side of Grand Boulevard and north of SW 15th street,” recalled Hamilton.

Like many in that era, Hamilton split time between work on the farm and classes at Bishop John Carrol School, Central High School and Classen High School. However, a stipulation in the latter’s graduation requirements kept Hamilton from getting a high school diploma.

“It got to the end of the year, and I had the credits to qualify to graduate, but they required you be in school year round. I had bought a feed store when I was 16 and worked there, so I never did graduate.”

Hamilton’s father and uncle had originally purchased a building in Oklahoma City’s Packing Town District that would house the feed store for their business as horse traders. Their interest in that side of the business left the feed store unattended, so Hamilton, with his father as a co-signer, took a $300 loan out and opened for business. As a 16-year-old, he would work and live in the feed store’s 6×6 foot office and attend school, recalling that he rode the city’s long-since-abandoned street car system so he could attend classes.

As Hamilton tells it, his venture “turned out alright.”

“It was sparsely populated out south of the stockyards at the time,” he recalled. “People had milk cows and chickens all out in there. That’s what my business was, just small time sales.”

His lucid recollection of the landscape of 1920s and 1930s Oklahoma City provide an intriguing glimpse into the city’s first century, especially for those who only know the metropolitan area as it is today. In what today are sections of suburban sprawl and paved four-lane streets, Hamilton can tell you the paths and section lines that he and his family used to drive cattle on.

Later, Hamilton sought his fortunes in the cattle and ranching industry in the wake of the Dust Bowl. For decades, the short grass prairies of western Oklahoma had produced bountiful harvests of wheat and other agricultural products. Yet severe drought in the 1920s combined with the economic collapse of the Great Depression had driven many farmers off their land in what had once been known as the Great American Desert.

Hamilton and his brother partnered with a financier in Woodward County, Oklahoma to reclaim some of these abandoned properties and raise cattle.

“We scrounged up the old fence lines and got some land fenced, and our partner financed 300 steers for us,” he said.

Though the land’s traditional short grasses were unsuitable for farming operations that required annual tilling, it was perfect grazing country for cattle operations.

“That country should have never been plowed,” stated Hamilton. “Some of the old fields were still blowing (away), but a lot of them had grassed over somewhat. Our partner furnished the cattle, and we furnished the grass, and we split the profits. We’d just gotten started on that when Pearl Harbor happened.”

The war

The war

Hamilton was one of the first to volunteer in the aftermath of the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941, despite being qualified for an agricultural draft exemption.

“I volunteered for it, I wanted to go,” said Hamilton.

Following a battery of interviews and examinations, he was sent to Uvalde, Texas as a member of the cadet flying corps. Upon his completion of the primary training school, he had training stints at Randolph Air Force Base – then part of the U.S. Army Air Corps – and Mission, Texas. He completed his domestic training in Florida at fighter school before being deployed to the North African theater.

Hamilton concedes he’d never flown before he joined the service, but as he said with a grin, “I wanted a fighter plane.”

He attributes his interest partly to the publicity of units like the First American Volunteer Group, nicknamed “The Flying Tigers,” comprised of American pilots serving in the Chinese Air Force before the U.S.’ entrance into the war.

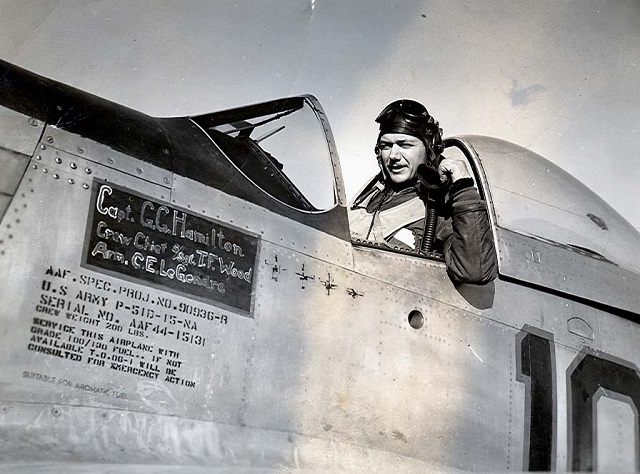

Hamilton flew a P-40 fighter plane in North Africa, before moving on to the P-47, an upgrade in military technology that he referred to as“a whole new world.”As a member of the 317th and later the 325th fighter groups, nicknamed Checkertail Clan for their distinctive look, he took part in combat missions supporting the invasion of Sicily, including bombing runs on German air bases on the island of Sardinia. Once in the P-47s, his unit’s mission almost centrally focused on escorting heavy bombers.

“When they finally got enough real estate in Italy to build airfields, we went there and started really flying with the big boys,” he said. “I finished my tour of 54 missions and came home, but I’d signed up to go back before I left, like a group out of our squadron.”

Upon his return to the European theater, Hamilton flew more combat and escort missions before being promoted to an operational officer posting. In that role, he was responsible for the planning and flying of missions into Nazi-controlled air space, a position he says he found extremely interesting due to his access to intelligence information. All told, Hamilton served the duration of the war.

“I was over there when it ended. I wanted to be. It was with a great group of guys and was an adventure of a lifetime that I thought would never happen again,” Hamilton said. “Of course that turned out wrong.”

Back in the U.S., Hamilton moved to Dallas on the advice of an aunt who helped him get started in the real estate business before returning to Woodward County to work the ranch.

Coming home

Hamilton’s Potawatomi lineage comes from his mother’s side; he is a descendant of the Burnett family.

“We were aware that we had an Indian background, and my mother’s mother was very traditional and still had some of the old beliefs and superstitions, so we knew that had Potawatomi blood.”

Another drought in the 1950s left land across Oklahoma unattended again. Hamilton’s ties to family in Pottawatomie County brought him closer to the CPN homelands as he bought up property for his agriculture operations. His background in ranching, combined with what he had learned in the real estate business with his aunt in Dallas, helped him succeed

“There were cases of absentee owners due to people having left for California and Oregon, or multiple owners on land, with no one owning more than 160 acres. It was very interesting to deal with, but piece by piece I’d put the land together.”

Speaking just a week before his 100th birthday, Hamilton said that in terms of thinking about his age, “there’s no difference at all. They just come on, one day at a time.”

Asked what advice he’d give his younger self, he refers to a principle that appears to have gotten him far in the past century.

“Just do what you say you’ll do, and do your best whether you’re working for yourself or for someone else. That’s the weakness and cause of failure for a lot of people that get into business for themselves and don’t push themselves like they should. For me, it almost never felt like work, because it’s what I liked doing.”

Update: Following the publication of this piece in the July 2016 edition of the Hownikan, George Hamilton walked on in March 2017.