When Meriwether Lewis encountered the Shoshone tribe in 1805 during the Lewis and Clark Expedition, he later wrote of the encounter, “The means I had of communicating with these people was by way of Drewyer [Drouillard] who understood perfectly the common language of jesticulations or signs which seems to be universally understood by all the Nations we have yet seen.”

Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL), also known as Plains Sign Talk and Hand Talk, has been used for centuries, and Peltier and Vieux family member Charles Scott hopes to bring it back to the Citizen Potawatomi Nation.

Scott first started researching PISL while taking a class with CPN Director of Language Justin Neely.

“He made a comment that you can’t really be Potawatomi unless you speak the language,” Scott said.

Scott’s own son-in-law is deaf, and though Scott’s grandchildren are hearing, they have learned sign language from an early age.

“I thought, ‘What if my grandson was deaf? He couldn’t be Potawatomi, because he would never speak.’ That just resonated with me,” he said. “I came across this Plains Indian Sign Language and started researching, and I found out that the Potawatomi, we’ve always used sign language.”

History of PISL

According to Start ASL, an online resource for learning American Sign Language, “Some experts believe that early humans used sign language long before spoken language evolved. Similarly, Native American tribes communicated using Hand Talk centuries before Europeans came to North America.”

Not only did it serve as a means of communication for Native Americans who were deaf or hard-of-hearing, but also assisted with conversations across cultures.

Starting with explorers in the 1400s, Europeans who came to the Americas described encountering an Indigenous sign language. Because there was no common language among the many Indigenous tribes, sign could act as a bridge across language barriers.

Several in the missionary and military fields studied and published information about the language, starting with Major Stephen L. Long in 1823, with several others to follow throughout the 19th century.

W.P. Clark with the U.S. Army was one of those asked to make a study of the language. In his book, The Indian Sign Language, which was published posthumously in 1885, he described being in command of individuals from about six different tribes around 1876.

“I had, of course, before known of the sign language used by our Indians, but here I was strongly impressed with its value and beauty,” he wrote. “I observed that these Indians, having different vocal languages, had no difficulty in communicating with each other, and held constant intercourse by means of gestures.”

Clark traveled across the United States and Canada with an interpreter, visiting several tribes, and he recorded the gestures used for various words, making note if there were differences from tribe to tribe.

“Although individuals may obscure the meaning of these gestures through carelessness, awkwardness, or efforts to secure a superabundance of graceful execution, yet one skilled in the sign language will instantly recognize them, provided that they possess the radical or essential part,” he wrote.

“While many dialects of Hand Talk exist, the language is essentially universal,” the Start ASL website said. “Two-thirds of the tribes in the United States have used it for centuries. This allowed an indigenous population that spoke more then 500 different dialects to communicate with one another.”

The website even goes on to say that Hand Talk in the 1800s influenced the development of American Sign Language.

“This influence came about in the 19th century through the signing of Native American children who attended the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut,” the website said.

Though it is estimated that 110,000 tribal members used PISL in the 1880s, the Start ASL website says that number had already dwindled to a fraction in the 1960s, and today, there are few active users.

“Like the other indigenous languages of North America, Native American Sign Language is endangered,” the website said.

Efforts to save PISL

At one time, efforts to document PISL were considered so important that an act of Congress supplied funding for a council.

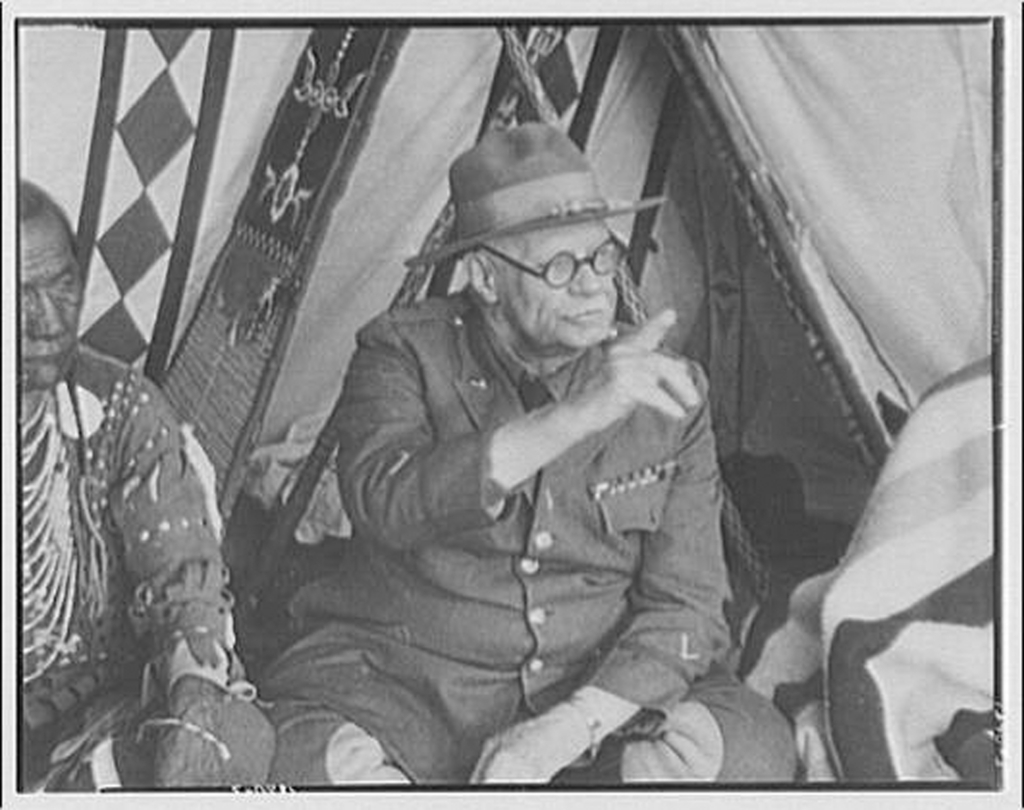

“In September of 1930, the largest gathering of intertribal indigenous leaders ever filmed was held with the goal of documenting and preserving American Indian Sign Language (AISL), sometimes also referred to as Hand Talk,” the National Park Service website said.

At the council, 18 official participants represented 12 different tribes and language groups.

The film, the website said, “illustrates how participants use this nonverbal-communication modality to express a wide range of ideas in a group whose diversity of spoken languages surely inhibited verbal communication.”

Today, efforts continue to revive PISL, and Scott said much of what they have to work with is the information gathered at that council and books written by Clark and by William Tompkins.

“There are a couple of sign language conferences coming up, and there are some sign language conferences that have happened in the recent past,” Scott said of efforts to revive the language. “There are more tribes starting to incorporate sign language.”

Right now, he said, those involved in the conferences are trying to standardize how PISL is taught, but also preserving the original signs.

“There’s always a tendency to make up a sign. We want to try to keep it pure with these books we have, the historical books,” Scott said.

Sign language as a bridge

Not only does Scott hope to bring back sign language as a way of preserving Potawatomi culture, but he also thinks it can be used as an aid to learning the Potawatomi language.

“When I met some of these other tribes from out west, they’re starting to incorporate sign language, and they’re revitalizing their language faster,” Scott said.

“At any given time, about 8 percent of the population is either deaf or hard-of-hearing,” Scott said. “That’s a lot of people, especially when you spread it out over 38,000, like for our Tribe. … If our goal was just to get 8 percent of our population to speak Potawatomi, sign language can do that.”

He thinks sign language could make the language more accessible, especially for Tribal members who are deaf or hard-of-hearing.

It’s a concept sometimes employed with other languages. There are multiple resources available for teaching babies and toddlers sign language, something they can pick up before learning speech. There have even been studies on sign language being used as a bridge to learn a new language.

A paper written by Sheryl Nicholson and Emily Graves, titled “Sign Language: an effective strategy to reduce the gap between English Language Learners’ native language and English,” explains that having a tangible sign to link two languages — for example the English word red and the Spanish word, rojo — offers a concrete connection to speakers.

“By providing students with a manual form of communication, the gap between the two languages can be narrowed,” they wrote. “Sign language does provide a tangible means to link two languages together. It does not matter what the two languages are since signing provides the connection between them.”

With so few first-language speakers of Potawatomi, and not many second-language learners who are fluent, Scott’s hope is that someday PISL could be incorporated into language classes, possibly resulting in a revival of both pieces of the Potawatomi culture.

“In the sign language community today, what we like to say is when we lost our language, the first thing we lost is sign,” Scott said.