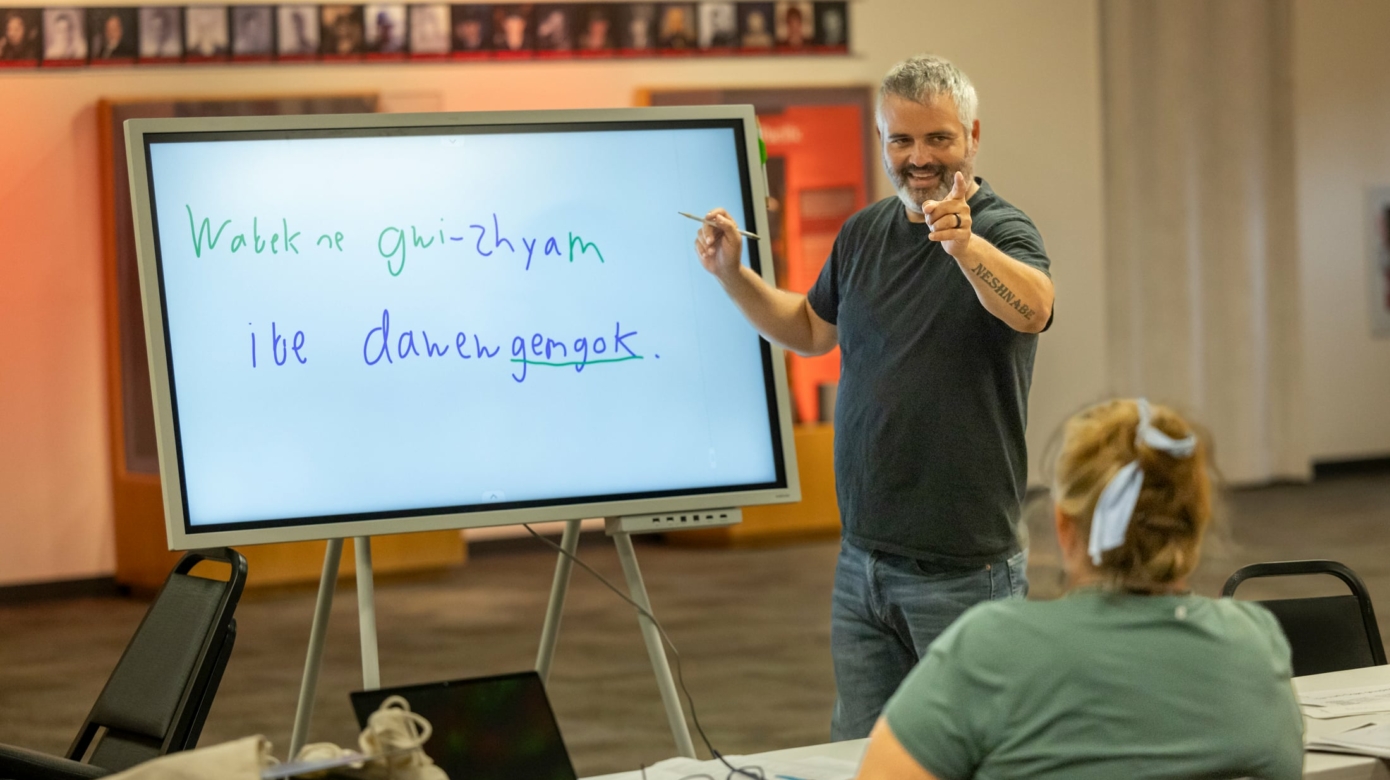

Fewer than five first-language Bodéwadmimwen (Potawatomi language) speakers are alive in North America. Citizen Potawatomi Language Department Director Justin Neely began working for the Tribe more than 15 years ago and took on a new challenge this summer to expand the number of fluent second-language speakers with help from The Endangered Language Fund.

CPN was one of four Native Voices Endowment grant recipients in 2022, which the department used to fund a summer master apprentice project in 2023. This is the first immersion program Neely has offered as a language teacher, and the grant helped pay for three students to study Bodéwadmimwen for eight hours, five days a week for eight weeks. One language department staff member also joined the group as well as a graduate student and two Tribal members eager to audit the class, making a total of seven students.

“I’m very, very proud of each of these individuals for taking the time and effort to try to learn. Because one thing that I think is the hardest to get is enough time with people,” Neely said.

Bridging gaps

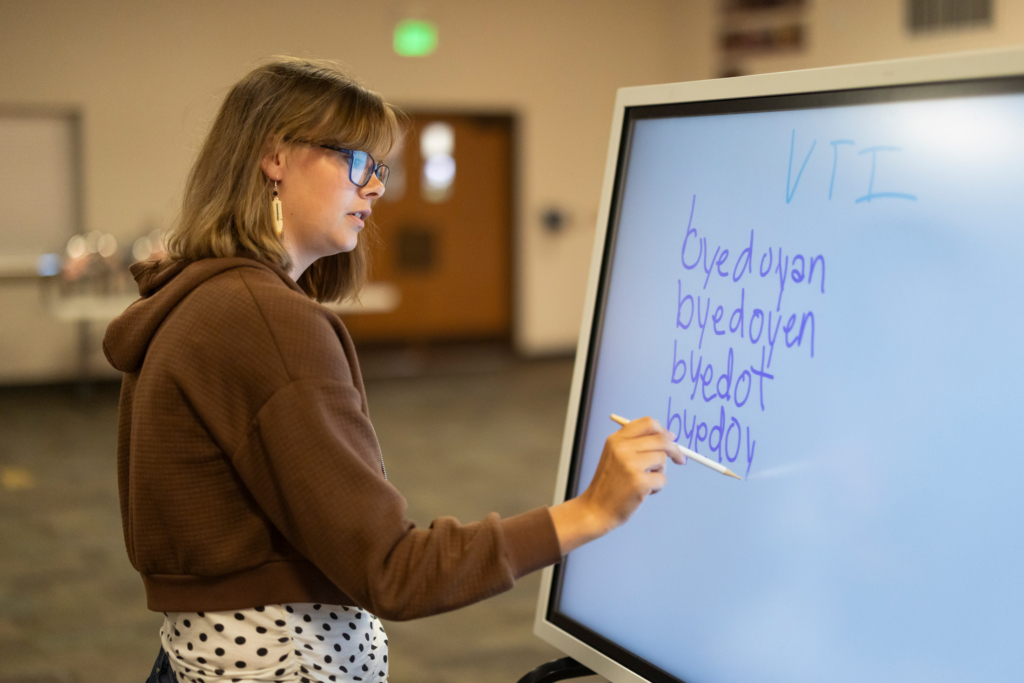

Lorrie Underwood came to CPN from Colorado for the program, which lasted from May 30 to July 21. She spent several years working on the language on her own but decided not to pass up the unique opportunity to immerse herself, despite the distance.

“It’s been an amazing program. I’ve met some amazing people, and I’m just very thankful that everything turned out the way that it did,” she said.

Marilyn Annanders has also been studying Bodéwadmimwen for the last few years, and when her granddaughter, Mikayla Paison, got accepted into the summer master program, she decided to audit the class alongside her.

“I’m trying to start a fire because I know I’m not (an expert), but here’s my ember,” she said, pointing to Paison.

It has brought them closer together and filled a generational divide. Paison had no experience and knew only three or four words Annanders had taught her when the program began.

“I figured I would delve a little bit deeper into (the language). I actually didn’t think I would actually get accepted into (the program), but I’m really, really glad that I did. And it’s definitely something I’m going to work on in the future as well,” she said.

Kansas University doctoral student Matt Biel worked hard to find funding to spend the summer in Oklahoma and participate. While he did not receive funds from the Endangered Language grant, he was able to travel with the help of his graduate studies program.

“Having gone to university and having mistakenly wandered into ancient history for a while where I had to do several languages, I can say … this has been a far better experience than any university, any other language learning process that I’ve gone through,” mostly because of the hands-on approach, he said.

Cultural connections

Tribal member Cole Rattan felt the call to learn the language and the Potawatomi culture as a young boy and into adulthood. He considers Bodéwadmimwen the basis for all other cultural practices, and the program has helped him progress further in his understanding than ever before.

“It’s almost like we’re doing our best to get as much as we can, and it’s eight weeks, but we’re going to, after this, be able to have a good handle on it moving forward. And I think everybody in this room is actually serious about learning the language,” he said.

All the students expanded their vocabularies and abilities to construct sentences, conjugate verbs and converse. They created group chats to send each other voice memos to speak the language. Having each other to practice with all day made the biggest difference in their progress, and they also took on cultural traditions together, including growing ceremonial sema (tobacco).

Rattan feels speaking the language is a spiritual act, and he put his skills to the test while caring for their medicines. Annanders recalled seeing his progress in the garden.

“We get down there to visit our sema and take care of it. And we said, ‘Well, we ought to say a prayer.’ And Cole says, ‘I can do that.’ And he did an amazing job, all in Potawatomi, and I felt like a proud peacock down there working with these two young ones because he did so good,” she said.

They all look forward to teaching future generations and spreading their knowledge amongst their family and friends. They saw the opportunity to spend eight weeks learning the language as contributing to something bigger than themselves, and Neely recognized that in his students as well.

“They’re putting all this effort in. They’re creating a language community for each other and for the future,” he said. “And the more folks that we can get to take that kind of level of commitment, will take the Tribe, will take us as Potawatomi people, far into the future.”

Find more learning opportunities from the CPN Language Department at cpn.news/language.