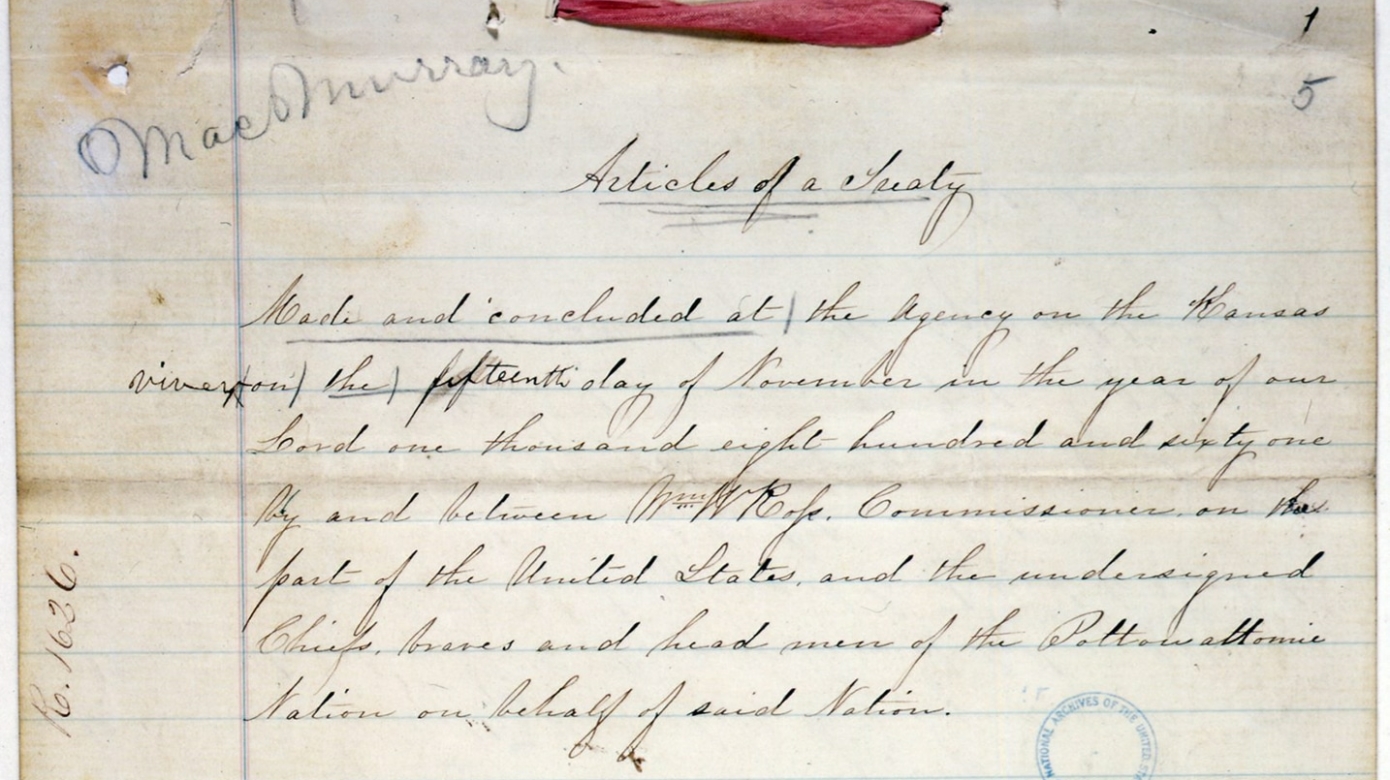

On Nov. 15, 1861, nearly 80 Potawatomi headmen and Tribal members gathered with federal officials to sign the Treaty of 1861. The agreement made 160 years ago created two separate Potawatomi tribes on the Kansas River Reservation, establishing the Citizen Potawatomi and Prairie Band. The former included approximately 75 percent of the 2,170 Potawatomi in Kansas. This group agreed to receive land allotments and the opportunity to become United States citizens. The latter chose to continue living communally within an 11-square-miles reservation.

“It is truly the foundation — our founding document. The treaty made us the distinct, sovereign nation that we are today. It set us down a separate path than our Potawatomi relatives,” said Dr. Kelli Mosteller, Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s Cultural Heritage Center director.

Kansas River Reservation

All the Potawatomi west of the Mississippi moved onto one reservation in northeast Kansas along the Kansas River in 1846.\

“We were promised that would be our home as long as the grass grew and the water flowed,” Dr. Mosteller said.

However, less than 10 years after arriving on the new reservation, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 established Kansas as a territory, which opened the area to non-Natives and land-hungry businesses.

“We had learned over and over again in our past that when more and more non-Native settlers came in — start to claim plots of land, establish businesses, start farms — the greed for Native-owned land would also grow,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Multiple forced removals, mounting pressure from the federal government, missionaries, industry and newcomers inspired Tribal members to look for potential avenues to increase permanency.

The Oregon Trail and westward expansion also brought violence, disease and alcohol through the reservation. While some Potawatomi built successful enterprises around the migration route, they also understood it symbolized great changes.

“One thing that is very clear is that all Potawatomi living on the Kansas River Reservation in the late 1850s very much felt that their continuation on that plot of land and their very lives were unstable,” Dr. Mosteller said.

The Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s founding members saw becoming landowners and U.S. citizens as potential solutions.

“Every time we were pushed out of the lands that we were living on, a group of non-Natives came behind us. And they had pieces of paper that legally say they own that land now. … The promise of having titles to our land … that is a strong promise, and when you’ve been cheated by the government and by the law over and over, thinking that you can get the law on your side, it’s hard to walk away from,” Dr. Mosteller said.

The founding members of the Prairie Band argued the federal government had not upheld any prior agreements, therefore they did not wish to make any more. As a result, two-thirds of the Kansas River Reservation was set aside for the Citizen Potawatomi and one-third for the Prairie Band.

“Neither one of them had a lot of confidence that what they were doing was going to play out to their advantage,” Dr. Mosteller said. “Our ancestors took a chance. It was a risk, but it was a calculated risk. And the treaty, as it was written, was not the treaty as it was actually applied.”

Quasi-citizen

Although the Treaty of 1861 established steps to becoming landowners and U.S. citizens, the process took time, and Tribal members were not able to obtain all benefits associated with normal citizenship, even after meeting all requirements.

To begin, a census recorded the number of Potawatomi and their standings. Land surveyors then separated the reservation, and Tribal members chose their allotments. Once settled, they had to apply for official land ownership.

“It wasn’t as simple as … how you or I would own land today. They had to petition, and they had to have the backing of their Indian agent to say that they were sufficiently adjusted and they were ‘civilized’ enough to own that land privately,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Once deemed “fit” to own the allotment, the treaty outlined that each member would receive a portion of the dollars from selling the excess lands, funds for purchasing farm equipment and seeds, and a two-year grace period on taxes as well as the ability to petition for U.S. citizenship.

“Unfortunately, that is not the process that was followed. Once people claimed their plots of land and were able to take their patents in fee simple, the State of Kansas — in total disregard for this treaty —immediately assessed taxes,” Dr. Mosteller said.

The taxation that occurred years before receiving any of the capital agreed upon in the treaty caused many to lose their allotments.

“It was absolutely done intentionally. … They ultimately wanted to sell that land to the railroad. They wanted to open it up for non-Native settlement,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Obtaining American citizenship also proved problematic.

“Not everyone became a U.S. citizen immediately. They had to have the backing of their Indian agent. … And just because you became a U.S. citizen did not mean you automatically had all the rights,” she added.

Those who received the Indian agent’s approval could be subject to American courts and taxation regimes, but they had limited voting capabilities and could not sit on a jury.

“We were referred to as quasi-citizens,” Dr. Mosteller explained. “It was a picking and choosing of what obligations of citizenship were applied and what protections of citizenship were not applied.”

Because of the negative consequences of the treaty and subsequent land-loss, the Citizen Potawatomi used a clause to sign another treaty with the federal government. The clause allowed the Tribe to sell some of the remaining lands in Kansas to purchase a new reservation in Indian Territory, present-day Oklahoma.

CPN continues to stand strong today as a result of the Treaty of 1861 and now has an annual economic impact of more than $500 million with more than 37,000 CPN members living across the United States.

Learn more about the Treaty of 1861 and this pivotal era in the Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s history by visiting potawatomiheritage.com.