June is Men’s Health Month. Mental health often goes undiscussed but remains an essential part of holistic care and quality of life. While Native Americans hold a higher rate of heart disease and various kinds of cancer than non-Hispanic whites, suicide and depression rates are higher, too, particularly among young men.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide rates for Indigenous men increased 71 percent between 1999 and 2017. Citizen Potawatomi Nation Behavioral Health Counselor Ray Tainpeah believes community and counseling lie as the keys to success when dealing with trauma.

“Oftentimes, particularly in the Native American community, with the suicide prevalence being high, there’s issues that have to deal with post-traumatic stress disorder. And so with all the pain that comes with that, counseling and therapy can explore those things in a safe way where people are open to be able to talk about those things,” he said.

Access to mental health services presents a barrier when attempting to treat mental health disorders; however, CPN Health Services prioritizes it and offers various resources to match individual situations. Men sometimes feel apprehension when beginning counseling but find it helps after giving it a chance.

“During the intake, it’s just exploring their life situations and life experiences and getting to know them,” Tainpeah said. “And when they feel like they’re comfortable with a counselor or a therapist, they’re more willing to come back. And as they build rapport with their counselor or their therapist, then they feel a little bit more safe to talk about those sensitive issues.”

Togetherness as healing

Many Indigenous ceremonies and cultural activities center around togetherness. CPN tribal member Randy Bazhaw feels restored and rejuvenated physically and mentally after a sweat lodge or drumming with others.

“To be in that sweat praying with one another, singing with one another, really letting your heart out and your pain out is an incredibly vulnerable position to be in, especially in what our society historically has said a man should do and say,” he said.

Tainpeah knows the power of group therapy, especially for addictive behaviors, and he often suggests it to his clients. Tainpeah calls the ideas and experiences shared in those groups “collective wisdom.”

“Through the process of sharing their life stories, they can relate to each other and can connect to each other and come up with some solutions that’ll help them to be a better dad, to be a better husband. … It works to benefit each individual when they are able to share with one another about how they’re coping and what they’re doing to change in order to improve their quality of life,” he said.

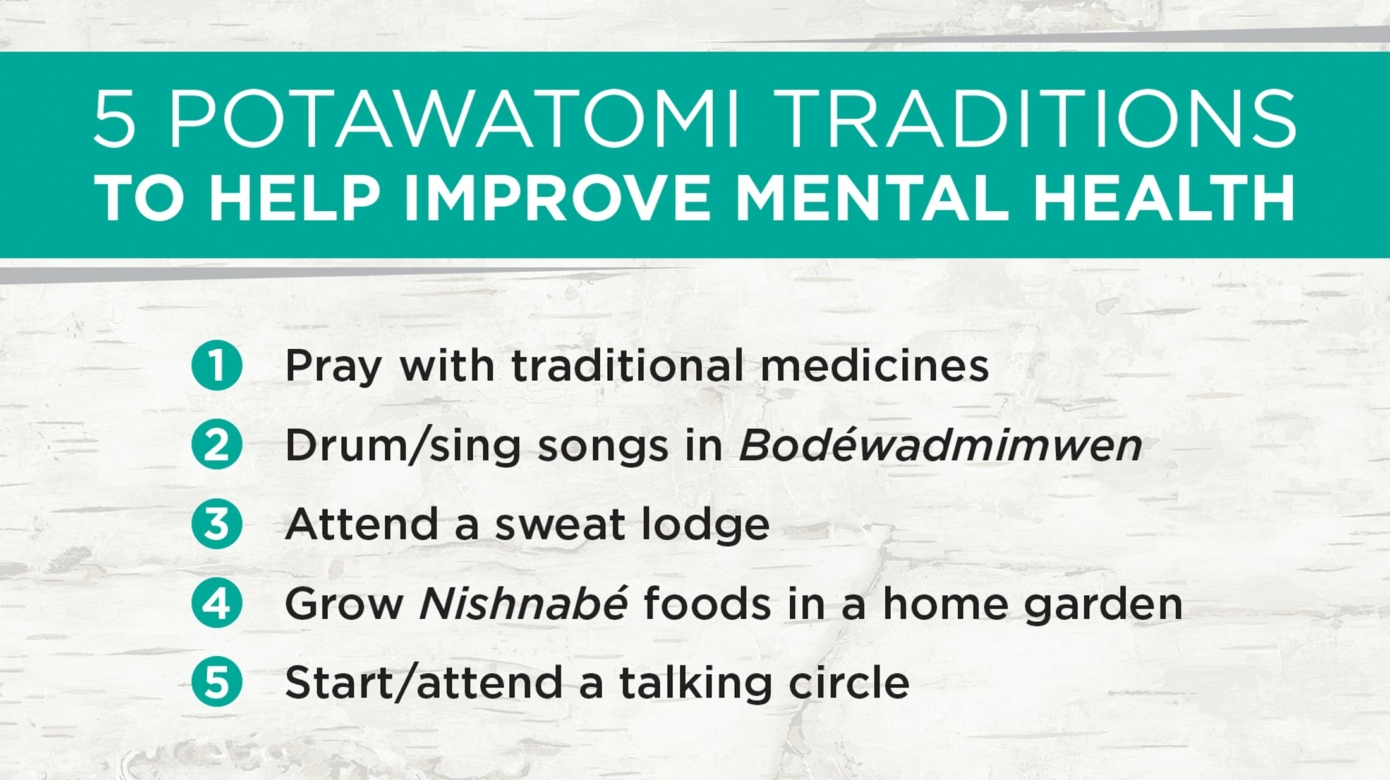

Traditions as growth

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recommends providers help their Indigenous clients maintain their cultural connections, especially to prevent and treat substance abuse and mental disorders.

“Through reconnection to American Indian and Alaska Native communities and traditional healing practices, an individual may reclaim the strengths inherent in traditional teachings, practices, and beliefs and begin to walk in balance and harmony,” the administration said.

Tainpeah also encourages clients to explore their heritage and culture to express their emotions, which often presents a struggle for male clients.

“When they go and reconnect or connect for the first time, there’s a sense of belonging, a sense of pride, and especially when they begin to participate, whether it’s the ceremonial grounds of the Eastern tribes or getting involved in a drum group or beginning the early stages of dancing in the powwow circles,” he said.

Bazhaw considers himself an outgoing person. He missed connecting with others during the pandemic, particularly opportunities to engage with and learn about CPN traditions in person with other Tribal members. Bazhaw turned to some traditional Potawatomi ways to cleanse his space as well as connect with segmekwé (Mother Earth) and his identity as an Indigenous person. He moved to Oklahoma at the beginning of 2020 to be closer to the Tribe, and the coronavirus kept everyone at a distance.

“Thankfully, I was just like, ‘Oh, well, why don’t I just bring out some of my medicines, like sage and tobacco, and just have a little smudge right there in my apartment?’” he said. “And having that connection and knowing that whenever I burned the sage and prayed with the tobacco, I’m connecting with these traditions that can still bring me and re-center me to the fact that I know I’m Potawatomi, and this is a part of me.”

Despite increased suicide rates and prevalence of anxiety, depression and other mental health conditions among Native American men, Tainpeah sees improvement for the future as society accepts fathers, sons, uncles and others openly discussing their problems and emotions.

“I think there’s been a lot of exposure for men to see, both in the media and in the tribal agencies (and) services, that allows them to think differently about their well-being — not just your physical well-being, but with mental health well-being. And hopefully, it allows them to be more willing to get help when they need it,” he said.

For more information about Citizen Potawatomi Nation Behavioral Health, visit cpn.news/CPNBH or call 405-214-5101. Find the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255 or suicidepreventionlifeline.org.