The National Congress of American Indians typically passes resolutions intended to shape policy for the millions of Indigenous people and more than 500 tribal governments in the United States. At this year’s NCAI Gathering, held just days after the U.S. presidential election, NCAI passed a resolution calling on the incoming Biden administration to name the “first American Indian or Alaska Native in our nation’s history to serve as the Secretary of the Interior.”

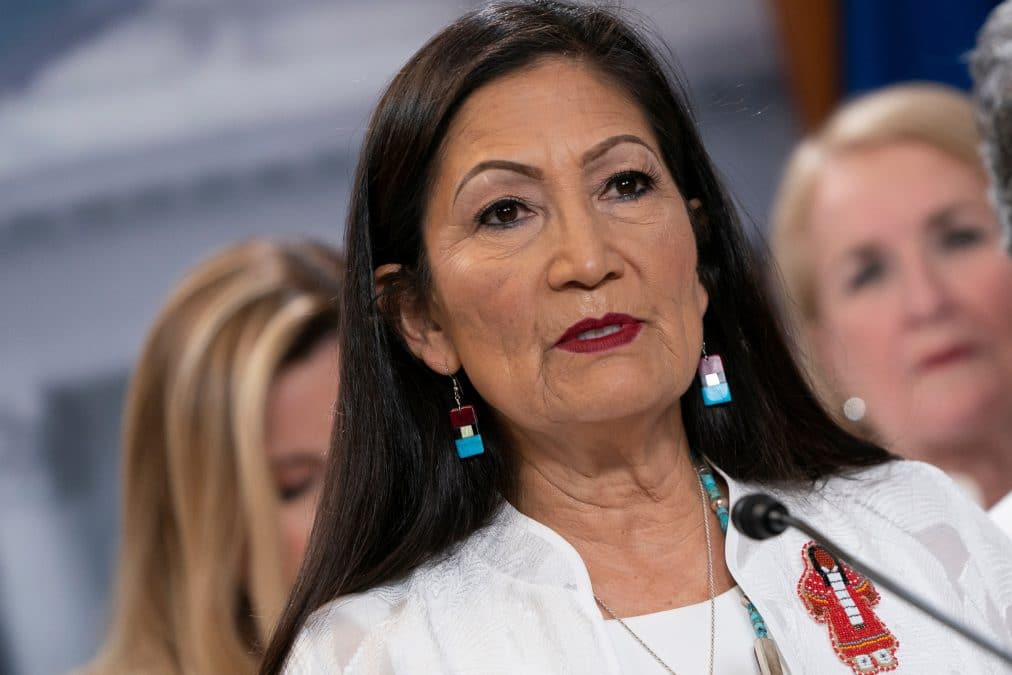

The administration’s choice of Congresswoman Deb Haaland (D-NM) was historic in terms of nominating an enrolled tribal citizen to a full cabinet position. If confirmed by the Senate, the Laguna Pueblo citizen would be the first Native American to lead the U.S. Department of the Interior. As head of Interior, Haaland will manage a wide portfolio over numerous agencies. The approximately 70,000 staff under the DOI oversee one-fifth of all the land in the United States. This includes managing national parks, wildlife refuges and natural resources such as gas, oil and water in addition to 574 federally-recognized tribal nations across 35 states.

Haaland would be the highest-ranking federal official with tribal citizenship since Charles Curtis. Vice president under Herbert Hoover, Curtis was a citizen of the Kaw Nation, originally from Kansas.

While the Trump Administration focused on rolling back restrictions on energy development on public and tribal lands, the incoming Democratic administration is charting a demonstrably different course. One of President Joe Biden’s first executive actions halted the Keystone Pipeline Project, which was the site of major Indigenous rights and environmental protests from 2016-17. Haaland has identified the restoration of public lands protections for Bear Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante in Utah that the Trump administration removed to support energy projects. Several tribes in southern Utah view the sites as sacred and claim the previous administration ignored tribal consultation procedures before trimming back protections. In addition to the nomination, President Biden pledged to reinstate the White House Tribal Nations Conference — a convening of tribal and federal leaders begun during the Obama Administration. It was not held the previous four years.

Haaland was overwhelmingly endorsed by Oklahoma’s Indian Country leadership. In mid-January, 25 tribal leaders, including CPN Tribal Chairman John “Rocky” Barrett, signed a letter to senators James Lankford (R-OK) and Jim Inhofe (R-OK) supporting her nomination.

The letter stated, “As senators for a state with 39 federally recognized Tribal nations and one of the highest Native populations in the United States, you fully recognize the importance of including Native representation at the highest levels of government. Native voices bring unique perspectives to vital discussions, and more often than not have a deeper understanding of the way federal initiatives impact Tribal citizens and Tribal governments.

“Rep. Haaland is not only a historic pick — she is the right pick for this position.”

A different background

Haaland was raised in Pueblo Laguna, located about 50 miles west of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Like many tribal lands rich in mineral deposits tied to uranium mining, Pueblo Laguna is located near the Jackpile-Paguate Uranium Mine superfund site. The high rates of cancer and health care issues tied to sites like it throughout the southwest influenced Haaland’s view on environmental stewardship. In 2016, she traveled to the Standing Rock, where tribal and environmental activists set up camps to protest the Dakota Access Pipeline’s path through Sioux territory in South Dakota. She stayed at the camp for nearly a week, helping cook and feed the protestors.

Haaland’s nomination financial disclosure forms indicate a background humbler than many of her contemporaries in Washington D.C.’s halls of power. According to Politico, while cabinet officials are often among the richest 1 percent of Americans, Haaland is a mold breaker in another way. She does not have a checking account with more than $5,000 and carries between $15,001 and $50,000 in student loan debt. She also has no income beyond her $174,000 congressional salary and $175 in annual payments from her tribe.

In an interview with Roll Call in 2019, Haaland recalled struggling to afford housing and holiday meals as a single mother. Her difficulties qualifying for government assistance programs and accruing student debt drove her to want to improve the livelihood of others.

Many in Indian Country hope that Haaland can represent the experiences many Americans far outside the beltway endure while shaping policy in Washington.