Communities across the world have passed down stories and beliefs tied to the cosmos. The Potawatomi hold their own oral traditions linked to astronomy, and learning about these customs ensures teachings survive for generations to come while simultaneously creating a sense of balance between the past, present and future.

“The fact of the matter is, a lot of us grow up not speaking our language, not knowing our history and knowing very little about our culture. … This is a really common story for, I think, a lot of Potawatomi people,” said Blaire Topash-Caldwell, citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians.

Learning traditional knowledge and customs through the stars helps remove the separation sometimes created between modern living and being Native American, she added.

“I see this connection between constellations and Indigenous astronomy as saying, ‘Hey, our ancestors were scientists. I don’t have to put my Indigeneity on the back burner in order to be a professional or to be an astronomer. They’re not separate things,’” Topash-Caldwell said.

Lowered down

Scientists and astronomers like Neil deGrasse Tyson recognize that humans contain the same genetic makeup as the stars.

“Even though we’re talking about stars and suns that are millions of miles away, and sometimes millions of light-years away, that doesn’t make it any more separate from us,” Topash-Caldwell explained. “I bring it back to a sort of Anishnabe perspective, which we see everything like we’re related. … We see everything in a kinship relationship. The stars are in our kinship. They’re the star nation.”

She began learning more about Potawatomi star knowledge during her time working in the Pokagon’s archives under the department of language and culture. During a Zoom interview with the Hownikan, Topash-Caldwell highlighted how the word Nishnabé can create ties to the skies above.

“Depending on what community you’re from, (Nishnabé) literally refers to being low or being lowered down,” she said.

Potawatomi and other Nishnabé believe that plants, animals and other living beings have more wisdom and are more important than humans.

“It’s a really humbling sort of explanation, but the other explanation that I get a lot is that Anishnabe, the Ones Who are Lowered Down, refers to our creation story that we were lowered down from the sky realm, specifically the hole in the sky constellation that the Ojibwe call Pugonakeshig,” she said.

The Potawatomi, Ojibwe and Odawa are brother tribes, and at one time, were one single tribe. Because of this, the languages and culture across all three are similar. However, most Potawatomi call Pugonakeshig constellation Mdodosenik (Sweat Rocks).

Guidance

During the Nishnabé people’s migration from the east coast to the Great Lakes region, some Tribal elders and history keepers believe they followed the celestial phenomenon known as the Crab Nebula supernova explosion.

“It left a really bright point in the sky (that) was definitely observable at night, but it was so bright you could see (it) during the day as well,” Topash-Caldwell said during a 2020 Potawatomi Virtual Gathering presentation.

Additionally, Potawatomi constellations describe seasonal activities. Some communities believe that it is appropriate to share winter stories only when Pondésé Nëgos (Winter Maker) is in the sky.

“Some people have the interpretation that rather than reserving certain stories for winter, or more specifically when snow is on the ground, that actually (Pondésé Nëgos) might have been one way … to communicate that what we really need to do is reserve the stories for when Winter Maker is in the sky,” she said.

The stars vary depending upon location and time of year and may hold warnings and other communications. Through research and studies, Topash-Caldwell said she agrees with Carl Gawboy, an Anishinaabé artist from the Bois Forte Reservation in Minnesota, about the Nambezho Nëgos (Underwater Panther Star). It becomes visible between late winter and early spring when the water begins to melt and flow quickly, and he believes it could indicate the importance of employing extra caution when traveling by water.

“We know that nambezho (underwater panther) is a water spirit that we need to respect and that it’s associated with whirlpools and capsizing canoes … and (the nambezho petroglyphs) seem to show up in places in the Great Lakes where the water can be really dangerous,” she said.

Learning resources

Becoming more acquainted with Potawatomi star knowledge preserves an important part of Potawatomi culture, Topash-Caldwell said.

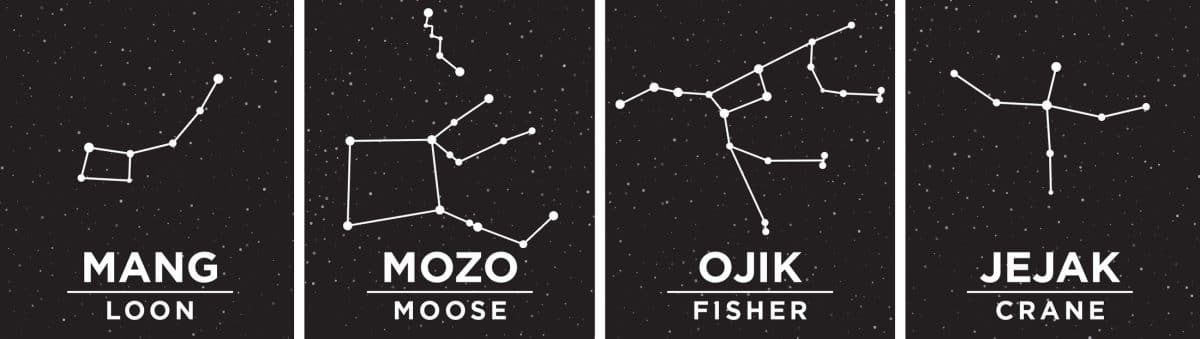

Kyle Malott, language specialist at the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, developed a map that features Potawatomi constellations based on the seasons, which is available at cpn.news/stars.

Topash-Caldwell also recommends using stellarium and the Potawatomi Constellation Star Map to help find Potawatomi constellations.

“It’s a free downloadable program where you can punch in a location anywhere on Earth, like in Oklahoma or here in Chicago, and you can get a 3D view of the night sky,” she said.

Stellarium automatically selects the current date, but Topash-Caldwell said users can choose other times of the year.

“And not only do they have the Greek/Roman constellations, they have the Ojibway ones pre-populated in there,” she said.

“There’s so much ancestral knowledge contained within (the stars) that we just don’t have access to. I think some communities will have stories that we can add as time goes on.”

The Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s Cultural Heritage Center also features a digital interactive that highlights Potawatomi constellations.

Topash-Caldwell encourages Potawatomi to utilize as many resources as possible to learn about Potawatomi constellations and to go look up at the stars every chance possible.

“Just get out there and do it,” she said. “Even though there is a lot of light pollution, you can still see a lot of the constellations.”

For more information on the CHC, visit potawatomiheritage.com.