By Lenzy Krehbiel-Burton

In hindsight, the signs were all there for Kristin Gentry.

A citizen of the Choctaw Nation currently living in Owasso, Oklahoma, Gentry had irregular menstrual cycles growing up, a family history of reproductive health issues, and despite being active and eating a moderately healthy diet, her weight would fluctuate wildly.

After multiple rounds of tests for allergies, diabetes and gastrointestinal issues, her doctors could not determine the culprit until she and her husband began attempting to have children. The verdict: polycystic ovary syndrome.

“We went to fertility specialist while we lived in New Mexico, and he showed me pictures of my ovaries,” Gentry said. “Apparently, I had multiple burst cysts — something that often requires an emergency room visit.”

‘It makes you feel like you’re not female’

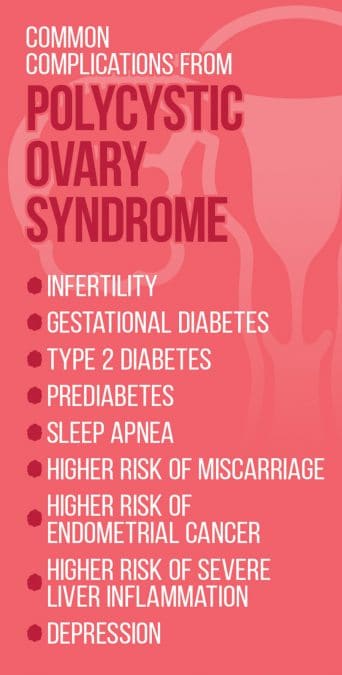

Although it is one of the most common causes of infertility, the exact cause of PCOS, or Stein-Leventhal Syndrome, is unknown. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, roughly 10 percent of women of childbearing age are impacted by PCOS with even higher rates estimated among Native American and Hispanic women.

A healthy ovary releases an egg on a regular basis. If the egg is fertilized, it can implant in the uterus and lead to pregnancy. If not, it is passed as part of a menstrual period.

In women who have PCOS, ovulation does not happen regularly, due in part to the development of numerous small fluid sacs, or cysts, on the ovary, which is often enlarged.

Additionally, excess levels of androgen, a male hormone, often impede ovulation in women who have PCOS. Those high levels also sometimes cause external signs visible to others, including excess facial hair, male pattern baldness and severe acne.

“It (the hormone imbalance) makes you feel like you’re not female,” Gentry said. “When I was diagnosed, it all made sense why I didn’t feel like a girl for so long.”

Gentry’s experience is not wholly unique. JoEtta Toppah, a Muscogee (Creek) attorney living in Coweta, Oklahoma, had several of the symptoms growing up, including irregular menstrual periods and severe acne. However, despite having an emergency laparoscopy done to address a burst ovarian cyst, the possibility of PCOS was not raised until she and her husband attempted to start a family.

“When I went to talk to a doctor about family planning, the first time she did some labs and mentioned polycystic ovarian syndrome to me for the first time,” Toppah said. “She explained some of the symptoms, and it was like all of a sudden a light went off, and there was finally some explanation to all the crazy hormonal, reproductive issues I had been having my whole life. It also explained why I was having trouble getting pregnant.”

The exact cause for the higher rates among Indigenous women is not known, but several common risk factors are more prevalent among Native American women, including obesity and insulin resistance.

Nationally, American Indians and Alaska Natives are more likely to be obese than their non-Native neighbors, as per the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health. An estimated 43 percent of all Native adults nationally and 15.9 percent of Native high schoolers are considered to be obese, compared to 28.5 percent of white adults and 12.4 percent of white teenagers.

The figures are similar in Oklahoma, with more than 40 percent of Native adults considered obese. Despite frequently exercising and eating a moderately healthy diet, the hormone imbalance shoved both Gentry and Toppah into that category.

“I’ve gained and lost more than 80 pounds over the years because of this,” Gentry said. “It’s not because I’m lazy, as there is more to it. The negativity that comes with other people’s perceptions about my size is hard to deal with, so please give us more grace when it comes to our weight.”

Insulin resistance is when the body does not property respond to insulin, thus making it difficult to properly absorb glucose from the blood. That in turn forces the pancreas to make even more insulin to get the job done. It can be managed, or even reversed, through diet and exercise.

Living with PCOS

With a cure specifically for the condition still elusive, doctors often treat the individual symptoms instead.

For women with the condition who are not attempting to conceive, hormonal birth control is often prescribed to help regulate menstrual cycles. Depending on the specific form used, it can also help address the androgen-induced acne and facial hair.

Although the Food and Drug Administration has not officially approved it as a PCOS medication, metformin, which is often used to treat Type 2 diabetes, frequently is prescribed to women with PCOS in an effort to lower androgen and blood sugar levels. If taken long enough, it can help restart and regulate ovulation, but as Toppah is experiencing, it does not address the noticeable side effects caused by excess androgen.

“I now have thick, coarse hairs growing on my chin and sideburns,” Toppah said. “I carry tweezers with me all the time to pluck those embarrassing hairs out, or sometimes I just use a razor and shave them. I’m extremely embarrassed when I’m talking to other individuals up close.”

Gentry previously took metformin but stopped because it constantly made her sick. In November, she underwent bariatric surgery in the hopes that the improved circulation from the weight loss would improve the chances of ovulating regularly.

As per a study published in 2012 in the World Journal of Diabetes, bariatric surgery improved the fertility rates for 69 of 110 obese women who underwent the procedure.

“Although surgery has both short and long-term risks, the potential benefits may be greater in these PCOS women than in older women who are already more advanced with respect to vascular disease,” wrote Michael Traub, one of the study’s authors. “Every woman with PCOS … deserves to at least be offered education and counseling regarding the role of bariatric surgery in reducing their illness.”

Even if the surgery helps alleviate some of the fertility issues tied to her PCOS symptoms, Gentry said she is not sure whether she and her husband will attempt to have a second child. Their daughter, Jewell, was born in spring 2016, after multiple PCOS-related fertility treatments and regular visits to two different doctors throughout the pregnancy.

“Emotionally, I’m just not sure I can handle another round,” she said.