Potawatomi women traditionally hold a special place in Tribal society, but translating these Indigenous ideals to European and American cultural practices has not proven a simple task. However, one Tribal member rose above Western European ideologies of women and leadership. Massaw, daughter of Potawatomi Chief Wassato and wife of a French-Canadian fur trader, held standings as a Tribal headman and prominent business owner in the Potawatomi village near Lake Keewawnay in Indiana.

Named in honor of the community’s leader Keewawnay, the community served as a key location to hold councils. After the Potawatomi removals west, settlers moved on the land and renamed it Bruce Lake.

“Her status in the community I think was a combination of things,” said Blake Norton, Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center curator. Massaw held a reputation as an intelligent businessperson and host, often entertaining dignitaries and others at her home.

“She may have been from an esteemed family, but she was the one who secured her place within powerful circles,” Norton added.

Most accounts describe Massaw as stoic and commerce-minded, and although women held an integral role within the Tribe, they rarely received invites to authorize treaties as a headman.

“It’s just speculation, but this may be why she was noted as a man on the first two treaties she signed,” Norton said. “Women did sign treaties, but this would come a couple of years later as more land was being sold and reserved.”

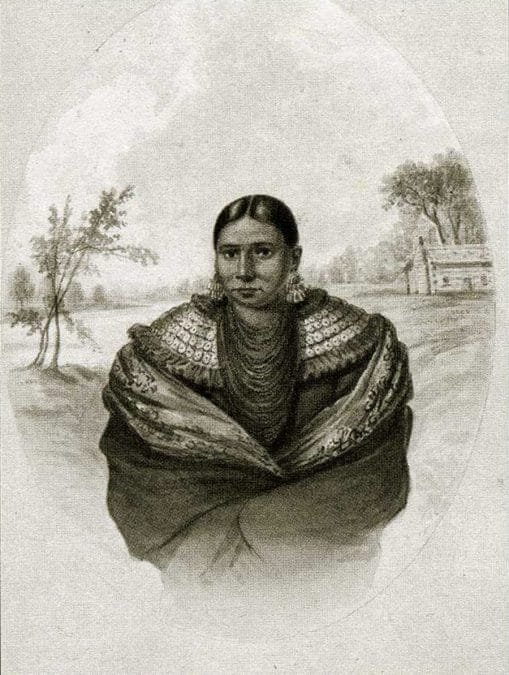

British artist George Winter sketched many Native Americans in the Great Lakes region including Massaw. He wrote in his journal about her status within the Keewawnay Village, including her large, two-story cabin that she often opened to dignitaries including U.S. military official Col. Abel Pepper, who held a reputation for securing treaties with the Potawatomi through unethical measures.

“During the time of the council, she derived considerable revenue from her accommodations, rude as they were,” Winter said. “Independent from the sources of profit from the officers of the government, there were many white men who were visitors to the Indian camp from mere curiosity who were glad to get entertainment at Massaw’s ‘Hotel de Foret.’”

Winter also discussed Massaw’s likeness in his diary, including her smooth, shiny dark hair; deep blue broadcloth blanket and petticoat with ribbon applique; silver brooches covering her cape; and her large, attention-grabbing earrings.

“The appointment of her dress were expensive, including her moccasins, which were neatly made and handsomely checkered on the ‘laces’ with ribbons of the primitive colors,” Winter wrote.

He also mentioned Massaw’s lack of homemaking skills, as “her prequesh-kin (bread) was not the best quality.” However, what cooking abilities she lacked she made up for with her cunningness to wage and win bets.

“Massaw had some civilized qualities of no mean pretensions,” Winter wrote. “She was in fact a gambler of no ordinary ability. She played euchre very well, and those who understand the game of ‘poker’ said that she was an adroit expert, often raking men of experience who attended her.”

Some of the U.S. officials Massaw hosted later forcibly removed her and the Potawatomi to lands west of the Mississippi on the Trail of Death. During the removal proceedings, her husband Andrew Goselin served as an interpreter.

Records of Massaw after the Trail of Death are scarce, but the information available indicates she continued to hold her Tribal standing.

“She is one of five women to sign the treaty of 1861,” Norton said. The document divided the Kansas Pottawattamie Reservation between the two Potawatomi communities in Kansas. The treaty allowed one to continue living communally and provided the other, Massaw’s group, land allotments and a path to potential U.S. citizenship.

“Her daughter Elizabeth married Jacob Vieux, son of Louis Vieux and Shanote (Charlotte) Chesaugan,” Norton said. “While living in Kansas, they took allotments and had three children. They later moved to Oklahoma and took allotments.”

After moving to Indian Territory, Massaw’s granddaughter Charlotte married Hiram Thorpe and had twin boys, Charlie and James (Jim).

“The boys were originally enrolled on the Citizen Potawatomi rolls at Sacred Heart, later removed and placed on the Sac and Fox rolls,” Norton explained.

Jim Thorpe gained worldwide attention as an athlete and the first Native American Olympic gold medal winner.

“Her other descendants became founding members of a new community in Oklahoma, successful business people, farmers, athletes, decorated veterans and members of Tribal government, to name a small distinguished few,” Norton said.

Visit the CPN Cultural Heritage Center’s West of the Mississippi gallery to learn more about Massaw, the various roles Potawatomi women played during this harsh era and how these ideals continue to drive CPN today.