Sculptor and Citizen Potawatomi Nation member Denny Haskew never chooses the easy path. Throughout his life, physically taxing experiences have both been a representation of, and carved out, his personality.

Now living in Loveland, Colorado, he is a longtime artist of Columbine Gallery and a member of the National Sculptors’ Guild. The consortium of carvers and casters assist in each other’s artistic endeavors and acquirement of steady work, mainly through commissions.

One of Haskew’s sculptures, Courage to Lead, sits in front of CPN’s Grand Casino Hotel & Resort. The piece depicts two Native American warriors shooting arrows into the sky while leaning back with their bodies brushing the earth. A traditional story of bravery was the source of inspiration, and Haskew treasures this statue’s location on Tribal land.

Before taking on the arts, he spent years with stints as a professional guide at Grand Canyon National Park and as a ski instructor in Park City, Utah, among other jobs. He also served in the Army, spending two years deployed during the Vietnam War.

Sculpting 101

Haskew wound up creating monumental bronze casts while considering something less taxing on his body.

Haskew recalled a visit to the inaugural Sculpture in the Park juried show and sale in 1984.

“My mom knew that I was messing around with wood carving and stuff, and so I came, and I saw sculpture for the first time with that show,” he said. “It was a lightbulb going off in your head. This is what I should do, and I stayed. I never went back.”

Haskew apprenticed for a year having never studied sculpture before. He entered five pieces in the next Sculpture in the Park and used the earnings to expand his portfolio. In the following years, he also worked with world-renowned Swedish sculptor Kent Ullberg, known for his massive casts of wildlife. Afterward, Haskew focused his career on large-scale representations of the human form with an emphasis on Native American imagery.

“I did a lot of shows, had a lot of galleries there for a long time. In my career right now, I’m down to about three galleries, and I do a couple of shows a year,” he said. “Pretty much do my large work on a commission basis.”

He works out of two studios: one with enough space for his larger pieces and the other, located in downtown Loveland, for smaller sculptures and paintings. Each statue begins with sketches before going through a series of techniques to achieve full size. Haskew sculpts in clay, and casts in bronze or bronze and sandstone.

“It has to be interesting from all the angles,” he said. “I’ve slowed down a bit, but it’s really physical,” he said. “You’re up and down ladders and putting on hundreds of pounds of clay, and it’s enjoyable.”

Pieces of history

Several tribes have commissioned Haskew for pieces representing a significant portion of their history or tell an important cultural story. In November, the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community unveiled a depiction of Chief Sakpe III, whom the U.S. government executed in 1865.

The tribe hired Haskew to restore the 12-foot-tall bronze sculpture, I Once Rode Free, which he had cast for the tribe’s casino. It now stands in downtown Shakopee, Minnesota.

“That was my depiction of him with his horse looking out over the landscape and saying, ‘I once rode free,’ and it kind of speaks to all Native Americans,” Haskew reminisced.

Culture through human form

The human figure also interests Haskew, and he often designs pieces featuring Native Americans in all kinds of poses. He embraced the challenge of accuracy early in his sculpting career, and the body remains one of his favorite subject matters.

The piece Transformation stands out to Haskew as an example. A Native American woman rests with her knees tucked under her. Her torso bends as she stretches her hands over her head, oversized butterflies perched on her palms.

“The butterfly is what transforms from a caterpillar into a butterfly,” he explained. “This is a statement for females saying that it’s beautiful to watch females in our society transform from the discrimination and things that they’ve experienced and hopefully, coming to a new and better thing, more beautiful.”

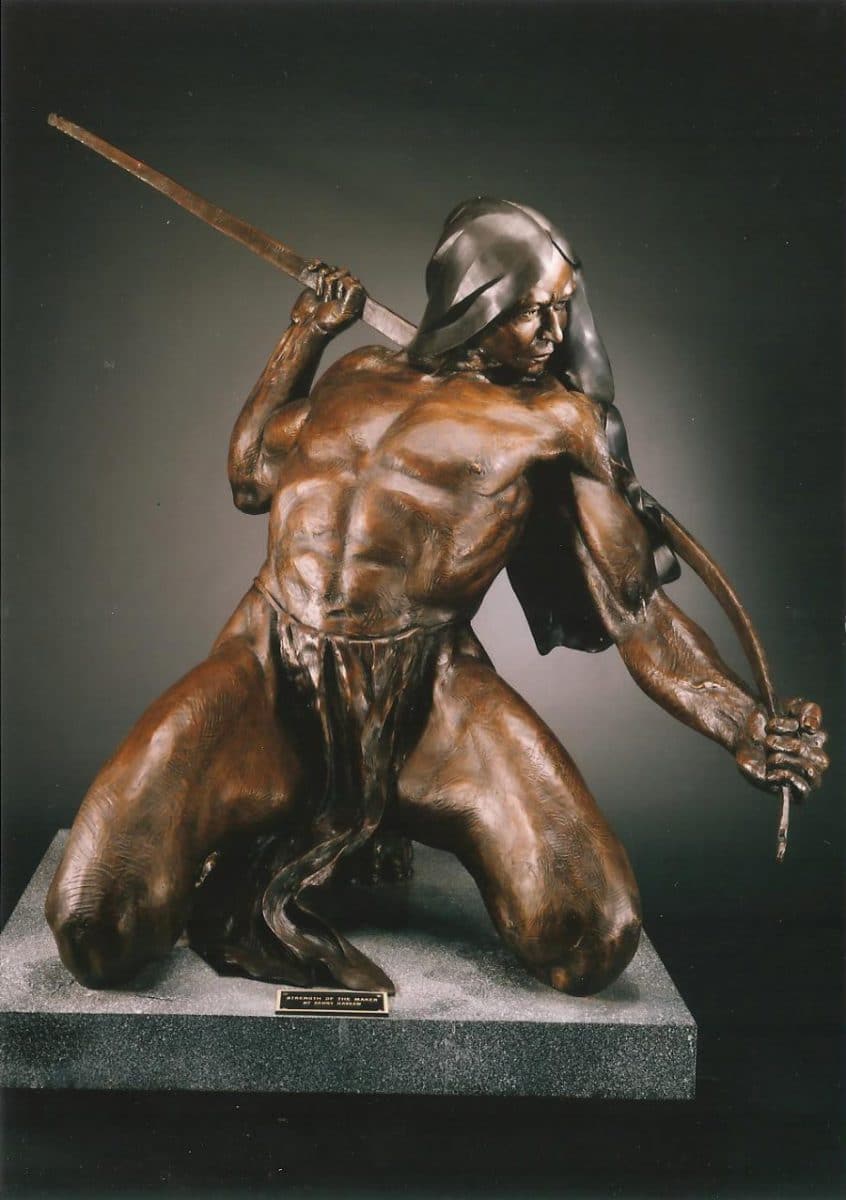

Haskew also explores the connection between Native Americans and nature. His piece Strength of the Maker won a show in Aspen, Colorado, and now sits in the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. It depicts a man testing the strength of his new bow across his back.

“What I’m trying to say is the strength of the Maker, the Creator, has created all of the picture. He has created the tree that the bow was fashioned from. He’s created this human,” Haskew said. “Nature is important to me, and I feel like humans are part of nature, and I didn’t see this in the piece, but obviously we need to be better at taking care of nature.”

Ancestry in bronze

The artistic ritual that Haskew practices, as he goes about assembling his statues, reminds him of his heritage; a process that is tedious, tough and trying, similar to his ancestors’ history to maintain — and even reclaim — their culture.

“I don’t think you can help but do that,” he said. “It’s interesting because, of course, most of the time it’s things that happened in the history in the past, but it’s also important to make it relevant to today. Have the message of the title show that this happened back then, but it’s still important that we recognize this.”

Haskew is descendant of the Pettifer family. Early in his career, he and his grandmother sat in his artist’s booth at Oklahoma City’s Red Earth Festival. People stopped by and commented on her beauty and her grandson’s creations.

“It was so fun to see her because she had spent, like a lot of our elders, most of her life trying to hide the fact that she was Native American,” he said. “It was a time when she could be proud at that moment, and I still get a little teared up when I talk about it.”

3 dimensions to 1

After sculpting for about 15 years, Haskew’s mother taught him to paint. She worked in her studio every day, guiding others and creating. He described her as very prolific. He took her classes and explored his style.

“The paintings are something I have a lot of fun with, and I experiment,” he said. “It’s hard to give me a style. I do like the impressionistic look, and I like to use lines. I enjoy using color sometimes. Sometimes, I’ll keep a solid color and draw all over it.”

His love of the human form carried over to painting, and sketching live models is a cherished part of the creative process. Haskew drew throughout his artistic career. Sculpting and sketching go together for him, especially training the hand and eye to communicate well.

The deeper connections with his grandmother and mother influence the projects he accepts and their subject matter. He takes pride in being Native American and the growth of CPN over recent decades.

“It’s been fun with the success of the Tribe to have the language come available to us, to have our history, to recognize the Trail of Death,” he said. “The great work they do with the eagle sanctuary, the naming ceremony — I mean to watch all of these things develop over the years, and we’ve been one of the fortunate tribes to have really good leadership, I believe.”

See more of Haskew’s work at haskewart.com.