In November 1861, a treaty signed by the U.S. government and Potawatomi tribal members officially established the Native Americans as a politically distinct tribe. This year marks the 155th anniversary of that designation.

“This is our origin story,” CPN Cultural Heritage Center Director Kelli Mosteller, Ph.D., said. “The census that followed that treaty is where we get our tribal rolls now.”

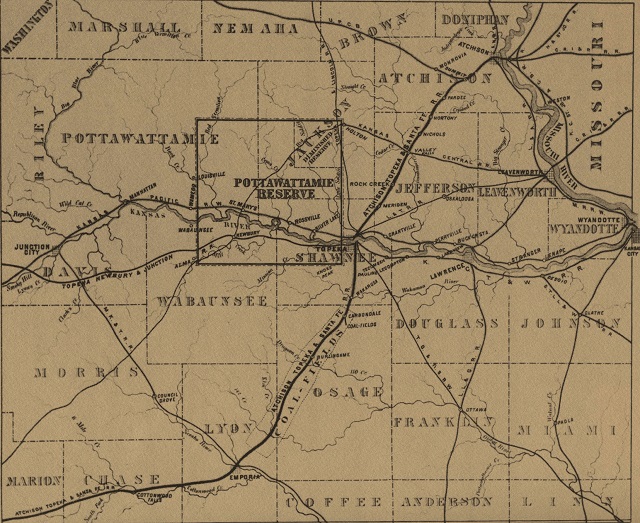

The federal government approached the Potawatomi with the treaty while they were living on a reservation in northeast Kansas. The essence of the document stated that instead of living communally in Kansas, they would be private land owners and United States’ citizens. They weren’t forced into signing the treaty or leaving the reservation, but a difficult decision faced the Potawatomi people at the time.

Two-thirds of those on the reservation opted to sign the treaty. Those people became the Citizen Band, and were able to negotiate how much land each tribal member received. Meanwhile, those who opted not to become American citizens became known as the Prairie Band and continued to hold their land communally.

“Our ancestors didn’t make this decision in a vacuum. They had undergone a lot of removals and trauma,” Mosteller said. “They were being told by their Indian agent that the government couldn’t promise that they would be able to stay on that reservation if they weren’t willing to sign and become land owners. They had seen several removals and made the difficult decision to do something legally and politically different than anything they’d tried before. By signing the treaty and choosing this option, they were attempting security for their families and taking control of their future during the uncertainty around them.”

This uncertainty involved other non-Native settlers moving to land all around them, the Civil War breaking out a few months earlier and the government’s unwillingness to promise they wouldn’t be removed again by force.

According to his descendant Jon Boursaw, Joseph Boursassa served on the five-member business committee which negotiated the treaty and was listed on the treaty as the official U.S. interpreter. He also negotiated with the Prairie Band Potawatomi to be part of the allotment process, but was unsuccessful, as they chose not to sign the treaty.

“One always takes pride in knowing his ancestry was instrumental in the history of the tribe,” said Boursaw, who followed in Boursassa’s footsteps by serving as CPN’s current District 4 legislator. “Along with the 1861 Treaty, Joseph was influential as a member of the business committee in negotiating our last treaty in 1867, allowing us to return our allotments and obtain land in Indian Territory, now Oklahoma.”

According to Mosteller, many promises were made about what it meant to be a citizen and a land owner. CPN members were told they would have rights and more control of their futures if they negotiated the treaty. Many of the Potawatomi signed the Treaty of 1861 simply because they didn’t want to be forcibly removed again.

After the treaty was signed, the U.S. government failed to follow through with many of the promises which were in the document, that they would first have a census, survey the land and allow tribal members to choose which plot they wanted. Tribal members were supposed to receive money to buy seed and farming equipment to have two full seasons of crop production as a means of income. After those two years, the government would determine who was worthy and eligible to be U.S. citizens, and those ready for citizenship would be taxed.

According to Mosteller, that’s not how it played out. They were taxed almost immediately, but had no source of income and therefore couldn’t pay. The federal government took the land of those people who failed to pay their taxes.

“The intent of the U.S. government was that the allotment process would bring an end to the Indian reservations and make it easier to integrate the Native Americans into the ways of the white man,” Boursaw said.

According to Boursaw, six years later, CPN negotiated the Treaty of 1867, which allowed tribal members to return their allotments to the federal government, which were then sold to the Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad Company.

The proceeds were used to purchase CPN’s land in Indian Territory and the migration of tribal members to present-day Oklahoma began in the 1870s.