Aug. 29 marks the 1821 Treaty of Chicago’s 200th anniversary. The agreement between the United States, Ottawa, Chippewa and Potawatomi included the cessation of almost 4 million acres of Native land and forever impacted the tribes’ hold in the Great Lakes region.

Reservation treaties, like the 1821 Treaty of Chicago, strove to separate Natives from non-Natives to make certain areas more enticing to settlers. Federal, state and territorial officials consolidated and obtained tribal properties for non-Natives moving into the Great Lakes region.

“The federal government started to talk about the ‘Indian problem’ during this period, and the ‘Indian problem’ is essentially, ‘What do we do with Native Americans who have been living on lands that we want to occupy?’” said Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s Cultural Heritage Center’s Director, Dr. Kelli Mosteller.

Negotiations

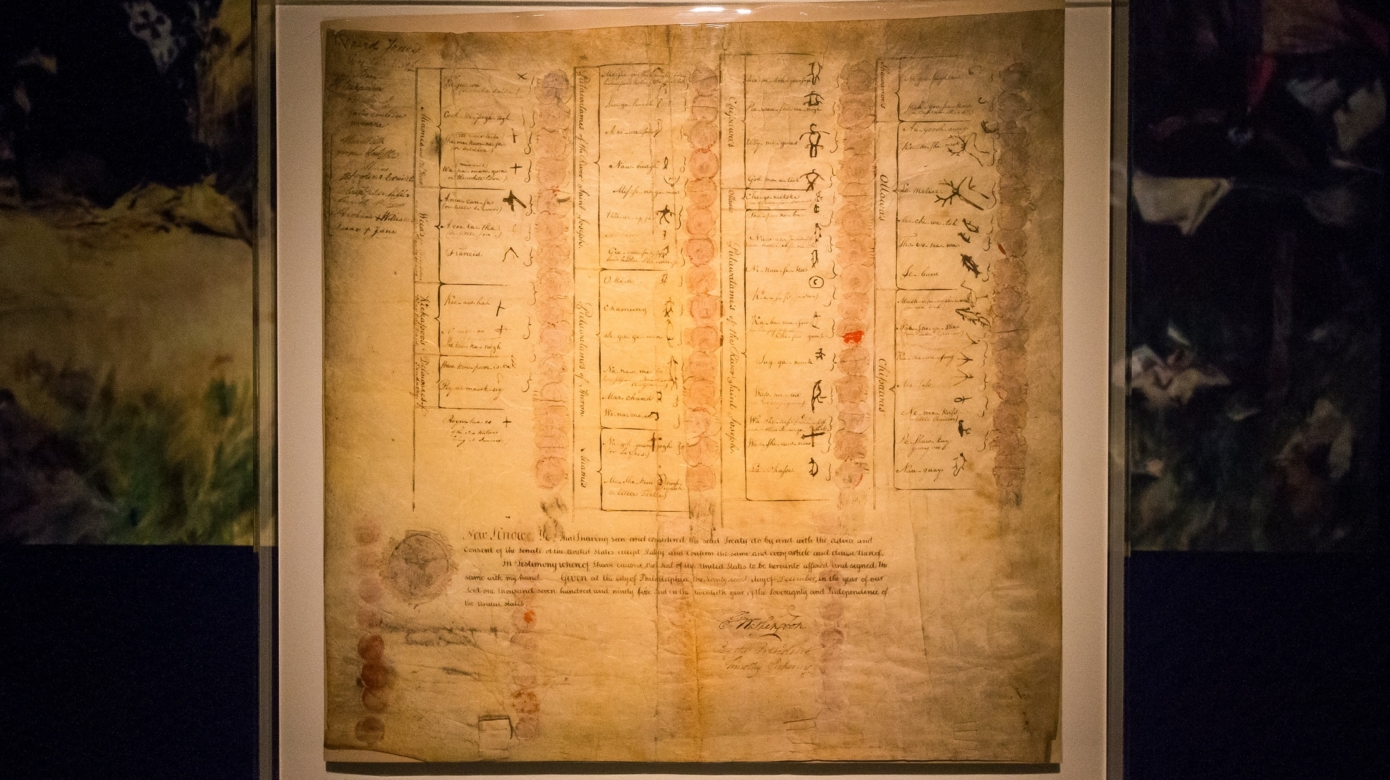

In mid-August 1821, approximately 3,000 Potawatomi, Ottawa and Chippewa gathered in Chicago to discuss land ownership with U.S. officials, including commissioners Lewis Cass and Solomon Sibley.

While the Potawatomi agreed to land cessations in the past, the amount debated in the 1821 Treaty of Chicago concerned many Tribal members. Discussions lasted two weeks, and during that time, Cass attempted to sway opinions with threats and withholding whiskey until Tribal leaders signed the agreement.

According to The Potawatomis: Keepers of the Fire by David Edmunds, “Cass would not accept the Potawatomi refusal and warned the Saint Joseph tribesmen that the remainder of the trade goods would be distributed only to the other Potawatomis if the Saint Joseph leaders continued in the recalcitrance.”

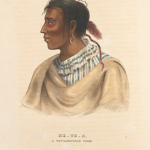

With a reputation as a warrior, spiritualist and orator, Potawatomi Chief Metea served as a spokesman for the Tribe on many occasions. He made one of his most famous speeches during the negotiations.

Chief Metea said, in part, “Our country was given to us by the Great Spirit, who gave it to us to hunt upon, to make our cornfields upon, to live upon, and to make down our beds upon when we die. And he would never forgive us, should we bargain it away. When you first spoke to us for lands at St. Mary’s, we said we had a little, and agreed to sell you a piece of it; but we told you we could spare no more. Now you ask us again. You are never satisfied! We have sold you a great tract of land already; but it is not enough! We sold it to you for the benefit of your children, to farm and to live upon. We have now but little left. We shall want it all for ourselves. We know not how long we may live, and we wish to have some lands for our children to hunt upon. You are gradually taking away our hunting-grounds. Your children are driving us before them. We are growing uneasy. What lands you have, you may retain forever; but we shall sell no more.”

However, Metea’s address did not provide the results he had hoped. Growing internal pressures and large promises made by the U.S. officials caused the Potawatomi to eventually accept the offer.

The agreement resulted in the Potawatomi relinquishing control of lands in southwestern Michigan up to the Grand River and a swath of land across northern Indiana from South Bend to the Ohio-state line. It established small reservational boundaries in return for annuities and resources and set aside acres for each of the Tribal signatories. Eventually, a second Treaty of Chicago in 1833 provided the groundwork for the Tribe’s removal westward.

Learn more about the 1821 Treaty of Chicago by touring the Cultural Heritage Center’s gallery Words & Leaders That Shaped Our Nation in person or online at potawatomiheritage.com.