Editors Note: On Sept. 20, 2021, the City of Shawnee formally de-annexed the land south of the North Canadian River. The detachment ended the legal dispute between the City of Shawnee and Citizen Potawatomi Nation. On Sept. 21, 2021, Leaders from the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and City of Shawnee announced Tuesday the launch of Shawnee Aligned, a new initiative wherein the two governments will seek opportunities to collaborate for the betterment of the Shawnee community. Read more here.

Editor’s note: On July 7, the Shawnee City Commission voted to move forward with a resolution that would amend the City’s Charter regarding de-annexation applications by property owners. The move was supported by a small majority on the Commission including Mayor Wes Mainord and Vice-Mayor James Harrod and was initiated by City Commissioner Keith Hall following the June 24 electoral loss of now lame duck City Commissioner Steve Smith, who is openly hostile to local tribes. The amended resolution, which will go on the ballot in November 2014, will make it more costly to property owners in the City who wish to petition for detachment. If successful, property owners who wish to detach from Shawnee will face the additional requirements, both financially and in terms of man hours, to make their case to the entire electorate of a city of 30,000 people instead their immediate neighbors who may agree on the detachment.

On top of being threatened by a City government who blatantly disregards established statutes of tribal sovereignty, property owners like the Citizen Potawatomi Nation have lost faith in the current regime’s ability to manage its municipal responsibilities following the flood at the CPN Cultural Heritage Center on March 31. The flood, caused by an uncapped water pipe owned and operated by the City of Shawnee, resulted in hundreds of thousands of dollars in structural damage to the Tribe’s museum. Unlike the common property owner, CPN’s own Roads Department maintains many streets south of the North Canadian River, including partnering with the City to pay for repaving of the Gordon Cooper Bridge in 2012.

The question remains, why shouldn’t property owners who live, work and take on the City’s responsibilities south of the river be able to collectively decide their future? Does the person on the other side of town have as good a grasp of the issues facing your street as your next door neighbor?

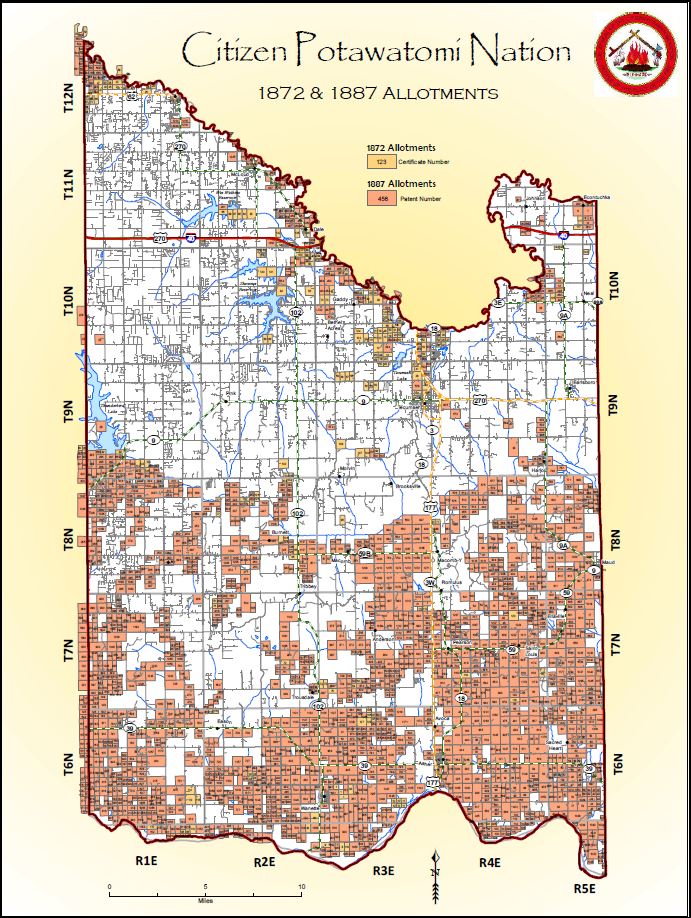

Upon further investigation into these issues, CPN delved into the original December 12, 1961 annexation of these properties by the City of Shawnee. The findings show that the original annexation of land south of the North Canadian River, much of which was allotted to tribal members as far back as the nineteenth century, was illegally annexed. The below article reports the findings of this research.

On February 27, 1867, dozens of Citizen Potawatomi Tribal members gathered on their reservation on the Kansas River and signed a treaty establishing the conditions for the Tribe’s removal from Kansas to Indian Territory. These headmen and other respected leaders were not strangers to displacement or dispossession. The Potawatomi were first removed from their ancestral homelands in the Great Lakes region in the 1830s to new territory west of the Mississippi River. Roughly a decade later they were again forced from lands the federal government promised would be their homes forever and moved to a new reservation in northeast Kansas. These experiences prepared the Citizen Potawatomi for the inevitable hardships that resulted from uprooting their families and starting over in a new place.

After signing the treaty, Tribal leaders and officials of the Office of Indian Affairs agreed that a delegation of Citizen Potawatomi would travel to Indian Territory and select a tract of land, not exceeding thirty square miles, which would become the Tribe’s new home. The treaty stipulated that the Tribe would buy the new reservation with proceeds from selling their “surplus” lands in Kansas.

In the winter of 1869 a group of Citizen Potawatomi traveled to Indian Territory and selected a tract of land in the center of the territory to become the site of the Citizen Potawatomi reservation. They ultimately paid $119,790 for the land. Tribal members had to save money to fund their own relocation and finalize their affairs in Kansas, so the earliest families to make the journey to their new reserve arrived in Indian Territory in 1872.

For almost twenty years the Citizen Potawatomi worked the land and struggled to survive and flourish in the challenging conditions of Indian Territory. In 1890, the federal government derailed those efforts by forcing the Citizen Potawatomi and other tribes in the area to participate in the allotment process, legislated by the Dawes Act of 1887. This act dictated that the Citizen Potawatomi accept individual allotments of land. Those lands that remained unallotted were then purchased at a rate far below the fair-market value and classified as “surplus” so it could be opened for non-Indian settlement.

On the morning of Tuesday, September 22, 1891, more than twenty thousand non-Indian settlers gathered on foot, horseback, and with wagons for the starting pistol of the Land Run of 1891. They hoped to claim one of the seven thousand available plots, each one hundred and sixty acres in size. At noon, the pistol fired.

More than half of the original 900 square mile Citizen Potawatomi reservation, approximately three hundred thousand acres, disappeared overnight. What had been legally purchased less than twenty-five years before was simply given away by the U.S. government.

For more than two centuries the Citizen Potawatomi Nation looked to restore the Tribe to the level of economic success it enjoyed prior to their forced removal from the Great Lakes region. After settling in Indian Territory and enduring the Land Run and Statehood era of government, Tribal leaders worked throughout the early twentieth century to reestablish the foundations of a Tribe that had been repeatedly abused by the federal government. However, by the 1960s, Citizen Potawatomi Nation leaders found themselves once again fighting for land which was promised to them by the United States.

In April of 1962, the business committee of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation approved a resolution on how to divide land that was being relinquished by the Bureau of Indian Affairs between CPN and the Absentee-Shawnee Tribe in Pottawatomie County. The land in question included the former Indian Sanatorium Hospital, and was being turned over to the tribes because the hospital had recently closed.

The resolution stated that the “tracts of land be designated as key tracts in connection with the socio-economic development program for the Citizen Band Potawatomi Indians of Oklahoma since these tracts are strategically located for the development of the Tribe.”

Citizen Potawatomi Nation struggled for another decade to establish and develop businesses. Ten years after that 1962 resolution, CPN was still limited to just $550 in a bank account and an abandoned BIA trailer serving as Tribal headquarters.

Following decades of forced assimilation and the termination of dozens of Tribal governments, the 1975 Indian Self Determination Act was passed by the U.S. Congress. This act allocated funds directly to tribes, giving them the authority to control their own welfare. By the late 1980s, the CPN began to flourish, fulfilling the resolution written two decades before.

Now, more than 50 years after the Citizen Potawatomi set out to use their land for the advancement of the Tribe and its people, investing millions of dollars in planned strategic growth, the government of the City of Shawnee is after the profit made by the Potawatomi.

Today, the City of Shawnee claims it annexed this land in 1961 through City Ordinance 156NS. However, they acted without regard for proper annexation procedures set out by state law and ignored meeting guidelines for the City. On December 12, 1961, the City Commission rushed an emergency hearing to vote on the annexation of lands around the Pottawatomie County Hospital. Commissioners were informed of the meeting, set for noon on December 13, 1961, between the hours of 4 p.m. and 5 p.m. the day before. Though all such meetings require 48 hours public notice, the Commission’s actions gave only 19 hours’ notice. According to the minutes of the proceedings, they made no attempt to post notice of the meeting publicly and made no effort to determine who were the rightful owners of the land and ask permission for the annexation, a binding legal requirement under state law. The Commission wanted to force the ordinance through with no debate, so the tribes were intentionally left in the dark.

The 1961 Oklahoma statutes on land annexation required that land either be annexed by petition, requested by land owners, or with written consent from three quarters of the land owners. They further stipulate that legal notice of the annexation must be published in local newspapers at least once for two successive weeks ahead of any meeting. The City of Shawnee Commission did not have written consent from either the Citizen Potawatomi Nation or the federal government, the two land owning parties. They only published one legal notice about the annexation, and it ran in the paper two days after they had already voted. In their haste, they acted illegally in order to gain control of the land legally held for Native American Tribes. The sole purpose of these actions by the City Commission was to profit from any future development of the land.

Also of note was the City Commission’s disregard for other standing legal principals when it comes to land annexation. Specifically, the Commission blatantly disregarded existing laws specifying that it was illegal to tax land that was annexed in parcels larger than 40 acres.

The land illegally annexed by way of City Ordinance 156NS encompassed two distinct parcels of land. The first parcel was owned by the federal government, while the other was owned by the Tribe. Despite this distinct difference in ownership the City of Shawnee claims to have annexed both with a single ordinance rather than following the proper procedures for each. {jb_quoteleft}”The land illegally annexed by way of City Ordinance 156NS encompassed two distinct parcels of land. The first parcel was owned by the federal government, while the other was owned by the Tribe. Despite this distinct difference in ownership the City of Shawnee claims to have annexed both with a single ordinance rather than following the proper procedures for each.{/jb_quoteleft}

One parcel, comprising 57.99 acres which includes present-day Tribal businesses, including FireLake Discount Foods, was given to the Citizen Potawatomi Nation by the Secretary of the Interior in September 1960. The larger parcel of land supposedly annexed by this same ordinance was the 194 acres that included the land and structures that were part of the Shawnee Indian Sanatorium. This larger parcel was controlled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs until it was divided between the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and the Absentee Shawnee Tribe in 1963.

Because the land was owned by the Federal Government and the tribes, Federal law required the signature and authority of the Secretary of Interior before it was sold. The City of Shawnee never determined who owned the land and never requested permission of the Secretary of the Interior before their rushed annexation.

Tribal resolutions and minutes from Citizen Potawatomi Business Committee meetings suggest that members of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation believed that the federal government, specifically the United States Public Health Service, still owned the land in 1962.

A representative from the Bureau of Indian Affairs attended the April 1962 meeting of the CPN Business Committee where the issue was discussed, confirming that the Tribe believed the land was still in control of the United States Government. Although the City of Shawnee claims that this same land was annexed into the City of Shawnee in 1961, the land owners were never advised and the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and Absentee Shawnee Tribe continued their plans to use their land for the economic benefit of the tribes.

In the early 1980s, the Citizen Potawatomi Nation began bingo and golf enterprises. In 1984, it created a tax commission and opened smoke shops. In 1988, Congress passed the Self-Governance Act and National Indian Gaming Act. For the first time in centuries, Native American tribes were finally allowed to govern themselves and pave their own way toward economic self-sufficiency.

In 1988 FireLake Casino opened for business and CPN purchased First National Bank, a Shawnee-based financial institution. Throughout the 1990s, the Tribe continued to flourish. New programs and enterprises were added to CPN’s portfolio and agreements for the Tribe to manage its own affairs were signed with the United States Indian Health Services and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

In 2001 Citizen Potawatomi Nation opened one of its largest enterprises, FireLake Discount Foods. The grocery store serves as one of the only grocery stores in rural Pottawatomie County and also provides a larger tax base so that Citizen Potawatomi Nation could expand the programs and services for Tribal members and community members.

Throughout the 2000s CPN continued to diversify rapidly, adding new businesses and creating jobs. The Tribe opened FireLake Grand Casino, expanded the locations of First National Bank, opened a bowling center and ball fields. To serve its growing number of members, CPN created the first “virtual legislature” so that the eight legislative districts across the United States and the eight legislative districts in Oklahoma could meet via simulcast.

This economic development created a significant impact in the local communities. CPN created 7 out of every 10 jobs in Shawnee, Okla. during that time and by 2012 CPN’s total economic impact had grown to more than $522 million in 2012 alone.

Yet during this time of growth and prosperity, the Citizen Potawatomi Nation had never received notice that its land had been illegally annexed in 1961.

In February 2014, City of Shawnee, Okla. officials demanded that four local Native American tribes begin paying a three percent city sales tax on goods sold to non-tribal members. Of those tribes, the Citizen Potawatomi Nation has the largest retail operation with FireLake Discount Foods. The City blames the Tribes’ economic development for decreasing tax revenue.{jb_quoteleft}Stances like this from City Commissioners come as no surprise given the rhetoric and disregard for tribal sovereignty expressed during the meeting. One city official pointedly asked tribal government representatives if they “believed in one Nation under God.” Another casually asserted that the grocery sales tax was the only issue that mattered to the City, telling tribal representatives that “We’re not interested in the profits from your beads, art work and moccasins from your gift shops.”{/jb_quoteleft}

Since that time a series of letters and data has been exchanged between tribal and city officials. On March 24, officials from the Sac and Fox Nation, Absentee Shawnee Tribe, Kickapoo Tribe and Citizen Potawatomi Nation met with City of Shawnee officials at the CPN Cultural Heritage Center. Despite numerous attempts to point out the illegality in the City’s 1961 annexation during the meeting, officials from Shawnee, Okla. paid little regard to the issue.

A letter from City Commissioner James Harrod states that the City believes “the [annexation] ordinances are presumed valid at this late date.”

Stances like this from City Commissioners come as no surprise given the rhetoric and disregard for tribal sovereignty expressed during the meeting. One city official pointedly asked tribal government representatives if they “believed in one Nation under God.”

Another casually asserted that the grocery sales tax was the only issue that mattered to the City, telling tribal representatives that “We’re not interested in the profits from your beads, art work and moccasins from your gift shops.”

The current City of Shawnee government can’t be blamed for the hasty actions of an administration from five decades ago. What they can do, however, is respect the sovereign authority of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and other tribes which border the City.

The facts in this case are simple; Citizen Potawatomi Nation is a sovereign nation with the authority to assess and collect taxes. A municipality cannot annex land from the United States government or without the consent of three-quarter consent of land owners. This is especially relevant given that the land where CPN enterprises operate is currently held in trust for the Tribe by the federal government. Therefore, the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and its enterprises are not located within the City of Shawnee and are exempt from taxation by any state or city municipality.