By the end of the 1860s, most officials in the United States Office of Indian Affairs realized that their social experiment of assimilation through private land ownership and U.S. citizenship was largely a failure among the Citizen Potawatomi living in Kansas. A small percentage of the Citizen Potawatomi succeeded as independent farmers and businessmen and thrived in the conditions established for them by the allotment and citizenship treaty of 1861.

By the end of the 1860s, most officials in the United States Office of Indian Affairs realized that their social experiment of assimilation through private land ownership and U.S. citizenship was largely a failure among the Citizen Potawatomi living in Kansas. A small percentage of the Citizen Potawatomi succeeded as independent farmers and businessmen and thrived in the conditions established for them by the allotment and citizenship treaty of 1861.

Far more, however, were quickly engulfed by adverse conditions and outside pressures from non-Indian settlers and corporate interests who desired their land and wanted them out of Kansas. When only a few Citizen Potawatomi managed to succeed, federal officials blamed the Potawatomi’s inherent “Indianness” for those who failed to make the transition to agriculturalists.

Such rationalization made it easy to ignore the mismanagement of the assimilation effort by the federal government and the onslaught of corporations and non-Indian settlers pushing for access to Citizen Potawatomi land. The forlorn Citizen Potawatomi who ended up in a general state of landlessness, despair, and poverty refused to succumb to their circumstances however.

Instead, they chose to avail themselves of an “escape clause” in the 1861 allotment and citizenship treaty that allowed them to sell their lands in Kansas and buy a new reservation in Indian Territory.

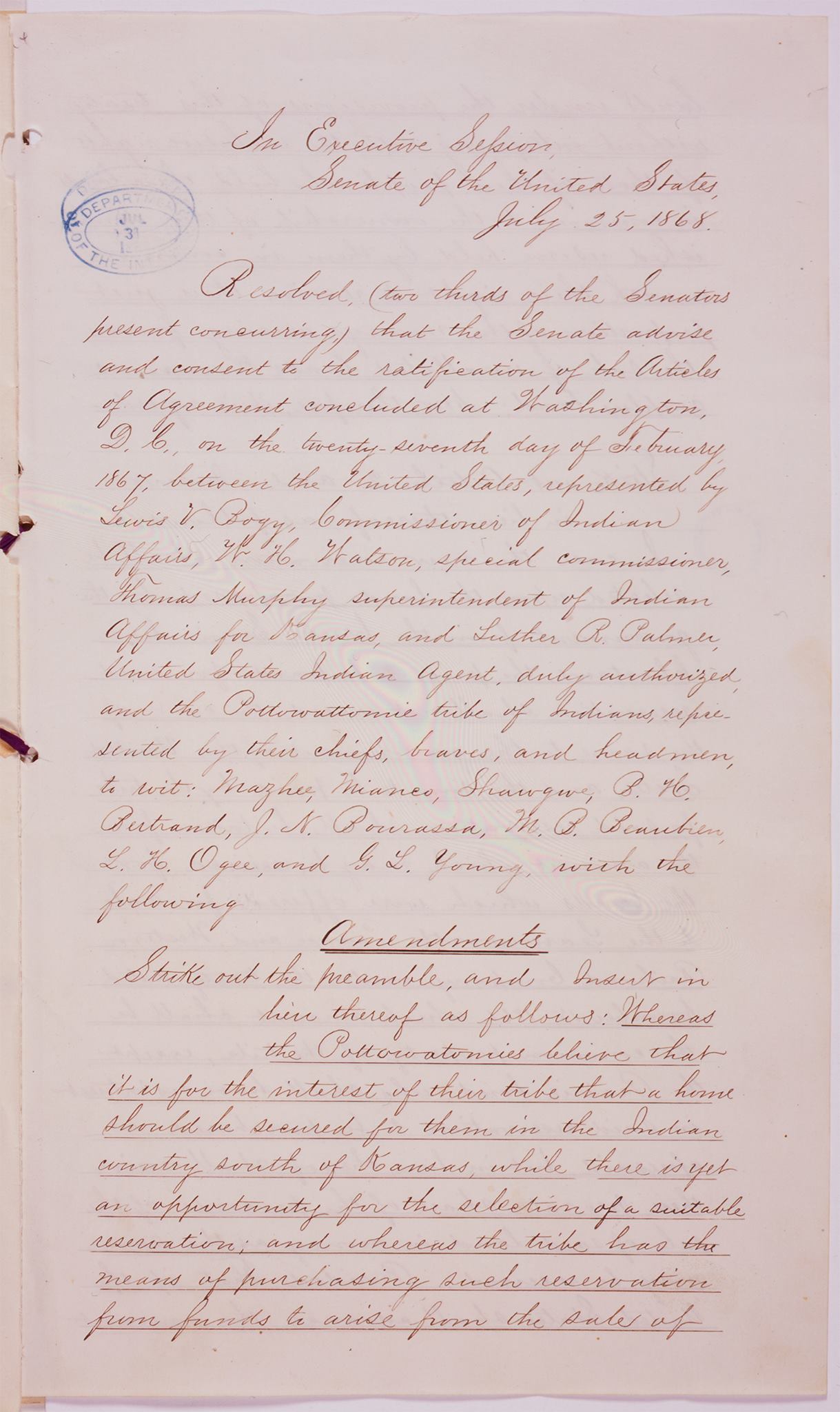

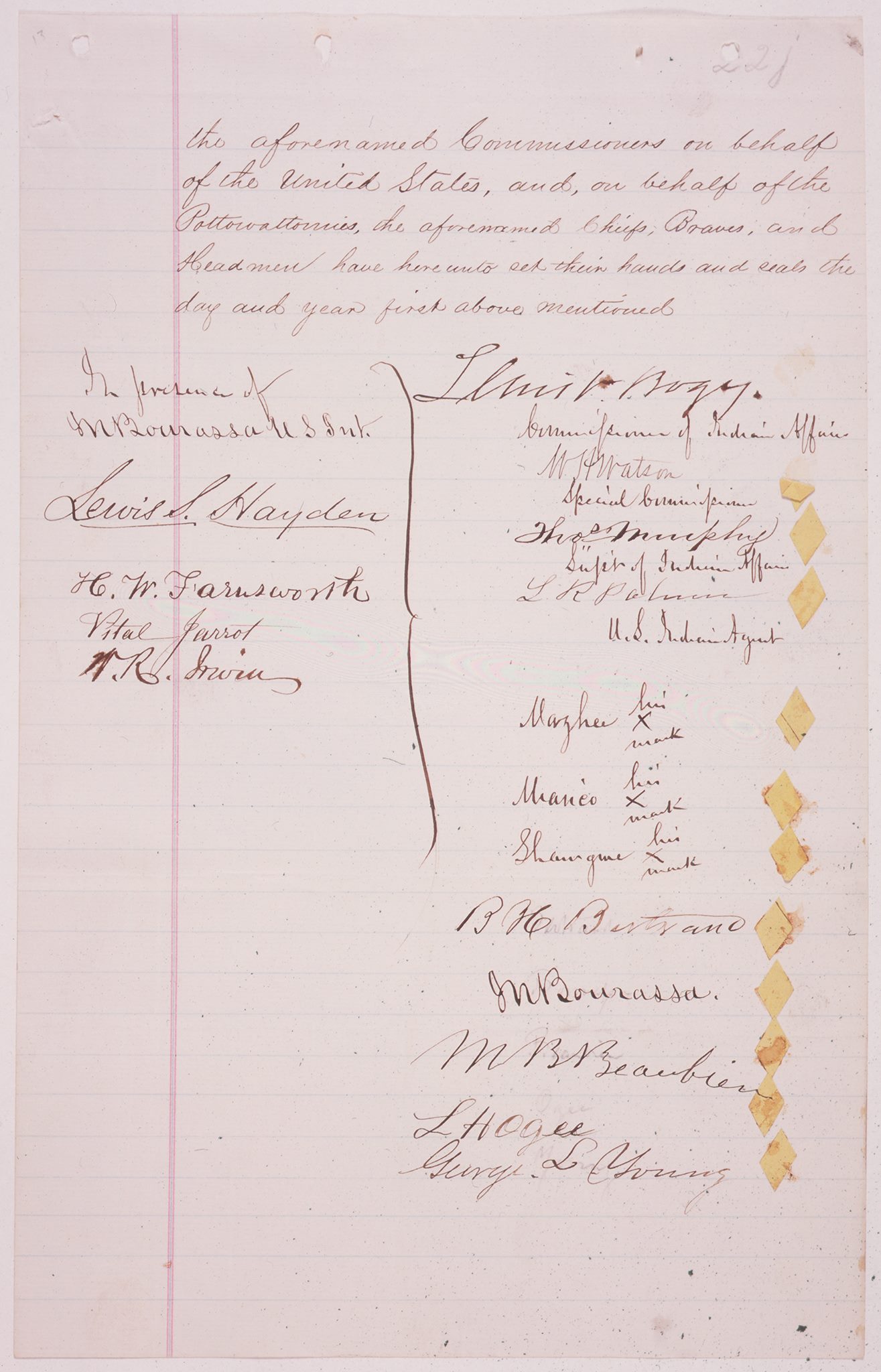

The provisions for the Citizen Potawatomi’s move to Indian Territory were stipulated in a treaty signed on February 27, 1867. In the two years following the treaty, the Potawatomi Indian agent, with the assistance of the Tribal Business Committee, was obligated to create a census of those who planned to sell their private lands and move to Indian Territory and those who wanted to stay in Kansas and become U.S. citizens.

There was no mass exodus of Citizen Potawatomi from Kansas. Unlike previous removals the Potawatomi endured in the 1830s and 1840s, the 1867 treaty agreement did not fund the relocation to Indian Territory. Many of the families were too poor to finance such a move and did not receive the same annuity monies as other Native Americans. The reality was that the poverty that made life on the Kansas reservation difficult also prevented most Citizen Potawatomi from moving to their new reservation in Indian Territory to start over.

The Citizen Potawatomi were not sure when they would move, but with the knowledge that their time in Kansas was limited, most of these individuals did not attempt to put crops in the ground or further improve their living conditions. Those who had already lost their land were largely living in temporary homes on the Prairie Band Potawatomi’s reservation or on the property of their extended family until they could procure the funds to make the move. All were in a state of limbo and growing restless.

In the winter 1869, a party of Citizen Potawatomi traveled to Indian Territory and selected a tract of land that became the site of the Citizen Potawatomi reservation. They chose a section of land that encompassed thirty square miles, or 576,000 acres from the north fork of the Canadian River to the south fork.

In the winter 1869, a party of Citizen Potawatomi traveled to Indian Territory and selected a tract of land that became the site of the Citizen Potawatomi reservation. They chose a section of land that encompassed thirty square miles, or 576,000 acres from the north fork of the Canadian River to the south fork.

Today that territory encompasses Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma. The earliest families to make the journey to their new reserve arrived in Indian Territory in 1872. Since they paid for the move themselves, these families were among the more affluent Potawatomi families who were able to move from Kansas and included members of the Anderson, Melot, Clardy, Pettifer, Bergeron, and Toupin families. Fourteen wagons filled with supplies and eager, yet anxious, Citizen Potawatomi set out for their new homes in Indian Territory with little idea about what they would encounter and how they would succeed in these earliest arrivals settled together in a small community they called Pleasant Prairie near the center of the reservation. By the end of the year the population of the budding community was a mere twenty-eight people.

When the straggling groups of Citizen Potawatomi left Kansas for their new reservation in Indian Territory, none knew what to expect. These individuals, along with their parents and grandparents, were told on several previous occasions that once they moved just a little farther away from non-Indian society they would be left to themselves on land that would belong to them forever.

These promises always proved false. So, the Citizen Potawatomi understood that their lives in Indian Territory were not going to be without trials and tribulations. None of them, however, could have anticipated the decades-long battles they would have to wage to see the rights to which they were entitled realized.