This January, after years of planning and reconstruction, the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center held its official grand reopening, revealing 11 new exhibits. The first explains one of the Tribe’s oral traditions, the Seven Fires Prophecy.

“Our oral traditions are our history,” said CPN Cultural Heritage Center Director Kelli Mosteller, Ph.D. “Before written word, this was how we passed our history down.”

More than 1,000 years ago, a larger group of Algonquin-speaking people known as the Neshnabek included the Potawatomi. Eventually, the Neshnabek divided into the Potawatomi, Odawa and Ojibwe Tribes, becoming the Three Fires Council, with each Tribe having specific duties. The Ojibwe, or oldest brother, are the keepers of trade; the Odawa, or middle brother, are the keepers of medicine; and the Potawatomi, the youngest brother, are the keepers of the fire.

“The Neshnabek were visited by seven prophets,” explained Jennifer Randell, artist and CPN Eagle Aviary director. “Each prophet spoke of a fire — a prophecy or an era that they would endure. Each fire drastically changed their way of life.”

Before coming to work for CPN, Randell studied art at the University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma in Chickasha. She used her training to help sketch and create artwork for the Seven Fires exhibit.

“The prophecies really tell us who we were in the past, where we came from and the struggles our ancestors endured,” Randell said. “They also tell us who we are in the present and what we will be in the future.”

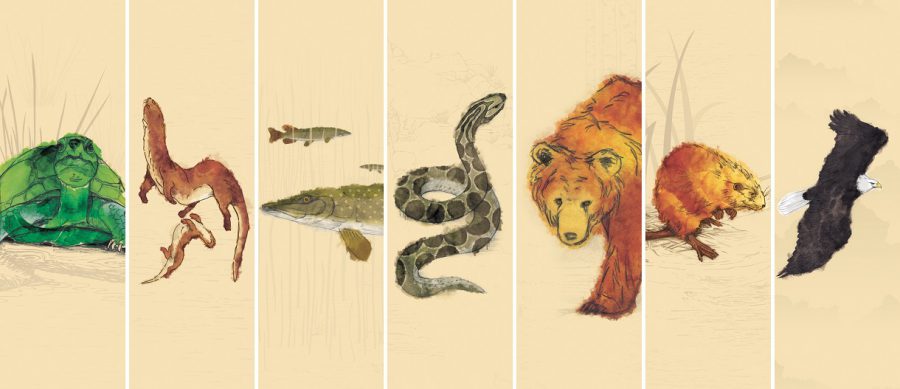

The first prophecy, or first fire, urged the Neshnabek to leave their home and move west following the sacred Megis shell until they reached the land where food grows on water. Otherwise, they would be destroyed. Many Native American groups refer to North America as Turtle Island. Because of this, a turtle represents this journey.

While traveling west, the Neshnabek stopped along the way, eventually reaching a large body of water. In the second fire, depicted by two otters, the Neshnabek people were without direction until the birth of a boy who showed them the correct path.

“We are trying to evoke childhood, and otters, of course, are so playful, it captures that childhood feeling,” Mosteller said.

The Potawatomi eventually arrived in the Great Lakes region, where they found wild rice growing on the water. This fulfilled the first prophecy, and the people knew they had reached the land meant for them.

“The pike makes the wild rice beds their home, and it protects them,” Mosteller said of the carnivorous fish. “It’s where they lay their eggs, and that for us was the same thing the Great Lakes was going to be. … In (this) fire, it’s saying that we would know that we were in the place that we were supposed to be where food grew on water.”

The fourth fire, represented by an eastern massasauga rattlesnake, foretold the Neshnabek confronting a light-skinned race. The prophet said this race would have the face of a friend or a foe, but they would have trouble differentiating between the two.

“The snake that we chose is a species that is the only venomous snake that is indigenous to Michigan,” Mosteller said. “I think people in a modern context with a Christian outlook understand what a snake symbolizes.

“We wanted to have that immediate symbolism that when you look at that and you’re talking about the face of a friend or the face of a foe, we know how this turned out.”

The fifth prophet foretold a time of much hardship for the Neshnabek. The loss of old teachings, an abandonment of traditions and an acceptance of false truths caused long-term negative consequences still evident today.

“In the fifth fire, we’re talking about a time when colonization is happening,” Mosteller said. “Europeans have arrived. There’s starting to be a lot of disjointedness. … The bear is a clan animal, but it is the healing clan. The bear represents the sacrifices made by the Potawatomi people to keep whole, healthy and together as a community.”

The deception of false promises continued in the sixth fire. Many children did not learn traditional teachings, causing the near extinction of Neshnabek culture and history. In the Potawatomi oral tradition of the flood, a single muskrat sacrificed himself to save humankind and animals.

“Muskrats have this deeper connection to them of self-sacrifice for your community,” Mosteller explained. “In the sixth fire, we’re talking about those elders who are weeping for the fact that we’re losing our traditions, and the children are being taken away to boarding schools.”

The seventh prophet told of a generation when the Neshnabek language, teachings and culture experienced revival. Today, most believe we are in the Seventh Fire, and eagles are sacred to the Potawatomi because of the promise and hope they signify.

“We are still here. We’re going to soar high,” Mosteller said. “We’re going to still do the things we need to do, and there’s almost that triumphant rekindling of that Seventh Fire to go back along the path of the ancestors. … These are teachings are lessons that our ancestors passed down to us intentionally because they knew that we would need these ways to guide us.

“You’ll see the animals throughout (the Cultural Heritage Center) so that you can refer back to what was all foretold. This was not just happenstance,” she added. “We knew that these challenges would be faced. Our teachings and our cultural traditions will carry us through, and in the end, we will see a better day.”