It’s a Monday morning like any other. As the third-period tardy bell rings at Wanette High School in Oklahoma, five students casually enter the classroom, grab tablets and take seats next to each other at the round table with their teacher Crystal Caldwell.

The teenagers comprise the only class in the only school district in Oklahoma where Potawatomi is offered as a language credit. Silvia McNeely, Wanette Public Schools principal and superintendent, approached Citizen Potawatomi Nation this spring about creating it.

McNeely said she wanted to bridge the cultural gap between Native and non-native students.

“I also needed to provide more opportunities for the kids to have credits and, of course, one of the state credits is a foreign language,” she said.

In fact, Potawatomi is the only foreign-language credit available in the small, rural district where graduating classes are fewer than 20 people. Otherwise, students can take technology or accounting classes.

CPN Language Director Justin Neely created the curriculum, obtained special licenses and teaches the course, which launched with the fall semester.

“The Department of Education in Oklahoma has been pretty good toward tribes when they want to introduce their languages school districts within their jurisdiction,” Neely said. He has a bachelor’s degree in education, and recently earned his teaching certificate. “The tribe also had to certify me to teach the language. Now, we can offer it anywhere in the state.”

The online program allows students to complete chapters at their own pace. Neely tracks their progress online but also attends classes with them in person once or twice a month. Crystal Caldwell supervises the course.

The online program allows students to complete chapters at their own pace. Neely tracks their progress online but also attends classes with them in person once or twice a month. Crystal Caldwell supervises the course.

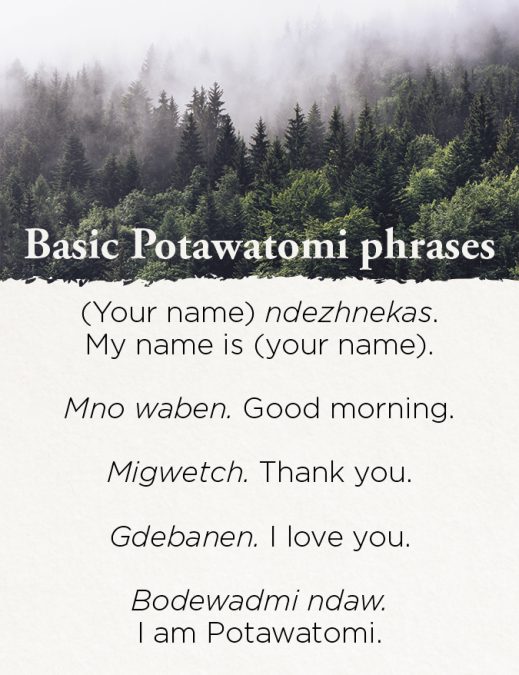

“[It] just has a natural flow to it,” Neely explained. “The first chapter is introductions, then it is animals and then colors. After that, they start learning a little bit more about the verbal structure, like how to construct sentences.”

Crossword puzzles and other word games also reinforce vocabulary retention, as do chapter quizzes and tests.

Another constructive aspect has nothing to do with language, but rather preparing students to continue learning after high school. Working on tablets and accessing their course materials online reflects a secondary educational experience.

“The kids that are going into college and the kids that are going into vocational school, they’re getting into a lot of blended classes with technology,” McNeely said. “So this is a great introduction. … Personally, [my own children] had a tough time with that, taking those blended classes in college, because they hadn’t really done that in school.”

Potawatomi language students are upperclassmen. None of them are Citizen Potawatomi, and some didn’t know the language existed before they enrolled.

The students take the challenges as they come.

“I just got put in this class. It’s pretty fun, if you ask me,” said student Brian Ashley. “It’s good to learn new things with language.”

He said he looks forward to speaking complete sentences and teaching them to his family.

Neely hopes to offer the program as a language-credit course to high schools across the country.

“If Potawatomi can fill that void where you can take two years of Potawatomi instead of taking two years of French, what an awesome thing to have our kids be able to take their own language, engage in their own language, learn their own language,” he said.

Globally, there are fewer than 10 first-language Potawatomi speakers and fewer than 50 fluent second-language speakers, which Neely described as “kind of a crisis period” for the survival of tribal culture and communication.

He hopes teaching Potawatomi in public schools and online via CPN’s website will encourage more tribal members to carry on its oral traditions.

But for right now, Ashley and his Potawatomi language classmates will keep laughing together as they learn phrases like “Whatever,” “Leave me alone” and “I love you,” and then shout them at each other in the halls.

For more information on the Potawatomi language, visit potawatomi.org/language.