In 1634, French explorer Jean Nicolet made initial European contact with the Potawatomi near Green Bay, Wisconsin. The fourth section of the Cultural Heritage Center introduces the coming together of two worlds.

“The goal was to tell the complete story of how this pivotal period impacted the Potawatomi, their French allies and the future landscape of an American continent. Contact between these two cultures resulted from the Potawatomi fleeing the eastern Great Lakes as the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and their allies, armed with British weapons, pushed west with violent raids,” said Blake Norton, CHC curator.

The CHC partnered with Bluestem Integrated, LLC from Tulsa, Oklahoma, to print and install the images featured in this section.

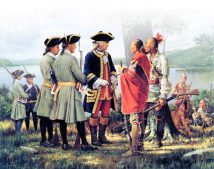

“The murals in this gallery are beautiful works of art that detail events during this time. They really provide an inside look,” he said. “Trade and social interactions between Natives and colonials are portrayed so effectively in each painting as well as the goods being exchanged.”

European-Native convergence

The first display within this section showcases Potawatomi designs, tools and weapons as a result of early commerce with Europe including intricate silver work created by CPN tribal member Bill Madole.

“Being a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, I’ve always been interested in the heritage of our Tribe,” Madole said. “One of the items that the Potawatomi wore was jewelry, in particular, silver — what is called trade silver. That name came about because the Potawatomi and the other Indians, after European contact was made, began trading pieces of silver.”

Madole is from the Anderson family, and as his interest in the Tribe grew, he began researching early Potawatomi jewelry.

“There are different photographs from museums and pieces that are still available, and so I took the inspiration from those photographs and tried to make pieces that were historically accurate,” he said.

This section features two silver conches Madole hand crafted.

“I am honored that my pieces are in such a beautiful place and beautiful setting,” he said. “I can’t say enough about the Cultural Heritage Center.”

Madole began working with metal more than 30 years ago to keep his family’s forging tradition alive.

“My great-grandfather John Anderson was a blacksmith,” Madole said. “It was a very big operation, and he had an anvil that was passed down to my grandfather, who passed it down to my father, and my father then passed it down to me.

“I still use the anvil every day,” he said. “It’s almost been in continuous use since well over 100 years or so.”

While European contact brought deadly diseases and a wave of change, it also introduced new, stronger tools. Before contact, the Potawatomi cooked by using clay pots, animal hides and other natural sources. The European’s iron kettles lasted much longer than original cookware.

The display also features other items the Potawatomi obtained via contact including a violin and several books. However, consequences of colonial influence quickly impacted the Potawatomi and all the Native groups in the Great Lakes region.

Iroquois Confederacy

Prior to Jean Nicolet’s journey to the Great Lakes, the Dutch made contact with Iroquois on the eastern shores of the continent in the early 1600s. New, European resources gave the Iroquois the ability to quickly and easily garnish influence over other Native groups. They conducted occupational raids and campaigns, invading the area in which the Potawatomi lived. Since the Iroquois were some of the first Native Americans to obtain firearms from the Europeans, they succeeded.

The Iroquois began moving west into the central Lakes, pushing out interior tribes that did not have equal footing, he said.

“There is evidence to show that people fled north along the eastern shores of Lake Michigan,” Norton said. “When they reached the Straits of Mackinac, the Potawatomi crossed over into northern Wisconsin, continuing south and settling at what would become Green Bay and Milwaukee.”

As a result, many of the cities in northern Wisconsin bear Potawatomi names. However, movement into Wisconsin displaced the region’s other Native groups.

“Native Wisconsin tribes began being displaced, creating tension and conflicts with the eastern refugees,” Norton said. “Other refugee tribes who found safe harbor in Wisconsin were the Miami, Kickapoo, Sauk and Meskwaki or Fox.”

Because of the vast number of displaced Natives, large refugee settlements began forming.

“From written and oral accounts, the Potawatomi were the more dominant people in the area,” Norton said. “They had an integral part in building and protecting these large trading hubs.”

Middle Ground

Eventually, the French and other colonists began making their way down the St. Lawrence River into the interior of the Great Lakes region.

“The large trading centers of Wisconsin enticed explorers, traders and missionaries to venture into the Great Lake’s interior, creating what would become the Western Fur Trade,” he said.

As the fur business grew, the Potawatomi and French had a balance of powers for a time, or Middle Ground.

The French relied on their Native allies including the Potawatomi to teach them hunting techniques, form relationships with other tribes and gain influence around the Great Lakes.

Trade “is what made or motivated people to interact with each other, which eventually led to intermarriage and the Métis families that we see today,” Norton said.

For a time, the Potawatomi and French both experienced success. However, greed and resource depletion proved troubling.

“Feeling exploited, the Potawatomi’s relationship with the French began to sour. The French were taking advantage of their allies,” Norton said.

Many countries and businesses looked to make money in North America, which eventually resulted in the Beaver Wars, Fox Wars and the French and Indian War.

“It really started to disrupt this very, very valuable fur trade,” he said.

Continued European influx and the negative repercussions of disease and European influence on the Native American population caused the Middle Ground’s dissolution.

Beaver Wars

Potawatomi and others exchanged with the French to obtain firearms and began raids against enemy forces during the Beaver Wars, which lasted from 1628

to 1701.

As the Potawatomi kept pushing east, “the French followed, wanting to stick close to their valuable and protective allies. They understood that the Iroquois were defeated and peace would soon be made, opening up the lower lakes for reoccupation,” Norton said.

“Some of the most violent conflicts that were ever fought on this continent were part of the Beaver Wars,” he said.

In 1701, New France and 1,300 delegates from 39 Native American nations signed the Great Peace of Montreal, ending decades of fighting. The Iroquois stopped their campaigns against other Native Americans in the Great Lakes region and allowed tribes to return to their original lands.

“It’s not coincidental that after that peace treaty was signed that Fort Detroit was then established,” he said.

At this time, the Potawatomi took the opportunity to stake claim over the area, and Fort Detroit served as an eastern defensive stronghold for France and its allies.

“Being centrally located between the western and lower Lakes, New France and eastern territories, and at the axis of several key waterways, Detroit was a prime spot,” he said. “It was sought after by colonial powers, so it changed hands several times during periods of war.”

While this treaty attempted to end the battle for control, the fur business proved too lucrative for peace. The Iroquois Confederacy, French, Dutch, English and American Indians continued to fight for land and rights to its bountiful resources.

Fox Wars

Strife between the British and French and their respective Native allies continued. The British joined forces with the Meskwaki (Fox), which caused the French to form a campaign against the Meskwaki. Confrontations between the two groups ensued between 1712and 1730.

Records indicate by 1733, the few remaining Meskwaki sought refuge with the Sauk.

Métis influence

“What defines this time other than warfare was the coming together of two worlds,” he said. The paintings in this section highlight this conversion and serves as a visual reference for this point in history.

“Intermarriages occurred between regional traders and the family of prominent headmen,” he said. “These unions created kindred and corporate bonds.”

The section spotlights early Potawatomi leaders including Chief Topinabee, Chief Leopold Pokagon, Madeline (Bourassa) Bertrand and Joseph Bertrand.

Joseph and Madeline Bertrand’s influence in the area is evident today. Parc Aux Vaches-Madeline Bertrand Park in Berrien County, Michigan, sits near the St. Joseph River and Lake Michigan, where Madeline and Joseph once established a profitable fur-trading post.

“Madeline and Joseph ran the trading post together,” he said. “Between her family and cultural ties and him being a business savvy trader, it worked to their benefit.”

The intermarriage and the coming together of two different cultures became a defining moment for the Potawatomi and the continent. This section of the museum serves as an educational opportunity, introducing some of the first Potawatomi Métis families and features an interactive map detailing where they lived.

“Our Tribal members are interested in the interactive because they see their family names,” Norton said. “A lot of people really don’t know how deep that history goes back and how important a lot of these people were in history. These traders — these are the founders of major cities, Chicago being one of them.

“People can start understanding that these connections are more like a spider web than a family tree,” he said. “Many of our families are very closely related.”

French and Indian War

Conflict between the Europeans and Native Americans persisted.

“Foreign alliances and the fur trade unbalanced intertribal relationships in the Great Lakes,” Norton said. Tribes prospered, while others wanted more. Traditional enemies became business partners and allies into rivals. War soon followed.”

The French and their allies began converging at different spots to parlay or fight against the British, initiating the French and Indian War which lasted from 1754-1763.

At the end of section four, an image of the Battle of the Monongahela wraps along the wall. Stories recount a Potawatomi warrior dreamed and foresaw this conflict that occurred on

July 9, 1755.

“From that dream, they used it as a battle plan,” Norton said. “They ambushed the British column, killing Major General Edward Braddock and defeating a young Virginia colonel

named George Washington. It was a devastating loss for the British at the start of the war.”

The fighting occurred near present-day Braddock, Pennsylvania. CHC visitors can find George Washington wearing a blue coat in the image.

CHC staff chose this painting as a focal point. It highlights the Potawatomi’s strength, agility and reputation as leaders, traders and warriors during this time. These qualities played a major role following the French and Indian War as the Potawatomi would face more wars to come.