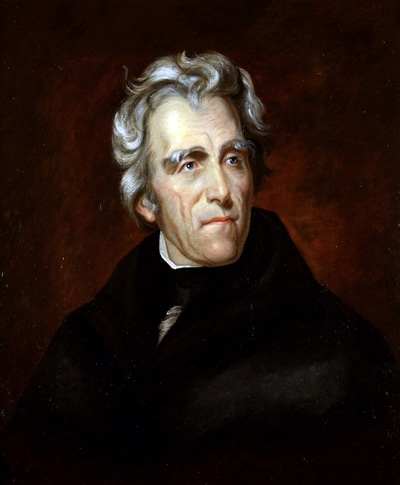

As the president who signed the Indian Removal Act, Andrew Jackson is not an idolized figure in Indian Country. First a frontier Indian fighter against the Creeks, then as an American president who ignored a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in favor of the Cherokee Nation in Worcester v. Georgia, there is little endearment for the nation’s seventh president especially amongst Oklahoma’s tribes.

In recent years, Jackson’s place on the U.S. $20 bill has become almost as controversial as his legacy. Now, one Oklahoma senator is calling on the U.S. Treasury Department to remove the former president known as “Old Hickory” from the note permanently. In response to the Obama Administration’s 2015 announcement that the treasury would begin consultations on replacing Alexander Hamilton’s likeness on the $10 bill, Oklahoma Senator James Lankford (R-OK) introduced a resolution supporting Jackson’s removal from the nation’s currency.

“The administration has already announced they will place a woman on the $10 bill in 2020,” said Lankford. “I support recognition of a historic American woman on the twenty-dollar bill and the removal of Andrew Jackson, since he began the Indian removal policies that forced thousands of American Indians off their ancestral homelands.”

According to Lankford’s spokeswoman Aly Beley, the resolution has been referred to the Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee and is awaiting consideration. The resolution is the first action from policy makers concerning the treasury’s consultations on changing likeness on the nation’s currency since the treasury’s announcement. Critics of the former president have long called for his removal from the bills, though some have countered that the growing critiques of Jackson stem from a recent rise in left-leaning academia and misunderstandings of historical fact.

In a June 2015 op-ed on www.politico.com, Professor David Greenberg of Rutgers University said critics of Jackson’s legacy “represent the overripe fruit of two generations of anti-Jackson scholarship.” Greenberg cited historians like Charles Beard, Arthur M. Schlesinger and “1970s New Left historians such as Michael Paul Rogin, awakening to problems his predecessors had ignored, placed Indian removal at the core of Jackson’s legacy and racism at the heart of his vision.”

Lankford’s office contends that while it can acknowledge Jackson’s role in American history, such an acknowledgement does not have to equal a place of honor on one of the nation’s most potent symbols; its currency.

“As the Treasury Department is currently seeking public comment to remove Alexander Hamilton and place a woman on the $10 bill, the resolution was introduced to recognize the many aspects of American history impacted by President Andrew Jackson,” wrote Beley. “Although he did have good policies as president and was a hero during the War of 1812, his Indian removal policies that led to the forced migration of Indians from the southern states to what is now Oklahoma were abhorrent. Although no tribe officially approached the senator’s office to request the resolution, the removal would allow Native Americans to use American currency without a constant reminder of their ancestor’s plight.”

Jackson originally featured on the $20 bill in 1928, after the bill’s previous face, President Grover Cleveland, was moved to the $1,000 bill to replace…Alexander Hamilton. Jackson’s likeness on the notes issued by the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank seems sardonic when considering his dissolution of the Fed’s forerunner, the Second Bank of the United States, through presidential veto in 1828. The Tennessee-native was deeply mistrustful of moneyed interests, best exemplified in the Bank of the United States and it’s notes which represented the interests of “money power” over common Americans at the time. The fact that the same individual who so detested paper money now risks having his likeness struck off those same bills is not without irony.