Submitted by Jennifer Randell and Bree Dunham

Wadasé Zhabwé, originally named Penojés, was one of the first eight eagles to call the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Eagle Aviary home in 2012. Who could have imagined the future the Creator had in store for this young eagle and the records she soon would set?

“April 16, 2018, marks five years since her release, and I am amazed that we still have the opportunity to follow her progress,” said CPN Eagle Aviary Director Jennifer Randell. “It is still exciting to track her movement across Oklahoma. To be a part of her journey is humbling, and it is an honor for us to continue to share her story.”

That story began when Wadasé Zhabwé fell out of her nest in Florida in 2012. A Good Samaritan rescued her and took her to the Audubon Center for Birds of Prey in Maitland, Florida, for treatment. The fall from the nest fractured her left wrist, or wingtip. There was evidence something may have attacked her on the ground, further damaging the already injured wing. According to the paperwork the CPN Eagle Aviary received when she arrived, she would never fly well enough to be considered for release. Veterinarians and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service deemed her non-releasable.

“Originally we intended for her to be one of our education birds, to train on the glove,” Randell said.

However, as the birds went through their vaccination regimen, Randell and CPN Eagle Aviary Assistant Director Bree Dunham noted some encouraging improvements.

“We noticed that her feathers started coming back, which was encouraging,” Dunham said. “But in addition to that, the fracture had healed well, and her wing had a normal range of motion. That was an excellent sign.”

As time passed, Penojés began to fly inside the 150-feet-long, half-round aviary enclosure, performing figure eight maneuvers above the other eagles. It became clear that the wing injuries healed much better than expected and that Penojés should be released. Randell and Dunham reached out to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and asked permission to release her, but there was a hitch in the plan. Due to her non-releasable status, USFWS was not initially supportive of the release.

“We explained that is our belief that these eagles are our messengers and carry our prayers to the Creator,” Randell said. “If for any reason we could get them back out into the wild, that’s what we must do.”

Ultimately, USFWS agreed to the proposal. Randell and Dunham began working Penojés for release. She was long-lined and conditioned to reach her ideal flight weight and strength. She learned to catch live prey and further demonstrated her ability to survive in the wild on her own. During this time, the aviary staff also proposed that Penojés be soft released at the aviary and fitted with GPS telemetry to allow them to monitor her progress and study her movements once in the wild. Having been born in Florida, most raptor experts believed that even if she was released in Oklahoma, a state where she grew up, she might travel back to the Sunshine State. The release was set for spring 2013.

There was one other small problem though. Penojés means “Child” in Potawatomi, but that name just was not going to cut it for a bird taking her first steps into the world on her own.

“We had to rename her to send her back out into that big world,” Randell said. “It’s rough out there; we wanted her to have a stronger name — a name that told the story of her journey.”

With assistance from Tribal Chairman John “Rocky” Barrett, the CPN Cultural Heritage Center and Language Department, Penojés was reborn as Wadasé Zhabwé.

The new name translates as “Brave Breakthrough” and draws on Wadasé’s ability to go through something difficult and come out stronger on the other side. “It was a perfect name for her,” Randell said.

The day of release, Chairman Barrett held a naming ceremony in the morning, which was the first for any eagle at the CPN Eagle Aviary.

With the assistance of fellow eagle experts from the Raptor View Research Institute and Sia: The Comanche Nation Ethno-Ornithological Initiative, Wadasé was fitted with the telemetry unit before being placed on the aviary meadow’s release platform. Once removing her hood and tethers, Wadasé sat nearly motionless.

“Nothing happened for a few minutes, which seemed like an eternity,” Randell said.

After several minutes of taking in her surroundings, Wadasé took flight across the meadow, eventually landing along the tree line, still visible from the aviary, where she roosted for the evening. She wouldn’t be seen again on the aviary grounds for nearly a month.

The GPS data from Wadasé’s backpack can only be downloaded from the Argos satellite once every three days. With some luck, she was spotted by fellow Tribal employees at the pecan farm and other areas near the aviary those first few days. More than 20 days passed before she made her way back to the aviary. One afternoon, she was spotted under the big pecan tree out front, healthy but hungry. She eagerly made her way to the platform once aviary staff provided a meal.

“Once she returned to the aviary, she came nearly every day for food, but soon it was once a week, then once a month, then we didn’t see her for six months,” Randell said, then thanked the employees at the Nation for going above and beyond in their willingness to work with and near the eagle. She said that those working on construction or maintenance projects did their best to give her time in the early mornings and not startle her so that she would feel safe and secure in the space around the aviary.

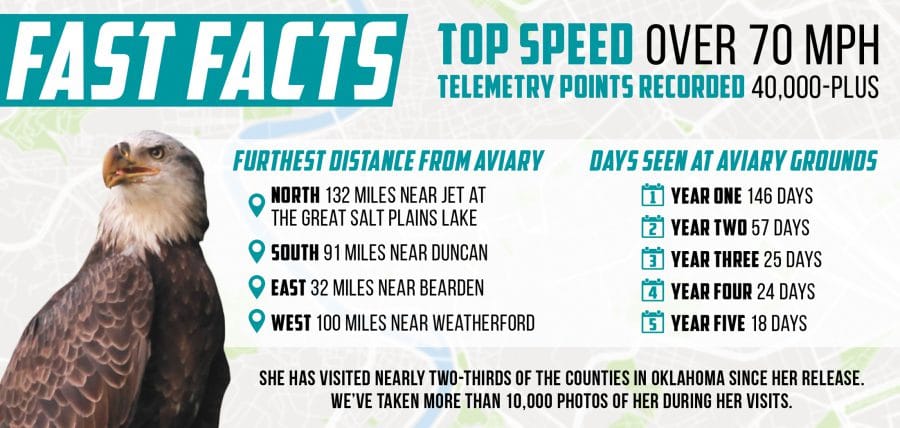

With Wadasé there have been many firsts, including her status as the first bald eagle to be banded and released from a Native American aviary with GPS telemetry. Robert Domenech of Raptor View Research Institute, who fitted Wadasé with the GPS backpack, admitted that day that, while he had experience in placing the packs on many birds, a bald eagle was not one of them. Wadasé was the first. Given eagles tendency to be in and around water, he told Randell he did not expect the backpack to remain on her for more than six months to a year before the cotton stitching would break down and the unit would naturally fall off. Five incredible years later, the pack — roughly the size of a Matchbox car and weighing just 48 grams — has so far remained functional and secure on the young adult Wadasé.

The data gained from the telemetry provides a wealth of knowledge about the patterns and habits of young bald eagles. Many travel hundreds of miles during migration.

“We’re fortunate that Wadasé has generally stayed in a 70-mile radius of the aviary,” Randell said, then laughed. In fact, she has never left the state of Oklahoma.

Although Wadasé has stayed close and has fairly predictable areas she frequents, she started hanging out at Lake Stanley Draper nearby. For an eagle that had mostly spent time near rivers, this was new behavior. Now that she is a fully mature adult, the aviary staff expected her to choose a mate this past fall or early spring and thought a mate may have prompted the change of scenery. However, she has moved on from the area and did not nest this season.

In her fifth year of life in the wild, there are no doubts that Wadasé Zhabwé is thriving. She no longer depends on the aviary for support, but she still visits from time to time. Many people both in and outside the Nation have become avid followers of her progress.

Every third day, Randell and Dunham continue to log on to review the telemetry data in search of her with as much anticipation as they felt on April 16, 2013. The aviary staff is quick to point out, without people coming together, this release would simply not have been possible.

To the good Samaritan and the dedicated staff at the Audubon Center for Birds of Prey, Bill Voelker and Troy of Sia, who assisted with her conditioning and release; Rob Domenech from the Raptor View Research Center, who came all the way from Montana to band and fit her with telemetry; CPN for the support of this program; USFWS for its efforts and partnership; and those close by who have kept an eye out for her and to everyone who follows her journey: “We just want to sincerely thank everyone who made this release not just a possibility but a success,” Dunham said. “She is a blessing to our Tribe. There is no modern record of any tribe having this kind relationship with an eagle.”

In truth, Wadasé could go anywhere she chooses now, and for her to come “home” to visit is nothing short of amazing. If you would like to follow news of Wadasé or learn more about the CPN Eagle Aviary, visit cpn.news/aviary. As always, aviary staff encourages others to keep their eyes out for Wadasé when near the areas she frequents. Send encounters with Wadasé or any other eagles to CPN Aviary staff at aviary@potawatomi.org.